Kurt Cobain once famously said that “punk rock is freedom.” By this, he meant that divorced from the dogma of mainstream rock, he was free to express himself however he wished, however odd or shocking that expression may well have been. This, evidently, helped him to keep his work intensely personal.

If there is one genre in film in which it can be said that the filmmaker has that same freedom, it surely must be the Indie Genre.

An Indie film can be whatever it wants, or indeed needs, to be. Indie films are not intended to break box office records, though many have surprised us. Divorced from the compulsive need to sell the movie as many people as possible, the directors, screenwriters, and actors have the freedom to make their choices for the sake of art rather than commerce. In doing this, they are often likely to shock, break from type, infuriate, or inspire; but they are truly free.

Here are 30 great Indie landmark that have graced our screens since 1990. If the 1990s was the golden age of the Independent movie, then this list may well represent by association the finest films from the Golden Age of the Independent Film. You may agree or disagree, there may well be films that you believe this list has overlooked. There may also be films that you deem unworthy of such a profound title.

But, suffice to say, not one of these 30 films compromised their message. For better or worse, they are each unashamedly individual. As such, none should go unseen by any modern cinephile.

30. Dead Man (1995)

A wandering, sprawling, largely plotless epic, Dead Man seems to have been born of the cult ideal like few others. But then, what else is to be expected from a pairing of Johnny Depp and director Jim Jarmusch?

A morbid, mordant film, its protagonist William Blake (it is not quite established whether or not he is the William Blake) is doomed from the beginning by virtue of the film’s very title; not to mention a jealous husband’s gun shot. The film is about the journey into another life, and the attempt to find yourself in the process.

Pursued through the forest and with only a Native American spirit guide for company, there is much strangeness awaiting Blake over many chance encounters, not to mention some not so chanced ones. A vicious gang includes a grizzled cross dresser, a hitman crushes a man’s skull.

Yet, the film is oddly peaceful. A trip across a river finds a deeply spiritual journey through an Native American town, and towards the end in more ways than one. Was this the real world? Was it the afterlife? Does it matter? Food for thought, indeed.

29. Rushmore (1998)

When history looks back at the great one liners of Bill Murray, it is unlikely that “She was my Rushmore, Max” will make the list. Though, as fans of Wes Anderson’s first quintessentially Anderson-esque film will quickly tell you, that is the list’s loss. This is the film that discovered Jason Schwartzman, not to mention potentially being the main instigation behind the revival of Bill Murray’s career.

In teenage protagonist Max Fisher (Schwartzman), we find one of cinema’s memorable dreamers, and one of cinema’s memorable schemers. What defines Max is that he is, as an opening fantasy sequence will inform you, distinctly unremarkable.

He has no particular skill or distinction, his performances on the school wrestling team, in fights with other students, and as a playwright are all merely admirable blunders of youth. Yet, Max carries himself with grace and charm like a man who truly owns the world around him.

The story of barber’s son Max and unhappy millionaire Herman Blume and how they fight over the same woman, Max’s teacher Rosemary Cross, is a long and serendipitous one. The story both embodies and defies coming of age film conventions, with resolution found but nobody quite ever saving the day.

Watching Max continue to wear his private school uniform, despite now attending public school is both funny and tragic, as is Bill Murray sinking to the bottom of his back yard pool as his wife flirts with another man to little chagrin. In the end, as we listen to “Ooh La La” by The Faces, one feels that the anthem’s use has been earned.

28. The Blair Witch Project (1999)

In terms of success yielded in the absence of studio funding, The Blair Witch Project is both the definitive indie film of the 1990s and, financially speaking, the greatest independent film success of all time. The production was independent in the most literal sense of the world.

In essence, filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Bob Griffin took semi professional actors Heather Donahue, Michael Williams, and Joshua Leonard into the woods and terrorized them by night as they attempted to react in character as student filmmakers there to make a documentary about the local legend of the Blair Witch. perhaps the only thing more remarkable than the film’s financial success is the fact that many members of the public actually bought the rumour that was brilliantly hatched by the film’s marketers- that the events were real.

A victory of marketing indeed, but there are chilling moments in this admittedly repetitive film. Though the characters wander and circle by day, the night terrors are eerily real, a trait heightened by the film’s Hi 8 video photography. Heather Donaghue is great also, particularly in the much parodied handicam confession, mucous shamelessly emanating from her nose as she weeps in terror at her worsening fate.

Today the choice of self-held angle on this sequence would quickly be labelled a “selfie”, but there was no such inspiration then. In the end, for a film often decried as extended marketing gimmick, many a skeptic have admitted that the final scene is about as chilling as horror gets.

27. Broken Flowers (2005)

An ageing Don Juan receives a pink letter informing him that he is a father. But from who? And who is the son? This is one of the strangest movies ever to be played dead straight. It is just as well, then, that director Jim Jarmusch cast the deadpan comedy guru Bill Murray, fresh off a career revival, as his leading man. What follows is a detective story that feels more like a window into the wreckage of an old rogue’s past.

Thankfully, the characters are played straight as Murray’s Don Johnson. The promiscuous ex and her voyeuristic daughter, the jealous lesbian lover, the loveless upper class marriage, the irate biker chick, the characters that Don meets on his journey of investigation into his past become apt incites into various break-ups of Don’s, not to mention the human condition in general.

