17. The Accused (Jonathan Kaplan, 1988)

Another film sadly inspired by a real event, The Accused took on the topic of rape in a more singular manner than had likely ever been done before by a major Hollywood film. Jodie Foster won her first Oscar (the film’s only nomination) for playing Sarah Tobias, the victim of a hideous gang rape perpetrated in the back room of a bar.

The film chronicles her pursuit of justice, as the assistant district attorney (Kelly McGillis) decides to specifically go after not just the rapists, but also the witnesses who allowed the crime to occur and, repugnantly enough, actively encouraged it.

A bit heavy-handed at times, the film is nonetheless gripping and worth watching. The attention paid to how Sarah was dressed, behaving, and her intoxication level immediately prior to the rape in an attempt to discredit her makes the film still relevant, as rape accusations all too often lead to unfair bullying and judging of victims before (or if ever) convictions are pronounced.

The decision to show the crime in full at the climax is a risky one, but a choice that ultimately proves to be the right one, its inclusion being necessary for the integrity of the film. While morally detestable, the scene lends the final product gravity that it would not have had otherwise, and is shot in a manner that could never be construed as erotic in any way. “Enjoyable” certainly isn’t the right word for this heavy film, but viewers who watch it in its entirety will have found it a worthwhile experience.

16. Johnny Got His Gun (Dalton Trumbo, 1971)

Adapted by Dalton Trumbo from his own book, this anti-war story is another film whose premise alone horrifies. Timothy Bottoms plays an American World War I soldier who has become deaf, blind, mute, and a quadruple-amputee following an artillery shell explosion. His flashbacks and fantasies (during which Donald Sutherland appears as Jesus) make up the bulk of the film, as do his attempts to communicate with the staff of the hospital in which he now resides.

The text at the end listing the number of war dead since 1914 and the ironic quote in Latin meaning “It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country” is a bit overly simplistic and makes the film’s message explicitly clear unnecessarily, but the sobering final scene it follows is downright haunting. In a film where we’re rooting for the protagonist to die out of mercy, can any ending be considered truly happy? In some ways, it’s like The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, only more political, and a lot less inspiring.

15. Deliverance (John Boorman, 1972)

This Best Picture nominee is one of those classics that deserves to be known for more than just a catchy banjo tune and one rather infamous scene. Adapted by James Dickey from his own novel, the film tells the story of four buddies, played by Burt Reynolds, Jon Voight, Ned Beatty, and Ronny Cox, whose canoe trip down a soon-to-be-destroyed Georgia river turns into a nightmare. “This is the weekend they didn’t play golf,” the tagline ominously informs us.

A decades-old film that’s still jolting to this day, Deliverance is a survival film that also features insightful social commentary and had some real-world influence, both positive (popularizing “Dueling Banjos – harmless) and negative (increasing tourism that led to several drowning in the river used for filming… not so much).

The rape scene that is the film’s centerpiece and the ugly depiction of hillbillies likely didn’t do much to endear the film to rural Southerners from the area, but the film’s impact as an entertaining and nail-biting adventure film cannot be denied. Its realism in particular is worth noting – in an effort to keep costs down, all the actors performed their own stunts, which would be unheard of today.

