From Merriam-Webster.com: Father: 1a : a man who has begotten a child; 2a : one related to another in a way suggesting that of father to child; 3a: a person who was in someone’s family in past times.

All of those words are true enough but, somehow, they don’t quite say it all. The father is the progenitor, the protector, the provider, the disciplinarian, the authority, the ruler of the family. Right? Well, in a perfect world,.,maybe. These age old concepts leave that other important person, mom, out a bit but the thought of a strong head of the household being the father goes back to the beginning of human beings and their history.

In order for there to be a continuance of fathers a new crop must be planted and, to that end, sons (and daughters) come along. However, this is the point where many a problem can arise. The potential next father must grow and blossom and take his place in the world while the older father must eventually give way and decline in order for this to happen.

A wise father knows this and at least tries to maintain his legacy, his blueprint, by teaching the son to be like himself. This is where more problems occur. What if the son has ideas of his own or doesn’t like the way dad has lived his life or his ideas, which sons may find old fashioned or regressive (though quite often, after life experience of many years, the sons may find themselves returning)?

Adding to the complication is the fact that sons are quite often expected to be like their fathers. (Yes, the same goes for mother and daughter, but often not to so dramatic a degree).

All this being stated, its small wonder that when the movies tackle this relationship its quite often intense and dramatic, though, as will be shown, there are some humorous moments to be found as well.

One thing will not be on the following list: many may remember the highly synthetic father-son relationship portrayed in a series of films between impetuously juvenile Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney) and that bastion of middle class morality and upholder of American values, his dad, Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone). They had many a “man-to-man” talk the likes of which no real father and son would recognize.

To this end, this list wants to keep it real, one way or another, and so these are the notable films about fathers and their sons chosen:

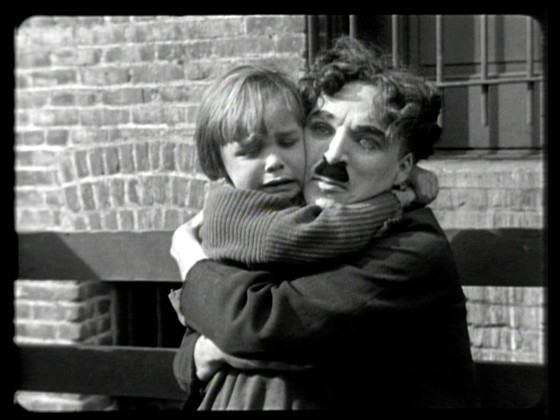

1. The Kid (1921)

The great silent comedy star-writer-director Charlie Chaplin eventually became father to ten children but, ironically, hardly knew his own. Chaplin was born into a milleau of performers and the man who may or may not have been his father floated out of both his and his half-brother Sydney’s life very early.

At the time that Chapling decided that he needed to step up from short subject comedies into features, he was both fatherless and childless. In light of that, it makes it rather touching that his first feature would concern a surrogate father-son relationship.

Chaplin plays his trademark character, The Tramp. The Tramp, a poetic n’er-do-well, who often finds and befriends pitiful, sometimes feisty, waifs on his journeys. Most of the time the waifs are comely young women in beleaguered circumstances but in this film such a young lady gives him a different challenge in the form of a child “born of shame” that she is forced to abandon.

She leaves the child where she hopes a millionaire will find and adopt him but The Tramp finds him first. The little boy matures into Jackie Coogan, the first great child star of the movies. He and Chaplin have perfect chemistry as The Tramp, with no knowledge of children, ingeniously finds ways to raise the little tyke and teach him to be kind but slyly clever in a cruel world not sympathetic to the poor.

This is underlined when the authorities get wind of this unofficial relationship and decided to take the boy to a “proper home” or institution. As in all comedies of the period, the ending is rather happy but not without moments of heartbreak and there is teh unanswered question of the The Tramp’s continued role in the life of the child at the picture’s end.

The relationship between the child and the man is a created and evolved one, not a natural one, and the feeling inherent in this film is taken from so much of Chaplin’s early life in poverty and the identification with a child thrust out into the world alone, which he must have understood all too well. There are some fine gags in this film but the Chaplin-Coogan synergy is what truly makes it memorable.

2. Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1927)

Virtually always mentioned in the same breath as Chaplin in discussions of silent film comedy is Buster Keaton. Like Chaplin, Keaton was born into a performing world in which his familywas none too prosperous. However, Keaton knew his father, Joe, all too well.

The Keaton parents were long time performers when their child came into the world and were not above using the child to milk applause until the (very early) time came for the boy to join the act. It turned out that the boy had much more talent than the father, something that didn’t help dad’s drinking problem (which, sadly, would be revisited in the son’s life eventually).

