Japanese anime are often about children, but they are certainly not primarily for a young audience. These films offer an insight into the subconscious of Japanese society. A country that during the Second World War believed in the irrefutable military power of the state and the myth of the “divine wind” –the self-sacrifice of the kamikaze pilots. However, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan had to face the truth that there was a bigger power than its god-like emperor–the United States.

The most remarkable pieces of the previous century, Akira, Ghost in the Shell, The Grave of the Fireflies, and Nausicaa from the Valley of the Winds were in one way or another, engaged with the nightmare of the Second World War, the shadow of which was overcast on Japan’s national identity, as well as the responsibility humanity played in the invention of weapons of mass destruction. At the same time, the self-reflective topic of a hyper-technocratic society also emerged, setting the question whether the quick absorption of Western technology will lead to the birth of a new demon to finally demolish what once was the Land of the Rising Sun.

While some of the anime produced after the millennia appear to be a resumption of this topic (Metropolis, The Wind Rises, Ghost in the Shell: Innocence), the bigger picture offers more hope than the movies of the ‘80s and the ‘90s. The children of these anime, the representatives of the Generation Y, appear to be fighting a different battle from that of their ancestors.

Their greatest challenge is to find a way to cope with the problems of everyday lives: the loss of a father (Wolf Children, A Letter to Momo), the uncertainties of teenage life and lack goals (The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, 5 Centimeters Per Second), or the difficulties of finding one’s own identity (Spirited Away, The Cat Returns). While these problems might seem banal compared to the annihilating monsters of earlier movies, this is the generation who carries the difficult task of finally shaking off the shadows of the war and finding a way to live on. This list features the twenty best films of the Generation Y that you should definitely see. But note that while most of them can be found on Netflix, they’re mostly only available in European markets. If you are not from Europe, you’ll need a Netflix VPN with servers in Europe such as ExpressVPN.

20. A Letter to Momo (Hiroyuki Okiyura, 2011)

The experience of loss, life in the metropolis compared to that in the countryside, and the little demons of Japanese folklore are compulsory ingredients of a good Japanese animation for all ages. Sure enough, A Letter to Momo features all these, with a good amount of humor and emotional moments in addition.

The scary-looking, but friendly ghosts definitely provide a few good laughs while they help Momo cope with the loss of her father. For those who are able to appreciate slower paced movies, it is touching to see how Momo gradually realizes that she isn’t the only one who has suffered and that her relationship with her mum needs to be reconciled.

Although this anime does not compete with the magical perfection of Spirited Away, in the shadow of some purely funny and entertaining American animation, it is delightful to find gems like this, where wit is combined with a heartwarming, humane story. Nothing proves this better than the selection of awards A Letter to Momo won between 2012 and 2014: Tokyo Anime Award, Awards of the Japanese Academy, Asia Pacific Screen Awards and Annie Awards.

