Despite the name, “horror movies” are not always necessarily the ones that most horrify their viewers. After all, the appeal of horror films usually isn’t their promise to traumatize or emotional scar, but to entertain via the skillful manipulation of fear and suspense. And while some horror films are certainly more extreme than others (Martyrs, The Last House on the Left, Cannibal Holocaust, etc.), overall, people don’t go to see them to have a bad time.

In fact, when a horror movie does go out of its way to truly disturb (think the ending of The Mist, for example), it’s almost seen as a shocking surprise. Horror movies often have high body counts and frequently contain gory and gruesome imagery, but their monsters – otherworldly or otherwise – are usually relatively easy to compartmentalize.

The makers of the films on this list, however, had no such interest in protecting the psyches of their viewers. Unlike traditional horror films, these entries lack the obvious trappings of that genre, and by definition, contain no elements of the supernatural. They are almost all dramas, with a couple of VERY dark comedies rounding out the list. Either highly plausible or in some cases inspired by or based on real events, these are the kinds of films that refuse to leave us, often rendering their viewers shaken for days. They truly horrify, in every sense of the word.

As a note of clarification, this list will exclude documentaries – plenty of which would certainly qualify as horrifying (Earthlings, The Act of Killing, Dear Zachary, etc.) – as well as films whose primary intent was clearly to disgust the viewer and do little else (A Serbian Film, Pink Flamingos, the three (sigh) Human Centipede movies).

All of the following films have clear messages, and the stark and disturbing reactions they commonly elicit are, more or less, justified by the importance of the stories they tell. Whether this makes them qualitatively “good” is, of course, purely subjective, but there is little point in arguing that at the very least they aren’t powerful.

25. Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978)

Based on Billy Hayes’s book depicting his hellish experience languishing in a Turkish prison after trying to smuggle hashish out of the country, Midnight Express features an Oscar-winning script by Oliver Stone that pulls no punches. Scenes of beatings, torture, and attempted rape comprise the running time.

And while both Hayes and Stone did both admit years later that the film is somewhat exaggerated – with the latter even apologizing to the Turks for it – there’s no doubt that whatever did in fact happen to the real-life Hayes (played in the film by Brad Davis) in Sağmalcılar Prison wasn’t pretty.

The film that put Turkish prisons on the map when it comes to gallows humor (remember the cockpit scene in Airplane!?), its biggest takeaway is perhaps this: If you’re going to break the law, do NOT do it in a foreign country whose penalties you’re not aware of – especially if that country doesn’t exactly have the best record when it comes to human rights.

24. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

There’s little to say about Stanley Kubrick’s masterful adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novella that hasn’t been written about already. Telling the story of a sociopathic gang leader named Alex (still Malcolm McDowell’s greatest performance, hands down) in a dystopian England, the film explores many controversial subjects, such as psychological conditioning, police brutality, juvenile delinquency, the balance of law and order with the rights of the individual, free will, and the nature of evil.

A violent, musical, unexpectedly funny at times tour-de-force, the film has both wowed and divided viewers since its release, original receiving the X-rating and ultimately being voluntarily withdrawn by its acclaimed director following a rash of alleged copycat crimes.

Now considered a classic, it’s a movie that, while undeniably horrifying on the surface, is so well made and entertaining that it’s hardly a chore to sit through. Its many satirical points (blunt as they sometimes are) and indispensable message about the importance of free will make it an inherently moral film that happens to be about an amoral person and the corrupted society in which he lives. Its relatively low ranking on this list may surprise some, though that just speaks to the potency of those to come…

23. Mysterious Skin (Gregg Araki, 2004)

Before he was a household name, Joseph Gordon-Levitt was in a number of well-regarded independent movies, including this one, which would likely shock many of his fans today. In this NC-17 rated drama, Gordon-Levitt plays a gay prostitute who was a victim of childhood sexual abuse. The film is a case study of the long-lasting effects of abuse on two eight-year-old boys at the hands of their baseball coach, showing how their lives went in wildly different directions as a result.

The scenes of abuse are shot as tastefully as possible, and were done in such a way as to not emotionally endanger the young child actors, but it’s still startling to see how far the filmmakers were able to go (largely through the use of careful framing and editing).

The film remains one of the most honest ever made on this tough subject, and its harrowing and unflinching portrayal of the impact of pedophilia on two innocent victims is memorable and deserving of praise. Though fictional, its central topic is tragically far too real and relatable for many.

