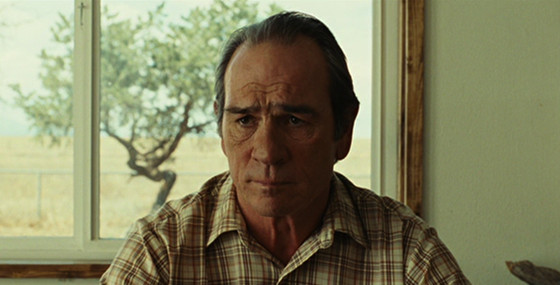

10. No Country for Old Men

Joel and Ethan Coen could have settled for a significantly above average cat-and-mouse thriller with their Best Picture winning No Country For Old Men, but the brothers had something else in mind. Completely abandoning traditional narrative in favour of a philosophical rumination on the nature of masculinity, justice and the nature of violence, the Coens kill off their protagonist, let their antagonist walk away unpunished for his crimes, and end with a recounting of dreams that offers little in way of resolution.

Thematically, the ending allows the filmmakers to wax philosophical and eschew the boundaries of traditional structure, but the final scene upset many viewers expecting their preconceived notions of cinematic justice to be satiated. As the characters become legendary personifications of ideas, audiences are left to make what they will of the film’s ultimate meaning, escalating No Country For Old Men into the realm of timeless cinema.

9. The Graduate

Mike Nichols struck the cultural zeitgeist with his generation defining movie about post-graduate angst and the early years of adulthood. Benjamin Braddock’s affair with Mrs. Robinson remains one of the cinema’s most endearing relationships, fraught with problems as it is. However, it is Benjamin’s romantic attempts to woo Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, Elaine that offers the centrepiece for Nichols’ drama.

Ripe with sexual confusion and questionable romance such as Elaine’s accusation that Benjamin raped her mother and the scandalous mother/daughter/boyfriend conflict, The Graduate ends on one of the most fascinating shots in film. As Benjamin and Elaine elope on a bus, running away from Elaine’s planned marriage, they smile at each other, but soon their smiles fade and they look away, staring into the distance.

Are they happy or sad? Revisits to this film provide nothing but evasive interpretations and lead to no definitive stance. The Graduate has a lot to say about our relationships with each other in our 20s, and about our relationships with ourselves, and it still makes for good debate almost 60 years later.

8. Inception

Christopher Nolan would probably get along very well with French philosopher René Descartes, as Inception explores the possibility that our entire existence is a mere illusion. It is no surprise that this movie about dreams within dreams ends with a giant question mark, dividing audiences over whether or not Cobb is dreaming in the end.

Narratively, the answer to this question is not central to Cobb’s character arc – what matters is that he is no longer obsessed with knowing – and from a structuralist perspective the film accomplishes everything it needs to, but Nolan doesn’t like simple endings and would rather leave us with a twist.

The spinning top allows for repeat viewings to offer multiple fan theories that look for clues in the details Nolan fills his film with. We don’t exactly see the top fall, but we see it wobble just a little bit, suggesting that he isn’t dreaming. On the other hand, there are certain things we know from the earlier in the film – namely that the top might not belong to him at all – that suggest he never woke up in the end, or maybe he’s been dreaming the entire time.

7. Barton Fink

Barton Fink is about writer’s block in the best way that a movie can be about the writing process. Barton Fink is a writer who moves to Hollywood to write a boxing movie, a big studio production designed to make a lump sum of money, but he would rather describe himself as a writer for the common man. Staying in one of the most deliriously macabre hotels captured on celluloid next door to a frightening salesman who relegates him with stories of his travels and unsolicited writing advice, Barton Fink cannot actually write anything.

The movie takes a disturbing turn of events with a murder, a police investigation, and a mysterious box Barton’s neighbour gives him. Before Se7en gave us Brad Pitt’s oft-quoted line, “what’s in the box?” Barton Fink asked that question but never gave us an answer at all.

Barton never opens the box, but he carries it with him until the end of the movie. In the final scene, a woman asks him what the box contains. He simply answers that he doesn’t know. It works as a metaphor for life’s mysteries, or as a metaphor for writing, or simply as an unanswered mystery in the film meant to do nothing more than pique our curiosity.

6. The Shining

Stanley Kubrick was a master at getting his audience to feel exactly what he wanted them to while letting them think they had brought their own interpretations to his work. His entire filmography is filled with alternative meanings and countless analyses have been done by critics and fans alike, trying to parse down exactly what his movies meant, but The Shining is one of his most perplexing.

