15. Before Sunset (2004)

Simply to attempt a sequel to one of the most structurally courageous romantic films of all time, 1995’s Before Sunrise, was a courageous task. To have it be even more structurally stubborn as its predecessor magnified the risk even more so.

However, for director Richard Linklater and actors Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, to revisit the characters of Jesse and Celine was fate and, as such, essential. Nine years on, we find Jesse and Celine in Paris, reunited after their first and only meeting at Jesse’s book signing. The book is based on his one night only romantic triste- so their second meeting is as such somewhat of an unusual one.

Yes, this film is 85 minutes of two people talking, with little to no narrative intervention. However, for fans of this franchise, this installment could not be more urgent. Now in their thirties, Celine is alone and Jesse is caught in a loveless marriage. With Jesse due to fly out of Paris in the evening, Jesse and Celine have one afternoon in which to decide whether or not to spend the rest of their lives together, or part once more and forever hold their peace.

This urgency adds a depth and power to the wandering premise, and the characters slight melancholy air makes the film more powerful than the first. The end will have you virtually reeling, the idea of and meaning of love ruminating in your head long after.

14. Under the Skin (2013)

If 2001: A Space Odyssey had been intent on being a character study, it may well have looked and felt something like Under the Skin. An odyssean structure, obtuse and startling visual communication, unanswered questions (who or what is the man on the motorbike?), and much mystery abounds in this curious sci-fi enigma. Laura (Scarlett Johansson) is on the prowl, but the reason, both cause and effect are not totally apparent.

The film begins with somewhat of a methodical birthing sequence. We the witness Laura charming and seducing wittless strangers on the streets of Glasgow. Their incredulous reactions are genuine- director Jonathan Glazer chose to record real people on the street, oblivious to the fact that they are appearing in a major feature film. Odd? We haven’t even touched upon the murder scenes. Laura is an alien, this is apparent, much of the rest is left up to you, as this is a film that gives you just enough information to stay afloat, but not enough to spoil its mystery.

Johansson holds the visual trickery together, reiterating her presence at all times and anchoring the oddness with soul. She is wicked, curious and, in time, vulnerable. You want to know what she is thinking during those early scenes of stalking and conquest. You want to know why she thinks it. Is she good? Is she bad? Either way, it is difficult not to feel empathy in the films conclusion. There may even be a touch of social commentary to be found in those dark, barren woods.

13. Barton Fink (1991)

Born out of writers block, and as stubbornly indefinable as any film you are ever likely to see, this is really a film for artists by artists. The remarkable aspect of this film is perhaps that it succeeds without distinct genre or storytelling convention of any kind. Barton Fink (John Turturro) is a man who lacks glamour in a glamorous town.

Assigned as the script writer on a hack wrestling film in Hollywood, he mourns for the stage and his artistic integrity back home. His gloomy, cavernous motel room is his only fitting abode in Tinseltown. There he meets the charismatic but oafish Charlie Meadows (John Goodman). With only Charlie to report to, Barton falls slowly into madness in the caverns of both his room and his mind.

Of course, there are a few McGuffins to drive us forward. There is a girl of interest to Barton, in the form Of Judy Davis’s repressed housewife Audrey. Her husband WP Mayhew, played by John Mahoney, is a terrifying cautionary tale for Barton as a respected author who has fallen into an alcoholic stupor.

Of course, we come to expect Barton to follow. Given the Coen Brothers resume, it comes as little surprise that things continue to get increasingly grim, and morbidity and death soon follow nicely. As such, this could be a rather frightening movie to show the budding writer in your life.

12. Dogville (2003)

An audacious film, Dogville is quickly earning acclaim as one of the bravest indie films of the 2000s. Furthermore, it is truly fascinating. Over the film’s near three hour running time, we are presented with a litany of moral conundrums, “what would you do?” questions that resonate on a most human of levels.

The protagonist, Grace, arrives in the sleepy town of Dogville whilst on the run from dangerous criminals. She brings out the best in her love interest Tom, but slowly brings out more and more of the worst in the villagers who begin to take advantage of, then persecute her in increasingly disturbing fashion. Sound interesting? How about if I tell you there are no sets, just a sound stage with chalk outlines?

Spending three hours in the hand-drawn imaginary town of Dogville is more cinematic than you might think. The ensemble cast is hugely impressive, boasting the likes of Stellan Skarsgard, Lauren Bacall, James Caan, John Hurt, and Philip Baker Hall. The hand held camera makes terrific use of the Altman-esque zoom and pan approach to capture the action in immediate fashion.

Then, there is the ending, which will give any vintage James Cagney caper a true run for it’s money. It is a brutal, stylish, and oddly hysterical finale that finds an unexpected musical contribution. Indeed, Dogville is entirely too fascinating to miss.

11. Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

When Paul Thomas Anderson announced at Cannes that his next film would be a romantic comedy with Adam Sandler, the announcement was met with laughter from a crowd that assumed Anderson to be speaking in jest. Yet, Anderson had a curiosity for both Sandler and the romantic comedy that he could not resist.

So, the film transpired, and the result was extraordinary indeed. Punch Drunk Love is deceptively breezy. Yes, the film is a romantic comedy. However, its gentle pace, dreamy music, its lead actor, and the film’s premise deceptively hides neurosis, sadness, and even violence buried just under the surface.