22. Nineteen Eighty-Four (Michael Radford, 1984)

Appropriately made in the year of its title, this mostly faithful adaptation of George Orwell’s seminal novel about the ever-present dangers of totalitarianism retains the bleak ending and the pervasive dread of its source material. John Hurt is perfectly cast as Winston Smith, the protagonist and everyman who begins to quietly rebel against the highly oppressive system of the Party and its leader, Big Brother.

Living up to your iconic source material is never easy, especially when such material is one of the most important fictional books ever written, having influenced every dystopian work that’s been published since, and even having added many recognizable words to our general political vocabulary. Hurt himself starred as the villain (perhaps not so coincidentally) in 2005’s V for Vendetta, whose story owes more than a little to the world Orwell created.

It would be impossible for Radford’s film to surpass the novel in either importance or quality, but he does do an admirable job here, bringing the themes to life with disturbing simplicity. Never before has such innocuous a term as “Room 101” seemed so sinister.

21. Zero Day (Ben Coccio, 2003)

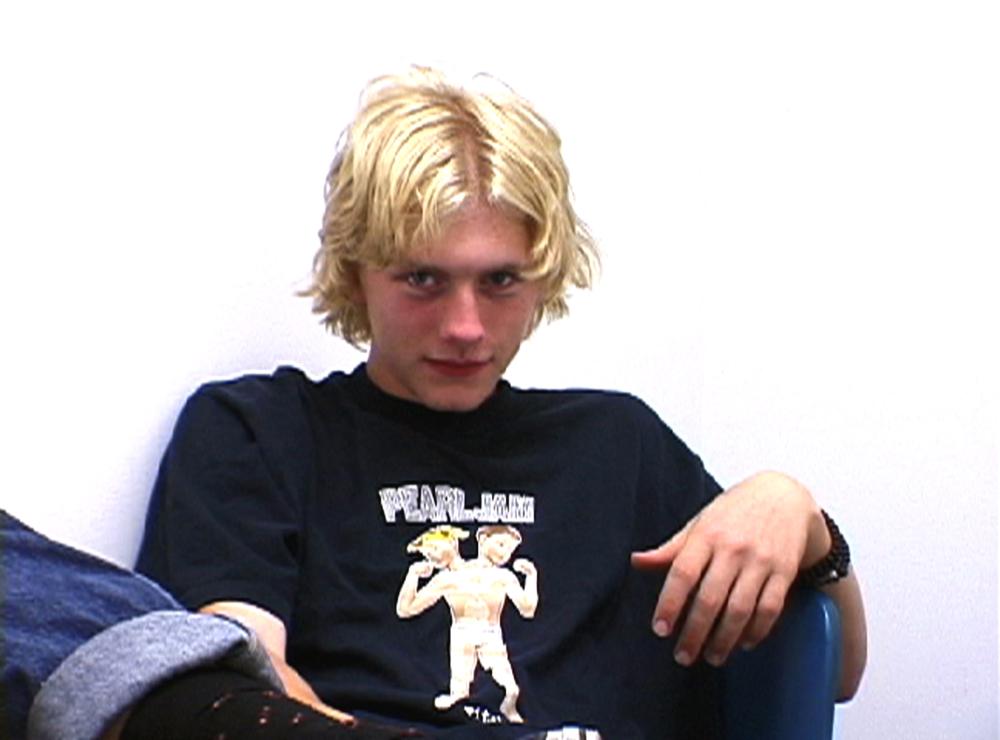

This little-seen low-budget film directed by Ben Coccio (co-writer of 2012’s The Place Beyond The Pines) is probably the best movie ever made (so far) about a school shooting – better even than the Palme d’Or winning Elephant released the same year, and Michael Moore’s controversial 2002 documentary. Clearly inspired by the Columbine High School massacre, Zero Day uses the found footage approach in documenting the activities of two teenage boys as they plan an attack on their high school.

Stars Andre Keuck and Cal Robertson bear more than a passing resemblance to real-life killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and many will find the 92-minute film almost too realistic and spot-on. After all, the shooters really did create video diaries prior to the events of April 20, 1999, though the infamous “basement tapes,” as they were dubbed, were never made public.

Think of this, then, as a fictionalized version of those tapes. The resulting film, devoid of theatrical camera angles or a tacked on score, comes off as downright eerie, and all the more relevant given the depressingly high incidence of such kinds of crimes in the U.S. that persist to this day.

The inevitable ending may strike some as anticlimactic in the way it’s shot, but this is likely due to Coccio’s attempt to refrain from showing the shooting in a way that could be construed as exciting or glorifying. It’s a rewarding viewing experience for those who seek it out, though an upbeat time at the movies it certainly is not.