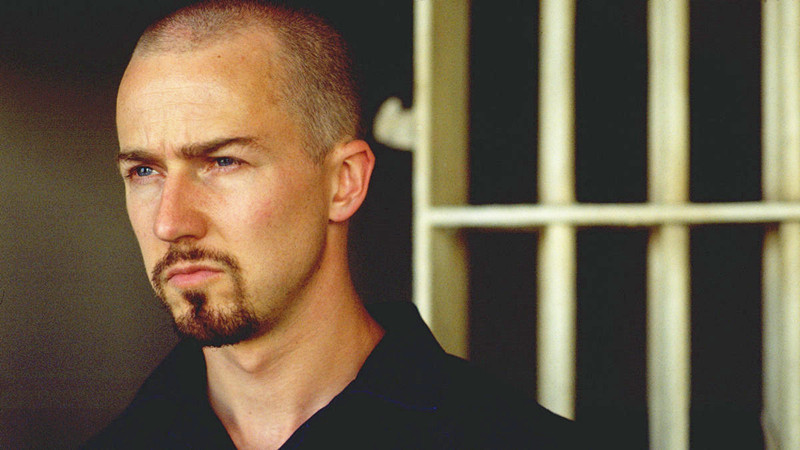

14. American History X (Tony Kaye, 1998)

One of the best movies ever made about racism, American History X succeeds by refusing to sugarcoat or simplify. Edward Norton mesmerizes (and earned the film’s sole Oscar nomination) in the lead role as Derek Vinyard, a reformed neo-Nazi desperate to keep his younger brother, Danny (Edward Furlong) from following in his dark footsteps.

Sporting a shaved head and a physique that required him to put on thirty pounds of muscle, Norton is simultaneously monstrous and surprisingly sympathetic, depending on the timeframe. The film shows the extent to which Derek once embraced the malicious skinhead mindset, and the journey his character takes in learning to renounce his violent and hateful ways.

The film is fittingly harsh and uncompromising, featuring a brutal rape scene, countless racial slurs, and one murderous act in particular that will stay with audiences far after the film has ended. That said, it’s also an incredibly powerful and poignant film whose message is both difficult and affecting.

Unlike numerous other films that tackle the issue of racism – specifically between blacks and whites – this one isn’t afraid to show the consequences of such worldviews in all their horror, as well as attempt to understand how such dangerous ways of thinking can develop in the first place, and alternatively, how they can have the potential to evolve and (hopefully) fade away.

13. Happiness (Todd Solondz, 1998)

Here we have another film that, despite its lack of violence, still has the power to appall with ease. Earning a spot on Premiere Magazine’s “25 Most Dangerous Movies Ever Made” list (along with a few others on this list), Happiness has multiple intertwining stories, mainly revolving around three adult sisters (Cynthia Stevenson, Jane Adams, and Lara Flynn Boyle).

While there are many disturbing parts, not least of which is Philip Seymour Hoffman’s depressed obscene phone caller, it’s Dylan Baker as an unrepentant pedophile who undoubtedly leaves the biggest impression. His frank admission of his deviant crimes and sexual appetites in a scene towards the end is stunningly honest and irredeemably heinous.

It is likely this aspect of the film that led to the MPAA slapping the film with the NC-17 rating (which it thereafter surrendered, going out unrated). While certainly not a movie for children or young teens, this ironically titled art film is both darkly funny and painful to watch. Its strong performances, deft balancing of tone, and willingness to engage with some pretty challenging material make it a praiseworthy and small triumph.

12. 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013)

Many were too scared to see this recent Best Picture winner, including, reportedly, some Academy members who voted for it out of a sense of obligation. This is a real shame, not just because it diminishes the credibility of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, but also because 12 Years a Slave was absolutely deserving of the honor it received. Its subject matter is a dark and shameful part of American history, yes, but this is also a damn good movie overall.

The harrowing true story of Solomon Northup (brilliantly played by an Oscar-nominated Chiwetel Ejiofor), a black man born free in New York, kidnapped in 1841, and forced into slavery for the (spoiler alert) twelve years of the title, leaves few horrors of the slave experience unexplored (save perhaps for the Middle Passage, which Spielberg authentically recreated in Amistad).

Steve McQueen’s expert direction immerses us in the cruel world of the antebellum South by filming in historic locations and not letting the audience off the hook when it comes to Solomon’s ordeal.

The protracted scene in which he nearly dies in a lynching seems to go on for an agonizingly long time, largely due to the unnatural length of the takes used. In effect, McQueen forces us to witness a mere representation of a relatively common atrocity at the time – something made all the more abominable by the beautiful scenery and seeming indifference of the plantation workers and fellow slaves around Solomon.