There were often family relationship’s within Keaton’s films but none ever addressed father and son concerns so directly as his last great independent silent film, Steamboat Bill Jr. In this one Bill, Sr. (Ernest Torrance, one rough customer on screen), a longtime paddle boat owner on the Mississippi, is waiting for Bill, Jr. (Keaton) to return home from years at school and help him out with a furious battle in which he’s embroiled concerning a ruthless rival.

Well, Bill arrives and dad doesn’t know what to think as junior has obviously gone down a rather effete path during his school years (and is quite diminutive, especially next to hulking dad). Sensing dad’s deep disappointment (not that dad is making it a secret) the kid spends most of the rest of the film trying, mostly futilely, to win the old man’s approval (amongst many great comic set pieces).

As with most films of this time and type, the hero finds a way, saves the day, and shows dad that he is worth something. Yes, it’s played for laughs but any great comedy is invested with one or more truths that really aren’t so funny in real life and this one uses that core of truth in spades.

3. The Champ (1931)

The term “weepie” usually denotes lachrymose films which tell sad, emotionally overheated stories usually aimed at female viewers, But there are films of that sort aimed at some other segments of the viewing audience. Though there may not be as many male “weepies” (in theory, anyway) as female ones, film history is dotted with a number of them and this one may be the father-son weepie to end them all.

Directed by the great King Vidor and scripted to by Oscar winning screen writer Frances Marion (yes, a woman!) this film tells of the relationship between a boozy, down and out old boxer (Wallace Beery, an Oscar winner for this performance) and his son (Jackie Cooper, a big child star of the day), who the old guy has been raising alone since his wife, the boy’s mother, left to find a better life than the one she was living with the father.

The boy, in reality, is having to grow up fast and he’s more the parent than the father, a perpetual screw up. Things come to a head when mom (Irene Rich) reappears, having indeed found a better place for herself, and now she wants her abandoned son back, in order to provide a better place for him. The father won’t let go and vows to put away the booze and show he’s a reliable parent by pulling himself together for a big prize fight, though it may prove fatal to him.

This should be such nonsense but experts pull it off with fine work both behind and in front of the camera, with the major credit going to the incredible chemistry between Beery and Cooper (especially impressive due to the fact that the fatherless Cooper and happily childless Beery didn’t like one another at all).

Beyond that, who in real life hasn’t seen examples of a prematurely wise child caring for and loving a childlike mess of a parent whom mere logic dictates doesn’t deserve that care and love? This film puts a face on it.

4. I Was Born, But….(1932)

For someone who never had a wife and children of his own, Yasujiro Ozu, one of the great world great directors, certainly had an unusually keen understanding of family relationships and virtually all of his films concern those relationships in one way or another. One of his lighter and more delightful, but equally profound films is I Was Born, But…. (the title is from a Japanese idiom for which there is no precise translation).

This film concerns what happens when dad is shown to be human being, not a superman, and how two brothers must accept that fact and learn to still love and respect their father, though, in their eyes, he may not be a man among men.

As the film (which is silent, since the silent era lasted until the mid-1930s in Japan) opens as a family with two young sons is moving to a new neighborhood in the suburbs of Tokyo (and many may be surprised at how modern and western is all seems). The sons, like many newcomers, have troubles with a neighborhood gang and bullies at school and try to play hooky due to those forces but dad finds out and will have none of it.

When they get to know the bullies a bit better it turns out the one of them is the son of their dad’s boss and he arranges for them to see some home movies his father has taken showing that their father is something of an office clown. They are humiliated and decide to go on a hunger strike until dad stands up to the boss and becomes “more important.”

In the end they must face the fact that dad probably once thought that he was going to end up the kind of big man the two boys are sure they will become as adults. However, he, as they surely will, had to face facts and sometimes even proud and good men must grovel in order to provide for their families. This is one prime reason dad is the boss in his home and deserves respect, as the boys come to realize.

5. It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

This holiday perennial from director Frank Capra doesn’t need any introduction in general. However, many may miss that this film is actually about many things, not the least of which is the joys of family life that often come along with the responsibilities and burdens inherent in family relationships, especially inter-generational ones.

As many know, George Bailey (the great James Stewart) is a man on the brink. He has spent his life doing good for others only to see his own dreams go up in smoke. How and when did it all go wrong? Well, as a young man he was about to head off for the life of adventure he had long desired.

Then, on the night before he was to go he had a dinner table conversation with his solid, dignified but somewhat worn down by life dad (Samuel S. Hinds) who has spent his life running a threadbare savings and loan that has been the only thing standing in the way of the richest meanest man in town owning everybody (yes, Lionel Barrymore’s hissable Mr. Potter).

Dad is impressively noble and inspiring and George soon needs inspiration since Dad dies of a stroke that night and George must become his surrogate, caring for his widowed mom, saving the S&L from kindly but somewhat retarded Uncle Billy, and nurturing his younger brother to go off and have the life he had planned for himself. (That’s quite a feat since dad only appears in a handful of scenes!)