Defying any easy answers, The Shining still scares to this day because of its lack of clear definition. A metaphor for alcoholism, family dysfunction and or violence, Jack Torrence’s descent into madness comes to a famously confusing end with an old photograph of the Overlook Hotel containing Jack in the forefront revealing that the hotel is… nobody’s quite sure.

Is Jack a ghost or is the entire movie an elaborate ruse? The final frames open up a can of worms that resets whatever notion we had about what the movie meant and frightens us to the core with its evasiveness.

5. The 400 Blows

Francois Truffaut almost single-handedly ushered in the French New Wave with his debut film, beginning an era of movies that broke down the barriers of what audiences believed movies were supposed to be about. The 400 Blows remains his most personal, based on his own life, which makes it as impenetrable as it does fascinating. Antoine, our young protagonist, suffers through a life of juvenile delinquency before running away from his problems in one of cinema’s most famous long takes.

As Antoine runs along the beach toward the ocean, he turns and looks directly into the camera and then the frame freezes on his face before fading to black. It is a perfect use of a glance and an editing technique to hammer home the bleak existentialism Truffaut is exploring in his recounting of his youth, as it offers no real catharsis to the story.

Is The 400 Blows a happy ending or a sad one? Does the freeze frame represent freedom or imprisonment? Life or death? Truffaut once remarked that the freeze frame was an accident, that Jean-Pierre Léaud simply didn’t look into the camera for long enough, but the stasis of the freeze frame offers up radically different conclusions for the audience to make if they can’t find closure.

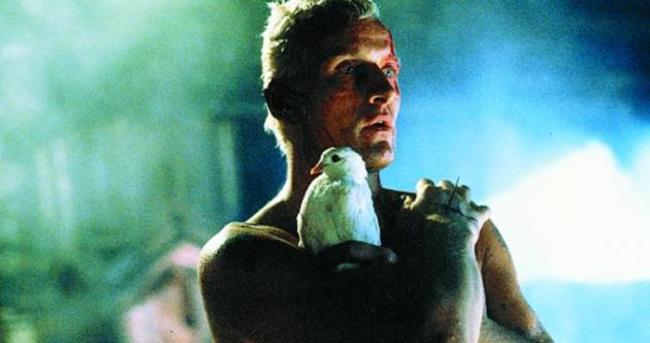

4. Blade Runner

In the future, replicants are bioengineered androids and Rick Deckard is a Blade Runner, a police officer tasked with “retiring” rogue replicants who have gone against their human programmers.

A new model of replicants that are programmed with memories to remove their self-awareness of their lacking humanity are nearly capable of passing the Voight-Kampff test, a test designed to test for human traits such as empathy, making Deckard’s task even more complicated, but when he falls in love with a replicant who truly believes she is human, he must ask himself where his own humanity lies.

Using one of sci-fi’s most endearing questions about the qualities that make us human, Blade Runner presents elegant symbolism and metaphors that question whether or not Deckard is himself a replicant. The ending, featuring a now iconic origami unicorn offers multiple interpretations, inspiring fan theories and cementing Blade Runner as a timeless work of science fiction.

3. La Dolce Vita

Federico Fellini’s masterpiece of Italian cinema is certainly difficult to digest at times but it remains a fascinating story. Following a journalist turned tabloid reporter through what some have interpreted to be seven nights inspired by the seven deadly sins, the movie examines Marcello’s unrelenting boredom with the entertainment and life of the upper class.

After prolonged, at times confusing but never dull sequences, including a bizarre religious ceremony, a seance in a spooky mansion, and a series of sexual debaucheries, the movie ends on a beach where fishermen pull in a dead manta ray. Marcello sees a woman he had met earlier but doesn’t recognize her, or doesn’t care to notice her, and then walks away as the film fades out.

Whether it is a series of random events or a thematic allegory of hell, or something entirely different, La Dolce Vita is a perfect movie for fans of Italian cinema.

2. Rashomon

Akira Kurosawa’s Academy Award winning tale of varying witness accounts of a single crime opens up the door for audiences to choose who they believe and who they don’t. Each viewer may have a different idea of who is telling the truth, or if any of them are, because the movie never shows us what really happened, only the different retellings given.

The “Rashomon effect” is a technique often employed in contemporary movies wherein conflicting accounts are finally pushed aside in the end to reveal the truth, but Rashomon does not do this, and provides insight into unreliable witness and the fallibility of memory.

Now considered one of the most famous movies ever made, Rashomon masterfully juggles each revisit to the same story by supplying details that appear to change the truth but only ever turn out to be another red herring in the difficult path to discern reality.

