8. We Need to Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, 2011)

The second best movie made about a school massacre (thankfully a fictional one), this film is downright creepy from beginning to end. Based on Lionel Shriver’s novel of the same name, the non-linear plot jumps back and forth between the present, in which Eva (Tilda Swinton) must cope with the aftermath of her son’s murderous rampage one day at school, and the past, which chronicles Kevin’s upbringing.

John C. Reilly gives a solid non-comedic performance as the oblivious father, while three actors play the boy at various stages of his life. As the oldest incarnation of the psychopathic Kevin, Ezra Miller is effectively repellent, imbuing the teen with both uncanny charm and diabolical malevolence.

A film as much about the essence of evil as the nature vs. nurture debate, it manages to maintain a foreboding atmosphere throughout, an achievement no doubt aided by a suitably dissonant and atonal score by Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead fame. Director Lynne Ramsay keeps us almost cruelly in suspense about the exact nature of Kevin’s crimes till the end, at which point his actions are revealed to have been even worse than we imagined.

It’s a movie that has all the hallmarks of a horror film without ever resorting to gore or needing a supernatural explanation, and blows every other “evil kid” movie out of the water with its shocking plausibility. You may think twice about having children after seeing this one.

7. United 93 (Paul Greengrass, 2006)

“Too soon?” This was the question posited in nearly every review of this outstanding docudrama, which tackles the fate of the only plane that didn’t reach its target in the unprecedented terrorist attacks that occurred just five years prior to its release. The answer doesn’t matter now, of course, which is a good thing, as generations will be left with this powerful testament to perhaps the most inspiring – though tragic – story of September 11th.

More than any other 9/11 movie, this is the one that best captures what it felt like that confusing September day for those of us old enough to remember it. Writer-director Paul Greengrass includes no melodramatic flashbacks, cutaways to family members of the passengers, or overt political context for what’s happening.

Instead, he limits the action to the experiences of the people on the plane, the men and women at the FAA (including National Operations Manager Ben Sliney, who plays himself), and a brief prologue in which we see the four terrorists preparing for the attack. Even they are treated fairly, depicted not as villainous cardboard cutouts, but as devout men who truly believed they were righteous and on a mission sanctioned by God.

The hijacking and subsequent events unfold in real time – one of the many decisions Greengrass makes that lends an unmistakable air of verisimilitude to the proceedings. Accuracy was of the utmost importance to him, so much so that he was able to gain the cooperation of the family members of all the plane’s victims, who provided the actors playing the dead with detailed background information to help make every performance believable.

The score by John Powell is effective without being too heavy-handed, and the track that plays during the climax (simply titled “The End”) was so stirring that Greengrass ended up recycling it for the climax of his 2013 film, Captain Phillips.

This great movie – one of the finest of the decade – is not exploitative in the least (a percentage of the opening weekend gross was even donated to the memorial in Shanksville, PA). It placed #1 on more critics’ top ten lists than any other film that year, and earned two Oscar nominations (for editing and directing). It has the tendency to leave audiences in stunned silence, which only speaks to its ability to capture the emotional loss it portrays.

6. The Grey Zone (Tim Blake Nelson, 2001)

Is this film, set in a Nazi extermination camp, better than Schindler’s List? By any measure of evaluation, the answer is no. That said, it certainly is more representative of the Holocaust than Spielberg’s black and white epic, which ultimately ends on a message of hope.

The Grey Zone, based on Dr. Miklós Nyiszli’s book, Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account, tells the story of the efforts made by the Jewish Sonderkommando – inmates forced to assist in the gassing and cremation process – to destroy the crematoria and gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Normally the inclusion of big name actors in such a somber film would be distracting, but here, people like David Arquette, Steve Buscemi, and Mira Sorvino slip into their difficult roles rather seamlessly (the same cannot really be said about Harvey Keitel, who plays an SS guard, but then again, he wasn’t especially convincing as Judas in Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ either).

The film leaves little to the imagination, confronting its grim subject matter head on (likely a reason for its dismal box office numbers). Nelson’s commitment to accuracy, including the building of a 90% scale reproduction of the camp using the original Auschwitz blueprints for the Bulgarian set – is commendable, resulting in an eerie realism.

The downer ending is inevitable, and the coda appropriately dark. Sometimes, comforting the audience is less important than being true to history, and in this vein, the film ends not with cautious optimism, but with unblinking incredulity at the evil perpetrated against those the Nazis deemed unworthy of life.

