7. Hunger (Sult) / 1966 / Henning Carlsen

Based on Knut Hamsun’s pioneering modernist novel, Hunger is a masterful character study about a starving writer adrift in 19th century Oslo. Helmed by Per Oscarsson in a virtuoso performance that won him Best Actor at Cannes, the film lays bare the paradoxical extremes of the artistic temperament.

Pontus may be homeless, but his pride is without bounds. He writes on park benches, but cannot stand to share one. He asks the butcher for scraps to eat, claiming they are for his dog, yet assiduously declines the charity of others. He tries to pawn his glasses, but when he finds money he gives it all away. The only thing able to distract him from his work are the glances of the mysterious woman he calls Ylajali.

6. The Draughtsman’s Contract / 1982 / Peter Greenaway

Peter Greenaway’s second film is a beautiful work of craftsmanship: richly costumed and ornately scripted, it is also self-aware in the manner of something by Alain Robbe-Grillet.

Set in 17th century Britain and featuring a mock-Purcell score by Michael Nyman, it concerns a roguish sketch artist Mr. Neville (Anthony Higgins) who is hired by the wealthy matriarch Mrs. Herbert (Janet Suzman) to produce drawings of the estate grounds while her husband is away on business. A contract is drafted, which stipulates that Mr. Neville must also comply with Mrs. Herbert’s demands in the bedroom if he expects to receive his money.

In terms of plot, The Draughtsman’s Contract is like a maze. It’s virtually impossible to appreciate all its intricacy in one sitting.

5. The Color of Pomegranates (Sayat Nova) / 1969 / Sergei Parajanov

The filmography of Sergei Parajanov straddles three cultures. A Soviet citizen, he was born in Georgia to Armenian parents, and lived for many years in Ukraine. The Color of Pomegranates, his second ‘official’ film is a cinematic portrait of Sayat Nova, the important Armenian poet and musician from the 18th century.

However, as an intertitle explains at the beginning, the film is not meant to capture the biographical details of his life so much as his “inner world”, using the images and metaphors of the Ashough (“medieval Armenian poet troubadours”). What this amounts to is a procession of tableaux vivants divided into seven chapters, each representing a different stage of his life.

While the film’s relative lack of plot and foreign symbolism demand something from the audience, the effort is repaid in full by the astounding uniqueness and richness of its images.

One of the most daring formalistic experiments in the history of cinema, The Color of Pomegranates has deeply influenced several generations of experimental filmmakers, even if it has not received the universal acclaim of its predecessor Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

4. Edvard Munch / 1974 / Peter Watkins

From the first scenes of Edvard Munch, the 3-hour long biopic about the eponymous painter, one is struck by a number of odd details. The film is first presented under the guise of a documentary, ostensibly focused on the suffering of the urban poor of Kristiania, and narrated by Watkins’ own dry commentary. We are introduced to Edvard largely through cinéma vérité style interviews with his friends and family.

The obvious anachronism of the film’s presentation contrasts with other painstakingly realistic details, from the almost exclusive use of Norwegian non-actors, real locations, and dialogue sourced from Munch’s own diaries. This rigorous and unconventional method allows Watkins to depict Munch both in his exterior aspect as well as from a privileged psychological viewpoint, offering a portrait of unprecedented intimacy which at times borders on the hyperreal.

3. Crumb / 1994 / Terry Zwigoff

Crumb is an incredible documentary first of all because Robert Crumb makes for an incredible documentary subject. His physical appearance is exaggerated like one of his cartoons, his self-deprecating wit is omnipresent, and his personal life is almost too insane to believe.

Director Terry Zwigoff’s close friendship with Crumb allowed him to spend almost a decade recording him and interviewing his friends and family. The portrait that results is unsurprisingly one of rare candor. It also serves as an interesting case study about the link between artistic talent and mental illness.

2. La Belle Noiseuse (Sweet Troublemaker) / 1991 / Jacques Rivette

Jacques Rivette’s inspiration for this film was Honoré de Balzac’s short story Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu (the Unknown Masterpiece). Balzac’s story, highly regarded by Cezanne and Picasso, concerns a trio of artists, the distinguished painters Frenhofer (here played by Michel Piccoli), Porbus (Gilles Arbona) and the young Poussin (David Bursztein).

Frenhofer is a quasi-mythical figure, capable of performing miracles on the canvas, but is also wracked with hesitation and doubt. He tells the other two about an unfinished project, “La Belle Noiseuse” he abandoned 10 years ago, lacking a model. Porbus, unable to contain his enthusiasm, suggests Poussin’s beautiful lover Gillette (Emmanuelle Béart), and Poussin eventually agrees.

While not exactly an adaptation, Rivette’s film borrows the story’s principal characters and scenes, but adds considerable dimension to the plot with the addition of two female characters: Liz, the jealous wife and erstwhile model of Frenhofer (Jane Birkin), and Julienne (Marianne Denicourt) as Poussin’s sister and confidante.

Leveling out the male-female ratio of the cast, this addition adds interesting symmetries to the plot, turning the fable into a nuanced chamber drama. Lasting almost 4 hours, the film significantly alters Balzac’s ending, and Rivette included numerous subtle allusions to the text and to French artists that rewards repeated viewings.