The fact that Solomon’s story is a true one, in contrast to the more well-known fictional novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (published just a year before the narrative brought to life here was), makes his story all the more important – one that demands to be seen, not matter how unpleasant its facts.

11. 127 Hours (Danny Boyle, 2010)

Another Oscar-nominated movie that many avoided seeing out of squeamishness, this is another example of a true story being brought to the big screen with the highest level of skillfulness and respect one could ask for.

Outdoorsman Aron Ralston (James Franco, in an Oscar-nominated performance) spent the duration referred to in the title trapped in a Utah canyon with his arm pinned against a boulder in 2003, and Boyle and co-writer Simon Beaufoy make you feel every one of those hours, keeping flashbacks to a minimum and refraining from cutting away to family or friends looking for Aron. We’re basically trapped there with him.

According to Ralston himself, “the movie is so factually accurate it is as close to a documentary as you can get and still be a drama.” As for the climactic and bloody amputation scene that we all know is coming, its depiction is indeed graphic, but the knowledge that what took roughly an hour in real life is shown in a matter of minutes (and apparently edited down from just one 20-minute take) is a mercy.

Besides, we are made to feel every excruciating second of the procedure, made especially unbearable through the use of unnerving sound effects and state of the art prosthetics. While the scene is indeed rough, skipping the movie because of it would do one a disservice, as the movie provides as a whole one of the more inspiring messages, albeit viscerally rendered, in recent memory.

Essentially, the story works not just as a cautionary survival tale, but as a metaphor that can be applied to anyone’s problems: We all get ourselves into messes at times, and occasionally the only good solution lies within… hopefully the answer just isn’t as physically painful as the one Aron had to go through.

10. Compliance (Craig Zobel, 2012)

With the capacity to perhaps make you angrier than any other film here, the plot of Compliance would be almost unbelievable if it hadn’t actually happened. The events of the film deviate little from an incident that occurred at a McDonald’s in Kentucky in 2004, in which a man claiming to be a police officer called and, slowly but surely, convinced the manager to strip search a female employee before things escalated even further.

Already being the basis for an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit that guest-starred Robin Williams in not-so-funny mode, the bizarre crime is reminiscent of the famous Milgram experiments on obedience – something the film refers to at its start.

Starring Ann Dowd as the manager, Dreama Walker as the victimized employee, and Pat Healy as the caller, the film created quite a stir when it premiered at Sundance. It’s likely to infuriate many with its depiction of unfathomably naïve behavior that leads to real harm, no matter how accurate and true to what really happened it is.

The details of the crime are respectfully handled, however – an effort having clearly been made to not make the icky reenactment feel exploitative – and the film ultimately works as a chilling illustration of the dangers of psychological manipulation, blind trust, and yes, perhaps simple stupidity as well.

9. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

One of the most controversial films ever made, Salò also proved to be its director’s last, as Pasolini was murdered shortly before its release (for unrelated reasons). Based on the book by the Marquis de Sade and updated to take place in Fascist Italy, it depicts the rape, torture, and murder of a group of teenagers by four sadistic libertines in a palace located in the Republic of Salò – a puppet state created in Italy by Nazi Germany. The film features constant nudity, cruelty, and doesn’t skimp on the depravity.

For the intrigued and curious, the main question is this: Is the film any good? The answer is debatable. For a film banned in several countries, it has plenty of high-profile admirers, including arthouse directors like Catherine Breillat, Michael Haneke, and Gaspar Noé.

Like the recent and similarly scandalous A Serbian Film, Salò is often defended as being about more than the atrocities it literally presents, with proponents arguing that the film is a metaphor for political corruption and the evils of fascism. How well the film supports this interpretation is up to the viewer, but make no mistake, it is guaranteed to leave you somewhat depressed and is at times genuinely revolting. Case in point: the segment entitled “Circle of Shit.” Let’s just say that’s not a euphemism…