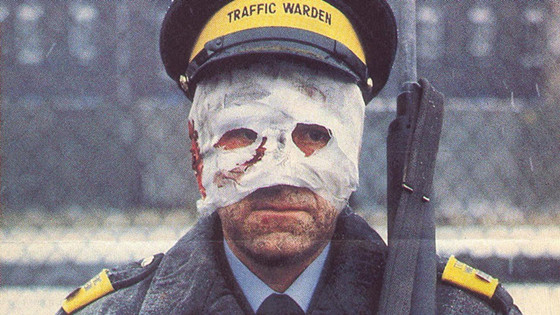

5. Threads (Mick Jackson, 1984)

The 1980’s saw the releases of several films centered on hypothetical nuclear disaster. While this British drama may not have gotten the same record-breaking number of viewers as the star-studded American production The Day After (aired just a year prior), it is both more realistic and bleaker. Heavily researched and made with the best of intentions, the film succeeds by being utterly terrifying.

Character development takes a backseat to the meticulously constructed political background, which in this case involves a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union triggered by a U.S.-backed coup in Iran (there are no fictional countries in this scenario). The film becomes almost documentary-like in depicting the events before, during, and after a nuclear strike on the English city of Sheffield, with two families providing a personal perspective on the calamitous situation.

After seeing the film, you’ll probably agree that genocide is only the second worst thing in the world, as the concept of nuclear annihilation threatens to leave no survivors at all. The film may lack the quiet devastation of the criminally underrated Testament (1983), which also conveys the terrible effects of nuclear war, but is far more visceral, thus having the greater potential to be nightmare inducing (as it should be).

4. Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985)

I’ve already written about why Come and See is arguably the greatest war movie ever made, so by definition, uninitiated viewers should not expect a frolic through the tulips. Through the perspective of an idealistic young teenager (Aleksei Kravchenko), we witness – as indicated by the title – the Nazis lay waste to the Byelorussian SSR (modern-day Belarus) and its ill-fated inhabitants.

The film was shot in chronological order, and by its end, we feel as drained and shell-shocked as its traumatized protagonist. Klimov pulls off the impressive feat of keeping the action grounded in reality, while simultaneously adding artistic flourishes throughout. Images like a crude effigy of Hitler constructed by displaced villagers, the protagonist wading through a thick bog that threatens to consume him, and a climax that uses historic archival footage edited together in a novel manner, are all tableaus that will stick with audience members long after they see the film.

Bold, poetic, and haunting, it manages to the magnitude of the merciless treatment those unfortunate enough to stand in the German army’s path endured, all while being surprisingly restrained and stopping short of wallowing in nihilism. While not necessarily a particularly unique war story, it’s one that ought to be told and seen because of its historic truth, lest it ever be forgotten and repeated.

3. The Passion of the Christ (Mel Gibson, 2004)

In his four-star review of it, Roger Ebert called Mel Gibson’s vision of Jesus’ torture-filled final hours the most violent film he had ever seen. Save for perhaps fans of Peter Jackson’s tonally dissimilar Braindead, many would likely agree. Topping Entertainment Weekly’s list of the most controversial films ever made, this highly divisive biblical drama broke all kinds of records (it’s still the highest-grossing R-rated film in the U.S.) and sparked international debates about both its shocking levels of onscreen bloodshed and allegations that it was anti-Semitic.

One observation we can objectively make is that it’s astonishing not just that the film didn’t receive the NC-17 (likely because of the identity of the man receiving all that pitiless punishment), but that many well-intentioned religious parents took their young children to see it (something Ebert advised against, for the record).

Every facet of those final twelve hours is shown in graphic (emphasis on graphic) detail, drawing mostly from the Gospels and The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, a book by Anne Catherine Emmerich, an 18th century German nun. Those who complained that the film didn’t concentrate on any miracles (which isn’t completely correct) missed the point – the focus of the film, as stated in the title, was intended to be the “passion,” or suffering and execution, of Jesus.

By that measure, the title is accurate, and the relentless scourging and sickening crucifixion of the Jewish Galilean are rendered in grisly (and Oscar-nominated) makeup effects (the cinematography and score nominations received by Caleb Deschanel and John Debney, respectively, were similarly well-deserved).

Is the film anti-Semitic? That’s up to viewers to decide, though there is a good deal of compelling evidence – not least of which are the later off-screen antics by the film’s troubled director – to build a convincing case that it is. What is less debatable is that no matter what your religion, you’d have to be an unfeeling sociopath not to be moved by the agony simulated (and sometimes not so simulated, unfortunately) in Jim Caviezel’s gruelingly physical performance.