19. From Up on Poppy Hill (Goro Miyazaki, 2011)

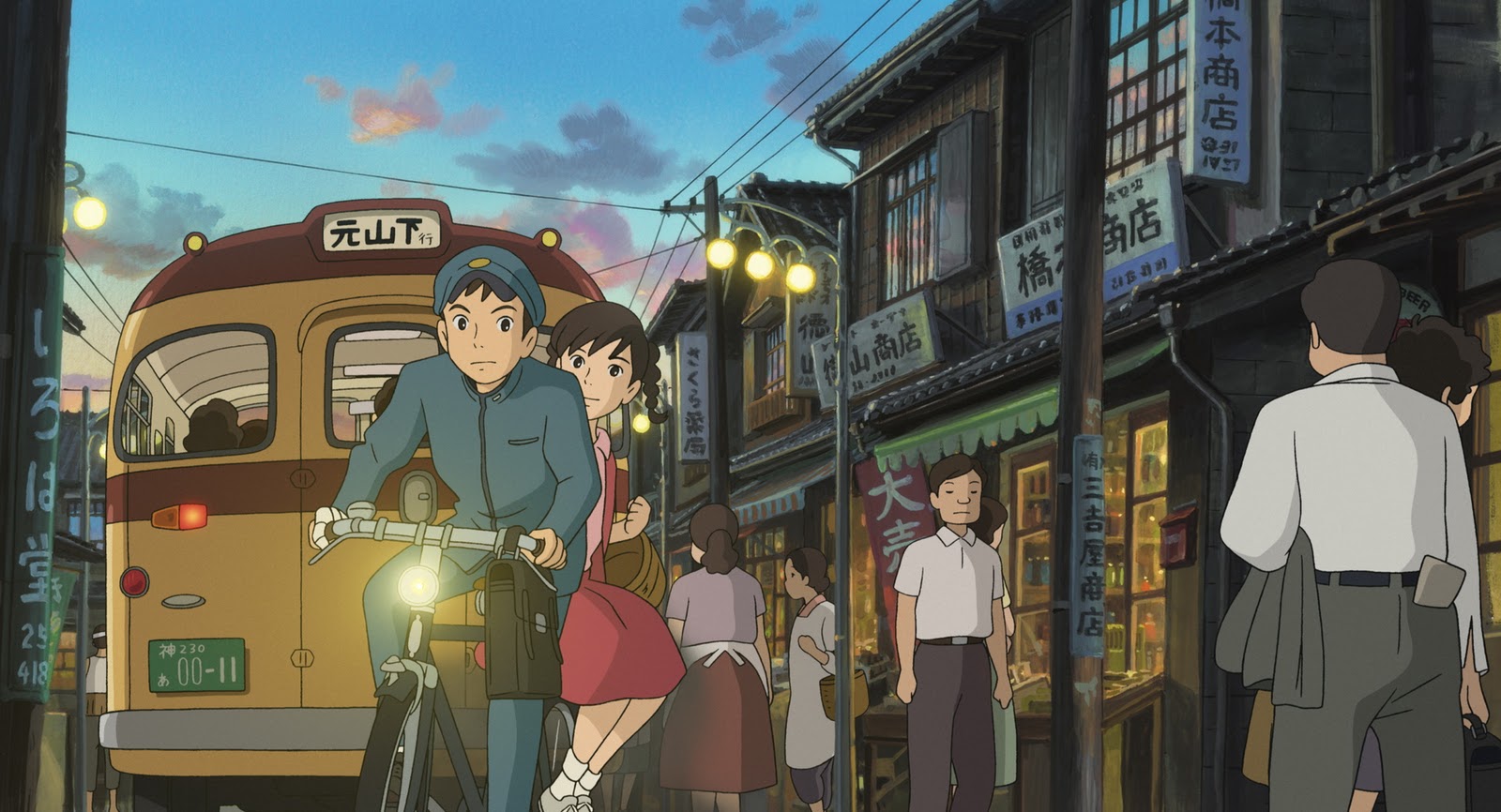

Hayao Miyazaki’s son, Goro Miyazaki failed to prove his talent with Tales from Earthsea, his directorial debut in 2006, which, to put it mildly, was not a great success. His second film, however, is the work of an already matured director, a beautifully entertaining Ghibli production that is in line with the studio’s best movies.

From Up on Poppy Hill is set in the past and is the story of a group of school kids who try to save their clubhouse from closing down. As an adaptation of an ‘80s shoujo manga, the film deploys the best elements of the genre: the happy moments of youth, budding love, and a generally invigorating atmosphere.

In contrast to the magical world of his father, Goro Miyazaki positions himself closer to reality. His heroine, Umi, is much closer to Isao Takahata’s characters in the Graves of the Fireflies than to any of the half-magical Miyazaki heroines, although her grace and strength can be compared to that of Naisicaa or Chihiro. Generally speaking, From Up on Poppy Hill is the best historical shoujo anime as of today, with great character design and Satoshi Takabe’s excellent score.