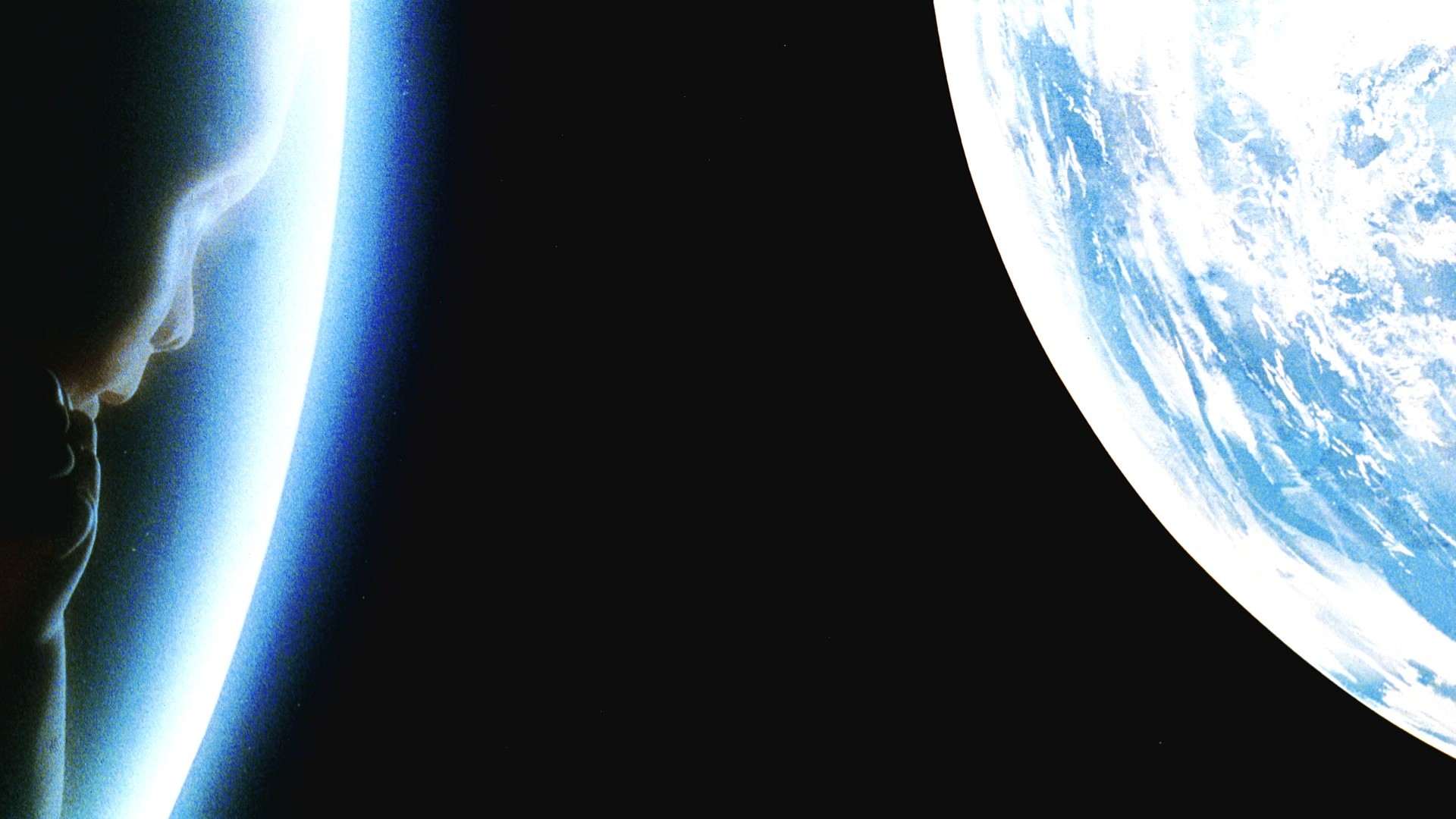

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Ripe with metaphors, allusions and symbolism, Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the most puzzling movies ever made. From the mystery of the monolith to the visually mind-boggling to the cerebrally challenging space baby, Kubrick help up a mirror to his audience, reflecting back whatever they were willing to bring to the film and turning humanity’s eyes back in on itself.

Multiple viewings offer no further clarity as the film defies definition and seems to mean something different every time, but the power of Kubrick’s cinematic space epic has not faded with age. It continues to attract new generations of movie goers to this day, begging for but refuting countless analyses, conspiracies and interpretations.

2001: A Space Odyssey transcends the medium of cinema to become not just one of the best movies ever made but also one of the most important works of art created by humans. Likely no one will ever really figure it out but the movie stands on its own terms and it still stands tall, a monolithic giant of ambiguity and fascination.

Author Bio: Samuel Rafuse is a writer of certain charms. Sometimes he says funny things. They’re trying to make more of him but they lost the instructions.