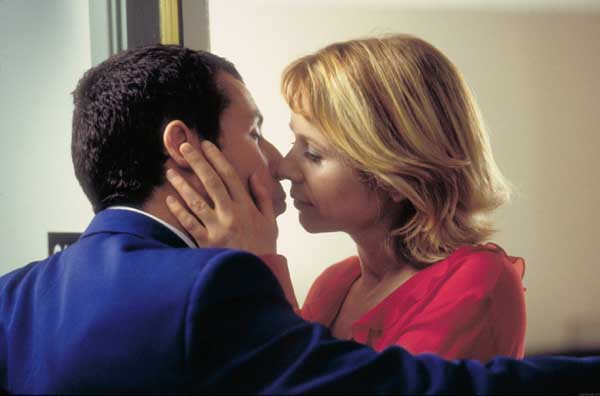

Barry Egan is a thirty-something misfit with seven sisters and no girlfriend. He runs his own plunger manufacture business. It is a conventional premise, but from the onset things get unfamiliar. There are phone sex lines, harmoniums, blackmail threats, and room thrashings. To see these odd events, all told through the innocence of Barry and his love interest Lena (Emily Watson) is striking.

One particular scene involves Barry running and leaping to escape some thugs, all told through the gentle long shots associated with the romance genre. Striking too is Barry’s bright blue suit in contrast to Lena’s red dress, casting them both as outcasts. These are outcasts you can learn to care for, resulting in Adam Sandler’s brief moment in the critical favor.

10. Melancholia (2011)

If the sight of Kirsten Dunst nude in the dead of night, lying under and worshiping the coldness of the Moon isn’t typical of Lars Von Trier, I don’t what is. Few but Von Trier would deal with the difficult subject of depression in as lofty a manner as this, which to many is nothing short of endearing. Impending apocalypse cannot be an easy thing to deal with and, as the planet Melancholia crashes towards Earth, Justine (Kirsten Dunst) who is nihilistic from a life of depression, her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsburg) who is warm and fond,

Claire’s innocent son, and cynical husband John (Kiefer Sutherland), all await their doom. We learn how their characters deal with the worst and, in turn, are conveyed many interesting observations on humanity. Claire’s section of the film ends with the film’s conclusion-spectacularly.

More surprising still, however, is the first half of the film, Justine’s story. Why is this section surprising? Well, because there is hardly any reference to the apocalypse at all. Instead, this section deals with Justine’s dismal attempt at marriage to her fiance Michael. It is during the wedding that we truly learn about these characters.

Justine’s self-destruction is the least of their worries. A cold Mother, a vagabond father, and a hysterically cruel employer (brilliantly played by Stellan Saarsgard) are all part and parcel of the tragedy. In many ways, Von Trier is able to make these moments of brazen humanity in every nuance as devastating as the apocalypse. This is some feat. As Justine collapses with despair, the viewer may well feel the same.

9. Boyhood (2014)

Finally, for those who still require evidence of the worth of the last 5 years in cinema, look no further.

Boyhood is not just compelling, nor is it simply entertaining, though it is both of those things to be sure. Yet, Boyhood is more, it is a landmark. the film was shot over only a few weeks, weeks that were stretched out intermittently over a period of 12 years. The same cast would return for a week or two each year to film. They performed this sacred ritual of trust and creativity from 2001 to 2013. The final result, released in August 2014, is something truly remarkable.

Remarkably, we witness young Ellar Coltrane and Lorelei Linklater, playing siblings Mason and Samantha respectively, grow from children into young adults over the course of three highly immersive hours. Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette evolve as divorced parents too, through copious partners, marriages, additional children, acrimony and peace. This is not so much a film about a family as it is an invitation for the viewer to join a family.

By the way, it is a great film, too. Ethan Hawke is sensational as the Dad who refuses to submit to middle age, forever wearing his youthful rebellion on his sleeve, even when eventually somewhat tamed. Patricia Arquette’s Mom weathers a frightening storm of bad relationships to self destructive alcoholics, she stands as a great insight into the capacity of people to repeat self destructive patterns.

Still, the cornerstone of the film is Ellar Coltrane as Mason. Mason is sweet, he is obnoxious, he is brave. he is selfish, he is everything the story asks of him. He plays Mason with skill, but with a level of naturalism that still feels as though he may not even be acting. He hits each note so effortlessly that each scene feels half remembered from our own adolescence. So many characters come and go from his life, and his attitudes, views, and capabilities age gradually over the lengthy runtime as they did for all of us. Boyhood is Mason’s story, Boyhood is our story. Moreover, Boyhood is quite an indie film.

8. Buffalo 66 (1998)

The film in which the notorious Vincent Gallo finally decided to show us his soft side is also one of the most stylistically assured works of auteurship you will see post Goddard. All of the Indie Film tools are present- split screens, breaches of continuity, breaking the fourth wall, scenes which break from realism- Gallo pulls out all of the stops as stylistically indulgent filmmaker.

In short, Buffalo 66 is so overtly indie it almost borderlines on parody. Thanks to Gallo and co-star Christina Ricci, however, this is not necessarily a bad thing.

Beyond the stylistic flourishes, the most remarkable aspect of this film is its sweetness. Gallo makes a kidnapping story truly romantic, no small feet. In turn, he also makes both victim and perpetrator of said kidnapping equally empathetic. Gallo plays Billy as a juvenile rather than a violent sadist, and Ricci plays Layla as anything but a one dimensional victim. In the end, for all of the bombastic style, Gallo raving in a doughnut shop about his new girlfriend may well be the highlight.