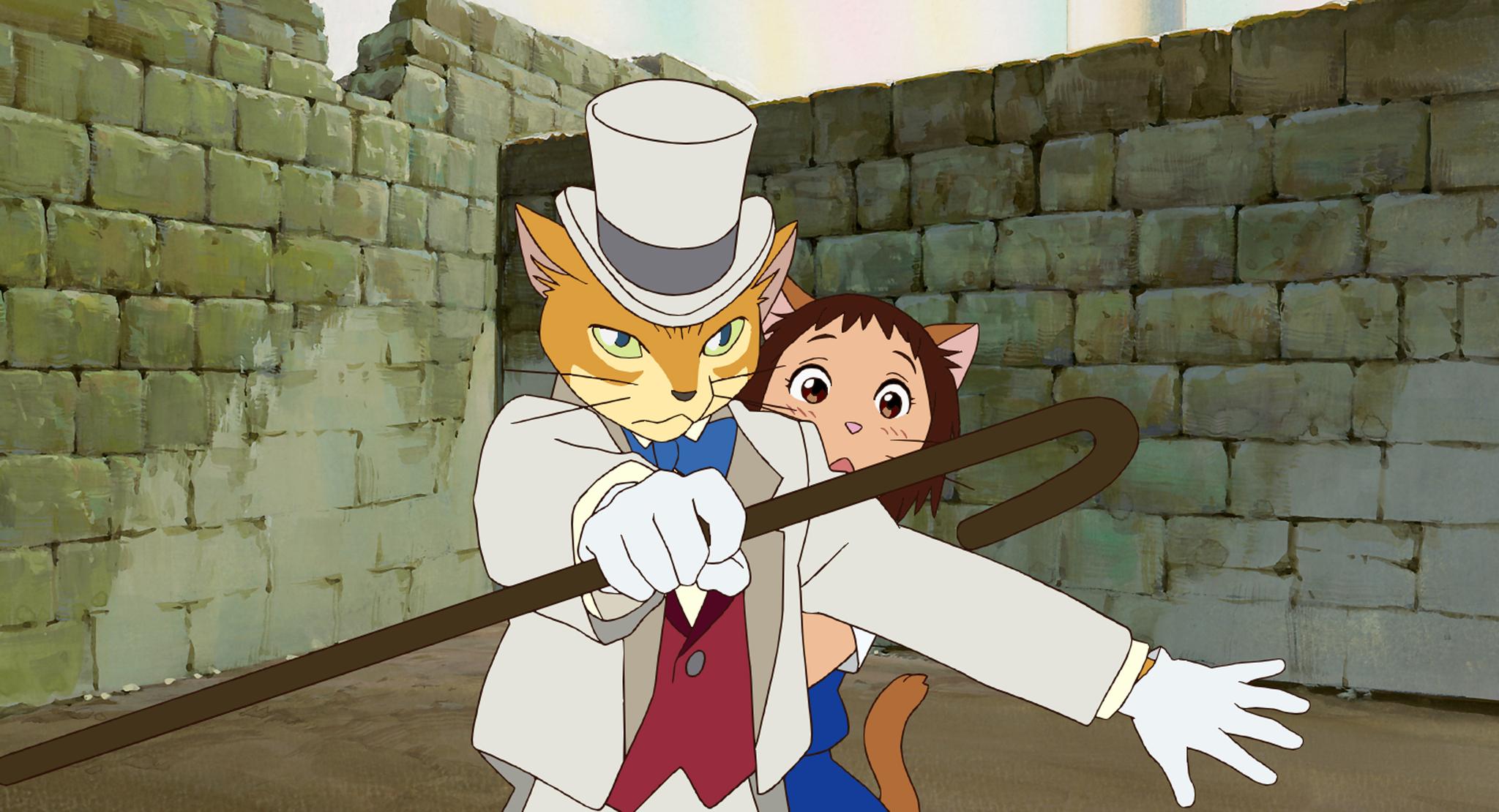

18. The Cat Returns (Hiroyuki Morita, 2002)

The Cat Returns started as a short animation commissioned by a theme park. Although the commission was cancelled, Hayao Miyazaki didn’t give up on the project, and extended it to a sort of test film for new Ghibli directors to be overseen by Hiroyuki Morita. Over time, the film expanded and based on Morita’s storyboard, The Cat Returns emerged as a playful, experimental anime. As an homage to the old Ghibli directors, the movie features Baron Humbert von Gikkingen and Muta, the fat cat, from Yoshifumi Kondo’s Whisper of the Heart (1995).

