7. Wolf Children (Mamoru Hosoda, 2012)

Mamoru Hosoda’s anime kicks off as a simple romantic story featuring a young university student, Hana, who falls in love with a mysterious boy attending the same lecture with her. It turns out that her lover is a werewolf, but not surprisingly, it is not a problem for Hana. Wolf Children is very much like a shoujo anime (a romantic story intended for a young female audience).

However, it is worth giving this film a few more minutes. When Hana’s lover dies leaving her with two babies/cubs, Hana’s struggle to raise her kids becomes the central conflict. One can rarely see such a comfortably lonely female character on screen. With two kids who cannot control their animal instincts, Hana chooses to dedicate her life to their upbringing, and she does this with grace and pleasure. There is something eternally sad in how Hosoda depicts this lonely woman who sacrifices her life for the sake of her family, but it is also heartwarming how the kids and their mother find their own ways to achieve a content life.

6. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki, 2013)

For those who love Miyazaki films only because of his usual fantasy elements, The Wind Rises, an historical anime, might not be the best choice for a big night in. However, this movie has its own great qualities. Miyazaki is at his best when it comes to machines, especially flying machines.

The Wind Rises tells the story of Jiro Hirokoshi, the engineer who designed Japanese fighters, but as usual with Miyazaki, there is more than this one layer in the story. Hirokoshi himself is a dreamer with a fierce obsession about flying machines and engineering – similarly to the director himself. However, the real Miyazaki alter ego in the film is Caproni. The Italian engineer takes Hirokoshi on fantasy trips aboard his plane, where they discuss the eternal freedom of flying and the endless possibilities of plane engineering.

While Caproni dreams about these machines as a means of transport, Hirokoshi constructs weapons; therefore, the ethics of war come into focus as well. Does the responsibility lie with the engineer who creates a killing machine, or with those who turned his beautiful dreams into a demon? Despite the somber philosophical question, The Wind Rises remains a beautiful tale about passion, love, a ghost of an ancient Japan, and flying machines.

5. Paprika (Satoshi Kon, 2006)

The subconscious and the dangerous powers of dreams are Satoshi Kon’s main topic. He explores this in Perfect Blue (1997) with its storyline of a pop-star-turned-actress who is being stalked by a mentally unbalance fan. Paprika sinks one level deeper into subconscious, to the realm of physical dreams, where a machine, which registers and opens up patients’ dreams, is stolen.

At this point, everyone who is dreaming is in danger, as the criminal targets the collective subconscious and invites people on a Danse Macabre as the Dream Land slowly invades the real world. Doctor Atsuko Chiba, the therapist, enters into this realm using her alter ego Paprika, a red-haired angel, to prevent the tragedy.

However, what does Satoshi Kon really mean when he talks about dreams? The character of the asexual Chiba, who turns into the beautiful Paprika in the dream world, is a clear reference to Freud and the gender conflict. Furthermore, there are several hidden references to such films as Tarzan, Roman Holiday, Perfect Blue, as well the movies of Kurosawa, suggesting the main source of illusions and distress is the film industry itself, as a creator of beautiful dreams.

4. Tekkonkinkreet (Michael Arias, 2006)

Director Michael Arias is an American-born filmmaker primarily working in Japan. Knowing the background of the author, one is perhaps compelled to be on the lookout for every little sign that differentiates Tekkonkinkreet from the rest of the films on this list. The most apparent novelty is its art style.

It is a truism that anime characters usually don’t look Japanese, but ironically enough, this anime director of American origin shakes off this tradition. Arias’ characters are far away from the usual ”big-eyed” appearance, which was borrowed from Disney, and are much closer to appearing realistically Japanese in their features. The rest of the rich visuals, the realistic representation of cityscapes, is something not alien to other Japanese animations, but where this movie really lives and breathes are the fantasy scenes.

Against the backdrop of a Yakuza battle over the reign of the imaginary metropolis, Black and White, the two street kids, fight for their lives on a physical and metaphorical level at the same time. The latter is what gives the most extraordinary moments of the film. With fantasy and reality interlocked in a visual orgy, White’s silent visions embody hope and love, while Black struggles against the dark powers of the antagonistic external world.

3. Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (Mamoru Oshii, 2004)

Ghost in the Shell: Innocence is the sequel of Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 anime science fiction, which revolutionized the genre by combining cel animation with CGI. In Ghost in the Shell (1995), the last remnants of the biological entity the brain tissue provided the spirit enclosed in a mechanic body, while in “Innocence,” (2004) this spirit can be duplicated and reproduced infinitely.

The borderline between human beings and machines gets close to redundant in this anime, in which Batou, a cyborg detective, tries to solve the mystery of murderous and suicidal sex robots. According to Oshii, the self is not necessarily a subject of biological cells, and robots can be more human in their suicide than human beings who create machines to deceptively satisfy the primary biological drive, which is the desire to reproduce.

In terms of visuals, the film lives up to its predecessor. It is an eye-catching combination of CGI and the traditional form of animation, resulting in a sharp, clean style and fluid motion of beautifully drawn images. As a companion of the cyborg detective, it naturally features the signature sad face of the director’s basset hound.