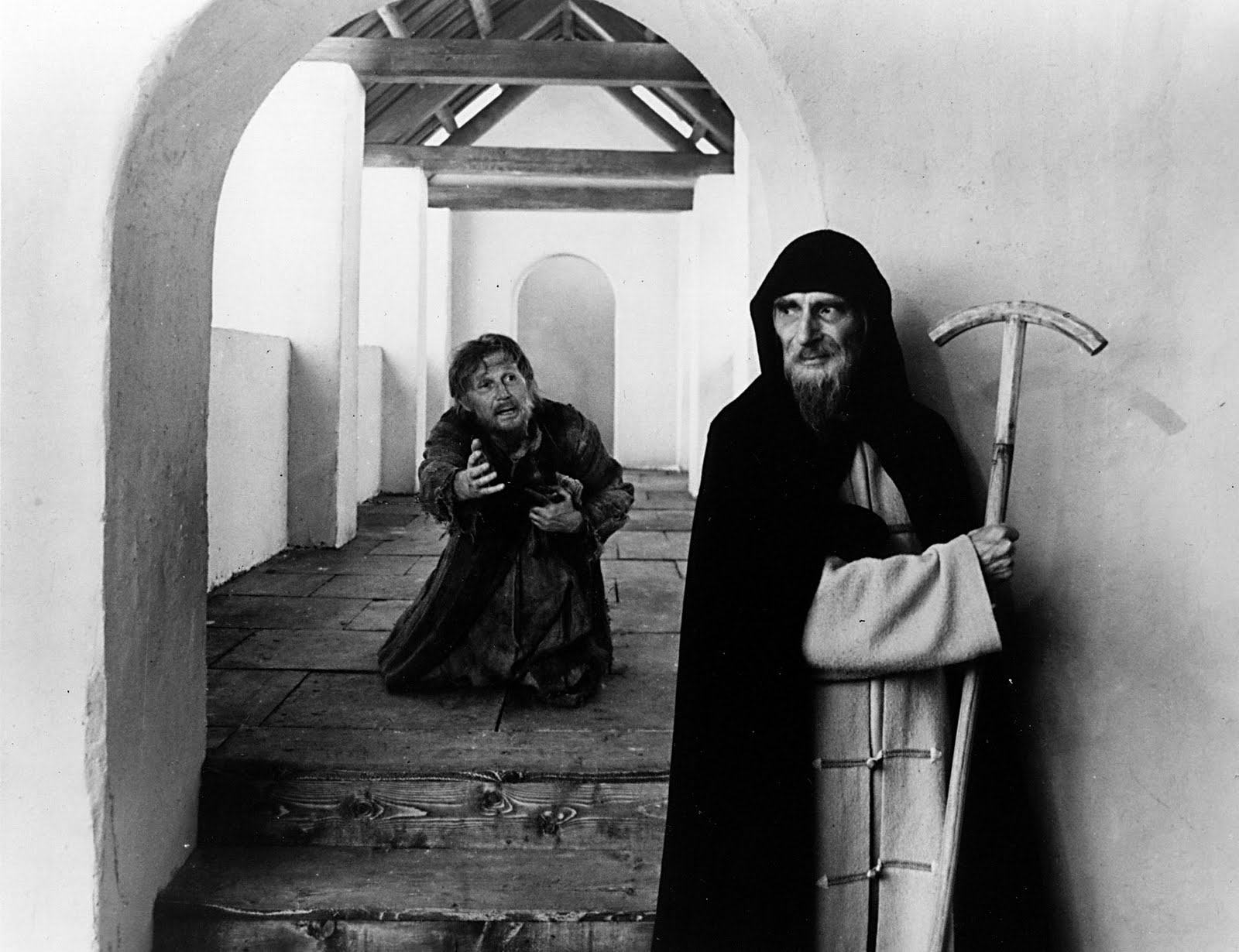

1. Andrei Rublev / 1966 / Andrei Tarkovsky

This sophomore film by Andrei Tarkovsky is a miracle – arguably never has a film wagered so much yet succeeded to such a degree. Its stylistic vision was drastically new, yet already fully formed, and Its subject matter could not have been more lofty, nor more politically inopportune coming from an atheistic USSR.

The titular character, played by Anatoly Solonitsyn in his debut role, is loosely based on the medieval religious painter and Russian Orthodox saint. The film consists of 15 novellas, broken into 7 chapters, a prologue and epilogue. Most chapters depict the painter at formative points in his life and career, but the film’s narrative flow and perspective are occasionally interrupted.

For the most part the film was shot in black and white and employs Tarkovsky’s signature extended takes, which help convey a contemplative mood. The film’s atmosphere is equally indebted to historical documents from the period as it is to the director’s own system of visual symbols, which lend a dreamlike feel. Other scenes contain impressive crane shots framing large crowds and vast expanses, giving the impression of an epic.

With Andrei Rublev, Tarkovsky sought to illustrate the complex relationship between an artist and his time. Highlighting the humanistic character of Rublev’s work, he imagines the artist as a Christlike figure, a receptacle for the hope and pain of others, yet whose own faith is constantly being tested.

Author Bio: Leo Greene is a cinema major graduate from NYU, some of his favorite filmmakers are Tarkovsky, Robbe-Grillet, Tati, Bunuel, Bresson, Oshima and Zanussi.