The inhabitants of the Cat Kingdom represent the rest of the cast, and Haru, the (partially) human girl, receives the unwanted reward of having to marry the cat prince Luna after she saved his life. Haru’s journey to the Cat Kingdom is similar in some ways to that of Chihiro from Spirited Away; in order to find their real selves, they first have to lose themselves. Haru turns into a cat, while Chihiro loses her name and becomes Sen, and they can only retrieve their original forms once they are in possession of the knowledge of how to keep their integrity in the everyday life.

Because of this similarity and the two cameo characters, The Cat Returns is often treated as a weak alloy of Spirited Away and Whisper of the Heart; however, it is a beautiful and playful instructive tale on the complicated Japanese culture of exchanging favors.

17. Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki, 2004)

Although not the best Miyazaki film of the twenty-first century, Howl’s Moving Castle deserves a place on this list. The moving castle itself is one of the most graceful Miyazaki creatures. As a medley of organic and steampunk shapes, it embodies the ideal unison of nature and the technical world. Meandering in the Wastes between two hostile countries, Howl’s castle is the place where the cursed Sophie seeks refuge as an old lady.

Some elements of this anime recall the story of The Wizard of Oz, especially the character of the Witch of the Waste, who puts the curse on Sophie out of jealousy, and Turnip Head, the scarecrow she encounters on her way to Howl’s castle. Although this universe is home to several Western fairytale characters, it also features the demon of the military power, which is most evident in the scene where giant bombers leave a city behind in flames.

As he turns the wicked witch into a harmless old lady, Miyazaki’s statement is that of transnational pacifism. He does not seek a party to blame or a stronger enemy to beat the opponent, but reconciles East and West in a transnational fairytale.

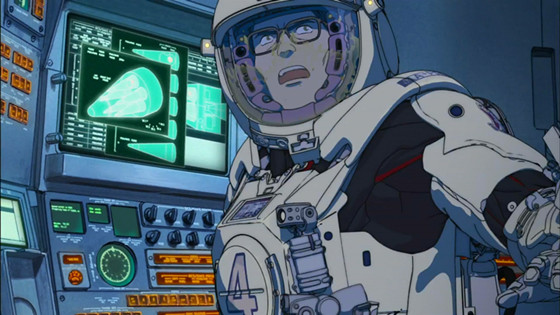

16. Short Peace (Hiroaki Ando, Hajime Katoki, Shuhei Morita, Katsuhiro Otomo, 2013)

Short Peace is a collection of four short films. Katsuhiro Otomo, who managed the project, collaborated with three remarkable anime artists. Two of them, Hiroaki Ando and Shoei Morita, worked with the director before, on Steamboy and Freedom Project, respectively, but none of them had directed a feature film as of yet.

Morita’s short, Possessions, features a samurai who has to mend various symbolic items on order to escape from a shrine. Otomo’s Combustible evokes the style of traditional Japanese paintings, but the starting shots also resemble a computer game. Hiroaki Ando’s Gambo also features painting-like visuals, enhancing the importance of traditional animation in opposition to the more prominent CGI. The beauty of these three shorts lies within their reference to Japanese religion and classic art, but Combustible is the one that manages to be the most innovative in its visual style.

In contrast, to the three stories about the past, Katoki’s Farewell to the Arms is a dystopian sci-fi. The longest, and also the best, in its animation technique, the most notable about this episode when compared to other sci-fi anime is the complete lack of the metropolis. In place of the city there is only decay as the war of men and machines reaches a new level. Short Peace is a great demonstration of what the most innovative animators of the time are capable of, and hopefully Ando, Katoki, and Morita will soon get a chance for a full-length directorial debut.

15. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (Mamoru Hosoda, 2006)

A lighthearted coming-of-age movie about a girl, Makoto, and her two male friends, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is not a sci-fi anime, as the title might suggest. In this anime, Mamoru Hosoda does what is his strength: depicting the simple beauty of life in modern Japan.

Although some fans tend to presume the problem of time travel makes the film more complicated than it seems at first glance, there is no need to speculate over the nature and theory of time travel to enjoy this movie. Moreover, the fact that some characters can transport themselves back in time is secondary to the plot, since the main focus is on how Makoto will be able to preserve her friendship with the two boys and find a purpose to her life other than just having fun.