2. Metropolis (Rintaro, 2001)

In 1949, Osamu Tezuka created a work similarly significant to Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis, giving birth to Michi, the humanoid robot in his manga. This android embodies humanity’s frustration in relation to the destructive technological power of modern warfare, thus it is not surprising that it turned out to be the central character of most cyberpunk anime.

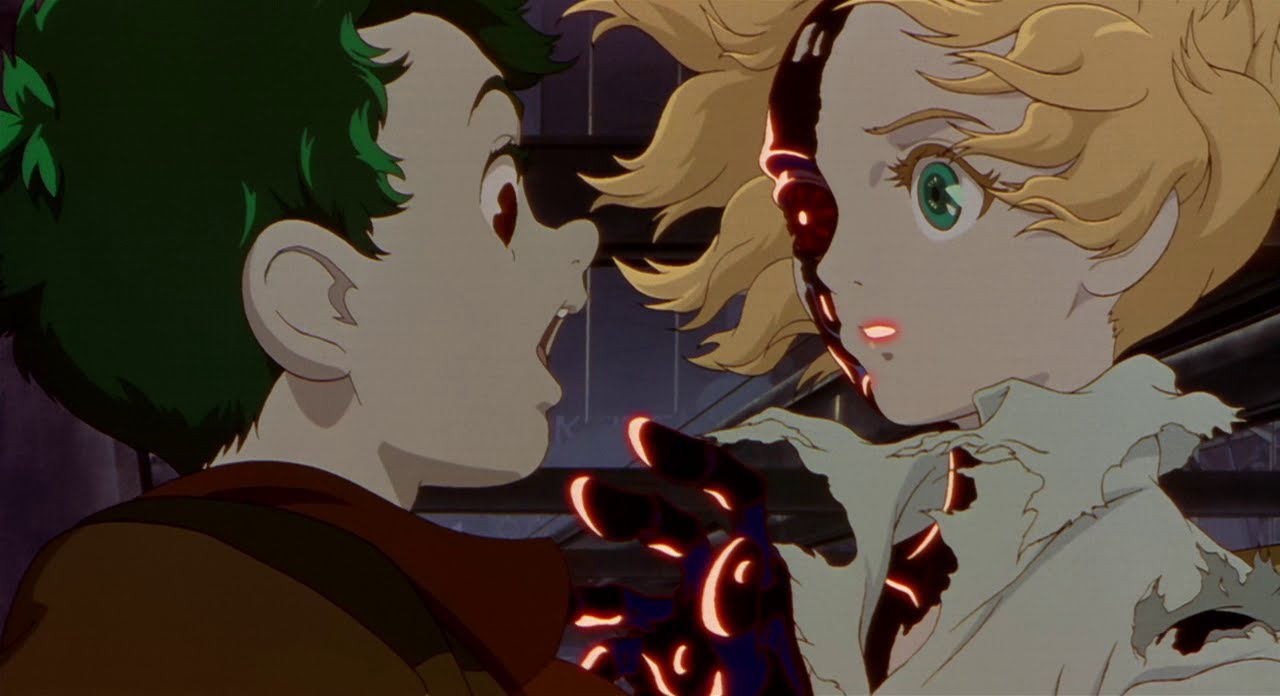

This 2001 adaptation of the manga substitutes the gender-changing Michi with Tima, the beautiful female android, who becomes the subject of Kenichi, the human boy’s affection. While in Fritz Lang’s film, and in the manga, the main focus is on the friction between the different social classes, in the anime, the opposition of human beings and machines replaces is the central point of the story.

Essentially Metropolis is a dystopian Romeo and Juliet story that escalates into a computer-controlled apocalypse. However, there is much more to it than the shadow of the overwhelming skyscrapers.

1. Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001)

The 2003 Oscar-winner Spirited Away is a coming-of-age story, a magical tale about gods and a heroine, a fable of how the modern world disrespects the past, and last, but not least, it is a visually stunning animated film. All this sounds exceptional, why exactly has this Miyazaki film become so well-known around the Western hemisphere?

Miyazaki’s stories usually unfold around the offset between nature and the ancient power of its gods and the disrespectful supremacy of the human world. Instead of the strong reference to Mother Nature, which is apparent in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Winds and Princess Mononoke, the spiritual world Chihiro enters is more evocative of an old society built on traditions, which is in danger of being overshadowed by the workaholic and technocratic modern world.

Chihiro’s quest to save her parents is also a little girl’s struggle to grow up in the modern age where the old family model is deconstructed. The magical power of Spirited Away hence lies within telling a universal story that is disturbingly relevant in the twenty-first century, with the addition of a big spoonful Miyazaki-magic.

Author Bio: Melinda Gemesi has been a freelance film critic since her second year as a Film Studies Student. She holds an MA in Film Studies and Online Journalism and is currently living in London. In her free time she is working on a literary project about which you can find out more on thestoryhunt.tumblr.com.