15. The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985)

Exploring the ways in which movies interact with “real” life via surreal farce is part of the light appeal to Woody Allen’s surprising comedy adventure The Purple Rose of Cairo.

Cecilia (Mia Farrow) is a fragile, wistful hash-house waitress trapped in a dead-end job and an abusive relationship with an undeserving, two-timing a-hole of a husband (Danny Aiello). Cecilia finds escape as an avid moviegoer at the Jewel Theater where she’s particularly drawn to this week’s latest adventure feature, “The Purple Rose of Cairo” and one of its stars, the handsome Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels).

Cecelia watches the film again and again when suddenly, and improbably, Tom steps right out of the film to join her in the real world. As the film unfolds, Cecelia is pursued not just by Tom but by Gil Shepard (Daniels, again), the actor who portrays Tom, and equal portions of hilarity, heartbreak, and nostalgic inflection arise. Considered, particularly by European critics, to be one of Allen’s more surreal and sweet showpieces, it’s a magical and courageous film, and a sterling example of his work.

14. Possession (1981)

Andrzej Zulawski’s early 80’s horror film, Possession, has a farfetchedness that may prevent some viewers from giving in to the sublime and startling undertow of feeling and fright contained therein, and that’s a real shame. Possession is, on the surface, a straight-up horror film about a married couple, Mark and Anna (Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani), in the throes of a divorce.

As Anna’s behaviour degenerates into wildly erratic tantrums and manic, compulsive behaviour, Mark meets another woman, Helen (also played by Adjani), a dead ringer for Anna except for her green eyes and halcyon, harmonious presence.

As Possession unfurls, the situations escalate, often disturbingly, and with many shocks and violent prods. Occult elements appear, deepening and darkening the tale, and Adjani’s performance is equal parts alarming and impressive — it may be her finest role — making for a psychological charade that is impossible to predict, vivid, rich, and nerve-rattling in all the right ways.

13. Black Swan (2010)

Darren Aronofsky’s finest film, Black Swan is a dark, dirge-like thriller pitting two ballerinas, Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman, who deservedly won an Oscar) and Lily (Mila Kunis, also excellent), as rivals during a tumultuous production of Tchaikovsky’s highly-esteemed ballet, Swan Lake.

It’s a sweeping, creepy, and disconcerting film, chronicling, amongst other themes, descent into madness, stifled femininity, patrist desires, mental and physical fatigue, and much more.

There is considerable melodrama, too, and perhaps some calculable and regrettable clichés, of the type often found in formulaic competition films, but the dizzying cinematography and peerless performances make it easy to forgive any shortcomings of story, Aronofsky articulates and captures a thematically dense and illusory film of darkness, identity, duality, and divine will. On a visual and intuitive level, Black Swan bends the throttle.

12. The Prestige (2006)

A fine yet flawed, and wholly rejuvenating film for Christopher Nolan — he filmed it between mega-budgeted Batman blockbusters — The Prestige is a playful, at times pretentious, period film set at the ass-end of the 19th century, in London, as two rival magicians continually try to outfox the other.

Hugh Jackman portrays aristocratic illusionist Robert Angier and Christian Bale is the vying blue-collar magician Alfred Borden, and the two are locked in creating the best stage illusion, forever putting them at odds.

Smoke, mirrors, and time manipulating aside (wherein lies the doppelgänger motif, no spoilers here as to how it unrolls), the biggest strengths to The Prestige lay in the exquisite period details and designs (Kevin Kavanaugh’s art direction is immaculate) not to mention some truly inspired casting (David Bowie as Nikola Tesla may be the casting coup of the century!). But, like all of Nolan’s work, it’s overwrought and so much of it hinges on a final reveal that may be too much for the scrupulous viewer.

11. It Follows (2014)

Much of David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows, on the surface an old school horror film, seems to rapturously worship at the paired altars of John Carpenter and Wes Craven.

But Mitchell is decidedly more forward looking than those two respectable genre masters, offering a more keenly observed study of what scares us, one that has a firmer grasp on sexual politics and feminist philosophy – which is bracing in that it’s so absent in most films of this order – and one inflected with nostalgia along with so much angst-fuelled self-reproach and artfully ill-lit dismay.

Maika Monroe gives a breakout performance as Jay, our set upon heroine who does battle with a sexually transmitted curse that gloms onto a shape-shifting entity, a follower, that takes many forms, often a doppelgänger, always mute, and invariably relentless in its hunt.

Well served by Disasterpiece’s synth-driven score — which perfectly recalls Goblin’s compelling compositions for Dario Argento — and the derelict and run-down streets of Detroit, rife with urban decay, It Follows is a spine-chilling dissertation on supernatural manifestations, raising alarms, and announcing the arrival of a new genre standard.