Of course, there are plenty of signs of Jarmusch’s odd take on humanity. The sleuth-obsessed neighbour of Don makes him an odd mix cd to play on his voyage, one which periodically keeps the tone of the film somewhat surreal. As does Don’s inexplicable decision to wear only Adidas training attire. But, as witnessed by a graveside visit by Don to a perished ex, the humanity of this film tends to admirably overpower any indie contrivement. This comes as good news in a film that prides questions over answers.

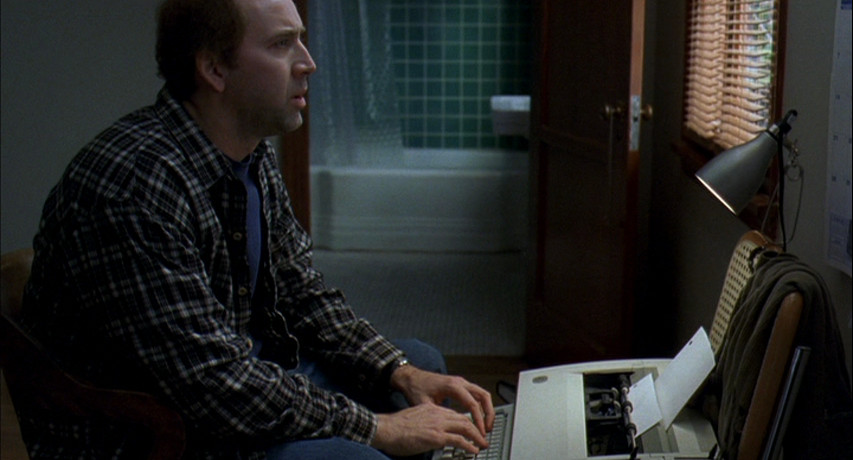

26. Adaptation (2002)

This film is a curious, era transcending, meta-fiction puzzle that nonetheless charms and oozes both the best and worst of the human condition. In the film, Charlie Kaufman writes himself into the lead role (albeit portrayed by Nicolas Cage).

The plot finds Charlie in the wake of writing being John Malkovich, but still plagued by doubt and writer’s block. As he tries to adhere to his artistic principles whilst adapting a book on horticulture, he learns that his oafish brother Donald has found ironically success with his seemingly hack screenplay. Murder, sex, lies, and condescension ensues.

The chemistry between Meryl Streep and Chris Cooper is magnetic, as is the performance of Cara Seymour as Amelia, but the film’s true chemistry lies with Nicolas Cage playing opposite himself.

Loveable simpleton Donald and neurotic Charlie are polar opposites, but the affection between them bubbles to the surface by the end and strengthens the film’s occasional montage experimentation. The film’s originality and visual splendor may lure its fans at the onset but, by the end, the film’s empathy may be its abiding characteristic.

25. In the Bedroom (2001)

A suburban tragedy from Todd Field, we have a tale best described by its fans as a story of escalating serendipity.

The film is also a worthy entry into the unlikely vigilante canon, as murder and revenge abounds in what initially appears like it may be simply a kitchen sink melodrama. The fact that the vigilante element gels admirably with the romantic elements is a credit to both the script and the tactful storytelling of Todd Field, as well as a tremendous ensemble cast that include Sissy Spacek, Marisa Tomei, Nick Stahl, and Tom Wilkinson.

The story of a young man who begins a romance with an older woman and a middle aged man who seeks vengeance for his murdered son is told in a realist vein, but the stylistic flourishes are present also.

The photography is quite breathtaking, and there are fascinating editing techniques at play such as the match cut and montage rhythms to please the purist. Most importantly for the films devotees, the final scene is left open to moral assessment. The viewer is left to decide whether or not anybody’s actions were truly justified.

24. Blue Valentine (2010)

Blue Valentine should be mandatory viewing to all those hoping to marry in the immediate future. Not because it is overly cynical, nor overly saccharine. Indeed, the film’s abiding quality is rather admirable in any film, it feels real. For a medium that deals in glamarous actors, gorgeous canvases, and the dialogue and scenarios of professional writers, authenticity is a rare quality that many films strive for, but that most miss. Blue Valentine has all the aforementioned glamour and rich staging, yet it manages to transcend them and feel very real in many of its extended sequences.

A violent beating is unedited and graphic, people using elderly relatives as a ploy to get dates, families fighting over breakfast, bumping into an ex at a convenience store. All of these moments resonate with the kind of authenticity of improvisation and impromptu staging. In particular an extended sequence in which the central couple of the film fall apart in a sleazy theme motel is agonizing. Over the course of resentment, bad sex, career argument, and long entrenched bitterness, the scene may resound as frighteningly for the viewer as anything in the horror genre.

Still, the movie’s foremost moment of authenticity comes when Ryan Gosling’s Dean plays his beloved Cindy (Michelle Williams) the song “You and Me” by Penny and the Quarters. Dean has proposed the song to be their special song due to its originality and lack of exposure. Cindy’s reaction to the song is earthy, sensual, and impromptu.

One detail that is fascinating to note is that actress Michelle Williams had genuinely never heard the song before shooting the scene, and was not aware what song Ryan Gosling was to play for her. This was re-planned by the actors and director Derek Cianfrance. Her enthused reaction is, thus, not acting. Not a bad strategy for a film that strives to strike upon the truth at all cost.