Seen as a beautiful, moving, and inspiring film by its supporters, and a repulsive, sadistic exercise in torture porn by its detractors, Gibson’s self-financed project ultimately succeeded wildly at the box office. Its merits are still argued over to this day, and will likely continue to be for a long time.

2. Irréversible (Gaspar Noé, 2002)

Hundreds walked out and a few fainted at its premiere at Cannes in 2002. An extremely low-frequency hum plays during the opening scenes in an effort to subtly disorient and nauseate the viewer. Spinning, careening camera movements and strobe effects are similarly employed. And we haven’t even touched on the film’s treatment of sex and violence yet…

The story is deceptively simple: Told in reverse chronological order, the film depicts a happy couple (Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel, who were married in real life at the time the film was made) whose idyllic lives are shattered when Bellucci’s character is violently raped by a stranger after leaving a party. Upon finding out what happened, her boyfriend seeks revenge.

This nasty entry in French cinema is basically an attack on the audience throughout, and as such, it is very effective. What it’s not, however, is an exploitation film – the backwards narrative, in effect, challenges us meditate on the morality of attempted revenge rather than delight in it.

The rape scene at the film’s center is unambiguously horrible and not at all brief, having been filmed in one extended, almost entirely motionless take. Not every rape scene needs to be this unendurable and explicit, but it fits both with the film’s deliberately uninhibited style and strikingly direct approach. Like Hitchcock did with Rope and Iñárritu with Birdman, Noé uses long takes intelligently and to great effect here.

The careful use of digital effects is also commendable, as they make the notorious rape scene and the vicious murder that precedes it (or follows it, depending on your perspective) in the gay nightclub aptly named “The Rectum” all the more realistic. Even after the relative chaos of its first half, the film still manages to shock in its last few minutes of comparative peace in a scene that features no discernible acts of horror at all. It’s actually kind of brilliant.

More of a gut-wrenching experience than an entertaining movie, Irréversible is a film whose lurid subject matter serves a greater purpose, and is rewarding in the end… for those who dare to brave it.

1. Requiem for a Dream (Darren Aronofsky, 2000)

The film occupying the #1 slot on this list will surprise few. With the potential to do more good than any PSA if shown in high schools across the country (not that that’s ever going to happen), this adaptation of the novel by Hubert Selby, Jr. follows four interconnected downward spirals into addiction over the course of several months in Brooklyn.

Jennifer Connelly, Jared Leto, and Marlon Wayans are all excellent, but it’s Ellen Burstyn whose Oscar-nominated and heartbreaking performance will stay with you the longest (the take used in an emotional monologue she delivers drifts slightly because the cinematographer was moved to tears while filming it).

Director Darren Aronofsky uses every trick in the book to simulate his ensemble’s collectively awful experience here, from quick-cutting montages to split screens to extreme close-ups to even attaching cameras to the actors for some sequences. Is it all somewhat manipulative? Sure, but who can argue with methods when the results are so damn effective?

All this culminates in one of the most intense climactic sequences of all time (and yes, this is the part that caused no shortage of problems with the MPAA). Add in a now-iconic score composed by Clint Mansell and performed by the Kronos Quartet and you have a small masterpiece.

It might make you swear off anything stronger than aspirin for a week or two, but that just speaks to the influential power of this psychologically complex indie. It has all the fundamentals of a horror movie, but interestingly, the monster here is not specifically drugs, but addiction. As such, the film’s message is only more universally applicable, and as a whole it is, I would argue, the most horrifying non-documentary film ever made outside of the horror genre.

Honorable Mentions (listed alphabetically)

The topic for this list is, of course, highly subjective, so here are 25 more horrifying movies that almost (but didn’t quite) make the cut:

Amistad (Steven Spielberg, 1997)

Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012)

The Believer (Henry Bean, 2001)

Blindness (Fernando Meirelles, 2008)

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Contagion (Steven Soderbergh, 2011)

Dancer in the Dark (Lars von Trier, 2000)

Dogtooth (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2010)

Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

Fat Girl (Catherine Breillat, 2001)

Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988)

The Green Mile (Frank Darabont, 1999)

I Stand Alone (Gaspar Noé, 1998)

Ichi the Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001)

Kids (Larry Clark, 1995)

The Killing Fields (Roland Joffé, 1984)

The Road (John Hillcoat, 2009)

Seven Beauties (Lina Wertmüller, 1976)

The Seventh Continent (Michael Haneke, 1989)

The Snowtown Murders (Justin Kurzel, 2011)

Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, 1970)

The Stanford Prison Experiment (Kyle Patrick Alvarez, 2015)

Taxidermia (György Pálfi, 2006)

Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971)

The Whistleblower (Larysa Kondracki, 2010)