One of the things that pushes George to the edge is the feeling he has failed his own children. The pay off is that George is able to come to peace with what he has lost by looking with fresh eyes at what he has gained, not the least of which is the knowledge that he fulfilled his father’s legacy.

6. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Being a parent isn’t easy at any moment in time but when one must parent in a time and place when the world seems to be falling apart must feel like an unbearable load. Italy during and just after World War II was such a place, being a battleground for two ferociously opposing forces who seemingly had little to no concern for the innocent people caught in the middle.

Out of this grew Italy’s famed Neo-Realist film movement which took non-actors and asked them to play out their real life situations on the locations which the situations did or could have taken place and shot them with the most basic of equipment to achieve a documentary like quality the captured the true feeling of that moment.

One of the key works of the movement is this film, which stills has the power to move viewers to an impressive degree. In this all too believably tragic story Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani), a family man who is desperately looking for work in post war Rome finally finds a job putting up movie posters around town, although the job requires the use of a bicycle to get around town and Antonio has none. His wife pawns her heirloom bed sheets, the family’s last possession of any real worth, for the bicycle.

However, very shortly after Antonio and his small son Bruno (Enzo Staiola) start work someone steals the prize bicycle. The rest of the day sees father and son frantically searching for the item until Antonio is forced to try to commit a shameful act in front of Bruno.

The film is so powerful and so heartbreaking because of somuch injustice which is seen in the context of the child’s view and that of the parent who loves him. The family shouldn’t have to be living in such circumstances. The prized job is really just a pitiful stop-gap that Antonio surely wouldn’t have considered in better times.

The thief was probably just as desperate as Antonio. Antonio shouldn’t, and surely wouldn’t in other circumstances, have tried to do what he does at the climax. And Bruno sees it all. And there is no happy ending or particular cause for hope except that humans have a facility to survive and Antonio at least seems to be teaching Bruno that one has to keep fighting to even do that. And it all rings true.

7. Shane (1953)

Surely almost everyone has had a fantasy in their youth that the parents raising them aren’t really their parents but some glamorous or impressive or dynamic person is really their parent and, for some good reason, just left them to be raised by others. Though that idea is never expressed as such it is truly at the heart of the classic western Shane.

Shane tells a story well-worn even in 1953, when the film was released. A group of settlers are building homes and fencing off the range in 19th century Wyoming, much to the ire of the cattlemen who came long before and wish for the range to remain free and under their control. One of the families is the Starretts, father Joe (Van Heflin), mother Marian (Jean Arthur) and, significantly, son Joey (Brandon de Wilde).

One day when a group of cattlemen come to menace the family or worse they are rescued by Shane (Alan Ladd) a striking man in light buckskins and a gun belt who has stopped to water his horse. Though he never reveals anything about his past and the particulars of it are never known, its plain that he’s lived his life as a gunslinger and it hasn’t been pretty.

The man decides to stay on with the Starretts as their hired hand and see a glimpse of the life he never had and, as it turns out, can never have. However, violence will come calling and Shane’s daydream can’t be realized anymore than he can be the adoring boy’s father. The one thing among others that makes this film work so well is the presence of the boy.

Everything is seen through his eyes and becomes bigger than life because of it. However, the child must grow into a man and the action of the film lasts long enough for Joey, who shares his father’s name and legacy, to see that his worship of Shane, who looks like a super hero to him, was just a passing childhood fancy (and he also realizes that mom has loved Shane also, though nothing came of it).

The ending is so haunting because Shane is passing into history, as he must, and that Joey has lost part of his childhood innocence, has he must.

8. To Kill A Mockingbird (1963)

When many hear the title “To Kill A Mockingbird”, whether referring to the original novel or the film version, the first thought concerning it is of it being a civil rights story. This is true enough but many returning to the story may be surprised to find that most of the book and much of the footage really concerns the family life of the main character, lawyer Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck).

Since the story is told through the eyes of Finch’s younger child and daughter, Scout (Mary Badham), many overlook that it is equally about the man’s relationship with his son, Gem (Phillip Alford).

Atticus, in the novel and film, had married the children’s deceased mother and had become a parent late in life. As the story opens, Gem is furious that Atticus won’t join the church football team with the other boy’s younger fathers. Motherly neighbor Miss Maudie (Rosemary Murphy) tells him to be thankful for such an accomplished father who is sensible enough to act his age.

Gem will have to learn this in stages such as watching his father shoot a rabid dog and discovering that dad had been a crack shot and modestly never had mentioned it. More importantly, though Atticus could not prevent the tragic injustice at the core of the story from taking place, he provides a great example for his kids by standing up for what is right, even if doing so ends in a thankless, sad place.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a tender memory piece told through a nostalgic lens but even if the Atticus wasn’t really all that, it plays well on film to have him portrayed in such a manner.