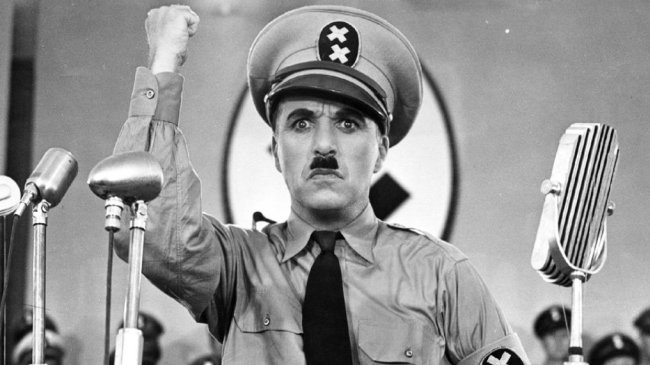

10. The Great Dictator (1940)

Charlie Chaplin’s most personal and polemical film, and his very first with sound, The Great Dictator may well be his chef d’oeuvre. Released near the outset of World War II, filmed as the world was on the brink, Chaplin pointedly and purposely chose to draw parallels between his famous Tramp character and the Führer himself, Adolf Hitler. While Chaplin popularized the toothbrush moustache, Hitler demonized it, but that’s a moot point now.

Chaplin plays two roles; a Jewish barber, never-named, and dictator Adenoid Hynkel. His lovable and recognized persona is apparent in the barber, who is mistaken for Adenoid, and whose explicit anti-Semitism and other boorish traits may seem somewhat naïve through a modern lens – Chaplin and the rest of the world would no nothing of “The Final Solution” for a number of years yet – was and is an act of fire-eating in the face of corruptive evil.

A powerful film, full of cathartic comedy, the closing speech, the first time Chaplin ever addressed the camera and spoke, is a moving, forcible, and persuasive plea for peace, made at a time when the world needed to hear it. The world still does, and The Great Dictator is a testament towards sympathy, understanding, amity, and the curative powers of laughter.

9. Body Double (1984)

Body Double is vintage Brian De Palma at his subversive, sleekest, and trashiest best. Toying with familiar Hitchcockian themes of voyeurism and obsession — sure, both Rear Window and Vertigo are mercilessly mined — the resulting erotically-charged thriller is a full-tilt charge of ghoulish glee.

Buttressed by a fearless performance from Melanie Griffith as porn star Holly Body, 80’s cinema was seldom so smart ass and enterprising. Holly finds herself the fascination of failed actor and agoraphobe Jake Scully (Craig Wasson, oozing barely-tempered sleaze), who thinks maybe he’s been spying on Holly, maybe even witnessing her murder, from afar during a house-sitting gig at a pal’s fabulously fresh and modern Hollywood Hills home.

The subsequent mystery, full of twists, turns, incredulity and intrigue, is a master class in misleads, narrative leaps, flashbacks, panache and put-ons in an airtight plot that’s full of deceit. Body Double is an intoxicating, and capricious caper that joyously goes too far, and even breaks new, albeit sticky, ground.

8. Mulholland Drive (2001)

For all its dark detours, and there are many, David Lynch manages to break chains of anguish and upset with odd ecstatic ardor, capturing, so often, a world of ravaged sensitivity with Mulholland Drive.

Notably with this film, Lynch has handed Naomi Watts’ her first major role — which she knocks out of the proverbial park — one she embraces with an operatic élan of emotional extremes. Never before has Lynch’s dream logic been so ecstatically displayed and with such mind-shredding results.

A neo-noir mystery which, at times, feels like a subversive Nancy Drew-style yarn, the wholesome Betty Elms (Watts) newly arrives in L.A., plans to breakout into acting, despite her extreme, almost comical naiveté. Betty soon meets Rita (Laura Harring), with whom she becomes fast friends and roomies, oh, and there’s Diane (Watts), a waitress, who looks just like Betty, amongst others in a Lynchian chorus of late-night and sun-soaked chimera-like characters.

An often upsetting film, anxieties and fears accumulate in staccato sequences rendered in punishing tableaux, begging the question: is what we’re seeing Betty/Diane’s death dream? Perhaps a better question is who’s-dreaming-who?

Mulholland Drive offers up sublimated desires, dual identities and Hollywood satire in a package that may well be David Lynch’s finest work, or his most irksome, depending who you ask. Regardless of this, the dreamlike wanderings, intense imagery, comic sidesteps, and eerie instances certainly add up to an rememberable puzzle with alternate realities, danger, provocation, and strange shadows. It’s something of a pièce de résistance, whether the viewer wants it to be or not.