20. The Stoning of Soraya M. (Cyrus Nowrasteh, 2008)

Sadly based on a true story, this adaptation of the 1990 novel La Femme Lapidée, by Freidoune Sahebjam, shines a light on a vile ancient practice that is still carried out in parts of the world today. The plot, told in flashback, concerns an Iranian woman named Soraya (Mozhan Marnò) whose abusive husband wants a divorce so he can marry a 14-year-old girl. When an opportunity presents itself to accuse Soraya of adultery (falsely), the wheels of injustice are tragically set in motion.

This isn’t the subtlest film in existence, and there are some unnecessarily contrived sequences included in an effort to amp up the tension. Despite its flaws, however, the film achieves its goal of outraging the viewer and then some. The title is a spoiler, of course, but that doesn’t make the climactic stoning scene any easier to handle. Shown in prolonged and graphic detail, it would be exploitative if it weren’t for the facts that a) this specific case really happened, and b) this barbaric practice still happens.

Sometimes the gruesome details should be left to the imagination, but other times, depicting them honestly and fully is the braver choice, as is arguably the case here. The first step in stopping a problem is raising awareness about it and showing it – no matter how horrible it may be.

Whether the casting of Jim Caviezel – who has some experience with films centered on torturous executions – as the French-Iranian journalist who hears the tale and ends up writing the book the movie is based on, is coincidental, is open to interpretation.

19. In the Company of Men (Neil LaBute, 1997)

The least violent film on this list is still an incredibly upsetting one. The premise is stomach-churning enough in its premeditated emotional cruelty: Two co-workers, the soft-spoken Howard (Matt Malloy) and the charming but sociopathic Chad (Aaron Eckhart) conspire to simultaneously woo and then dump a vulnerable young woman (Stacy Edwards), who also happens to be deaf. The film follows through on its promise to offend, though not without purpose, nor a few well constructed and unpredictable plot twists.

Far less simple-minded then it seems, this is an excellent illustration not only of misogyny at its most insidious, but the destruction that manipulative people can wreak when they’re properly motivated. It’s writer-director Neil LaBute’s most trenchant work till his near-equally unsettling The Shape of Things in 2003. An always-provocative filmmaker, his first film is also one of his strongest… and shocking.

18. An American Crime (Tommy O’Haver, 2007)

Based on a true story (could it possibly have been made if it weren’t?), this depressing drama depicts the lengthy torture and murder of a sixteen-year-old girl at the hands of the depraved woman tasked with taking care of her, the woman’s children, and other kids in the neighborhood.

A prosecutor dubbed the horrific Sylvia Likens case, which occurred in 1965, “the most terrible crime ever committed in the state of Indiana,” and it’s not hard to see why. The film is strongly acted, and more focused on documenting what gradually happened than in providing a satisfying explanation for it, though there likely isn’t one that could adequately elucidate why this tragedy occurred.

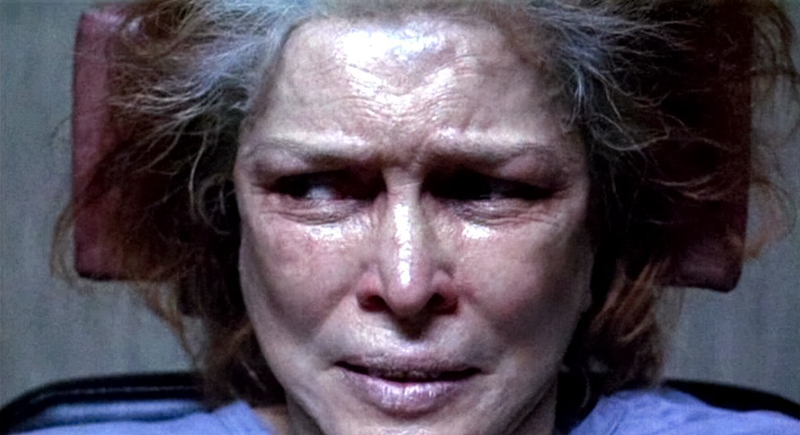

There was a second film made the very same year as this one called The Girl Next Door, based on Jack Ketchum’s novel. An American Crime is easily the superior of the two though, as it sticks much closer to the facts, is less interested in cataloguing the abuse in graphic detail, and stars two Oscar nominees: Catherine Keener and Ellen Page.

The particulars of the case, while ghastly, are fascinating on a psychological level (the number and young ages of most of the perpetrators are especially baffling). Still, many will be unwilling to sit through their reenactment here, no matter how accurately they are represented or measured the performances.