15. Experimenter

Michael Almereyda, USA

A visually and verbally spellbinding showpiece from Michael Almereyda (Nadja), Experimenter is set in 1961 at Yale, as renowned social psychologist Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard) wields the baton on a series of psychological experiments. Curiously structured with chronological to and fro, fourth wall asides, arcs and eddies into surrealism, Almereyda still manages to present his treatise with an amenable charm.

Experimenter is an old school indie arthouse homecoming, and a bracing tonic of a film. Like Louis Malle’s My Dinner With Andre, this is a film that haunts and hypnotizes, sending the audience away changed, troubled, reeling, and utterly impressed.

14. High-Rise

Ben Wheatley, UK

British firebrand Ben Wheatley (Kill List) adapts J.G. Ballard’s (Crash) skyscraping novel High-Rise, knowing full well the risks involved in raising such a structure. Set in Thatcher’s England, 1975, the denizens of a 40-storey luxury building will, over the course of three scant months, revert to ferocious barbarity, explore Freudian textbook extremes, and propound poetic self-destruction as Wheatley unleashes the beast.

Visually disturbing and hard-boiled vintage soon spurs an absurd cinematic carnival of arraigned values, hamster cage clichés, standing aphorisms, and more. Drugging, boozing, orgies, beatings, lootings, rape, and murder all soon ensue.

As High-Rise grows progressively uncivilized and brutal it also becomes more and more hypnagogic, the boldface emblems of politics, the gallows humor with a social conscience, they all blur into a gloriously downbeat pageant, and a tour de force from a fearless filmmaker.

13. The Lobster

Yorgos Lanthimos, Ireland/UK/Greece/France/Netherlands

Marked by merry invention, The Lobster manages many a dark detour in its drive down contentious cobblestones of social mores, dating rituals, courtship protocols and group polemic. Greek auteur Yorgos Lanthimos’ (Dogtooth) latest absurdist allegory is a distinct dystopian satire steeped in narrative tension.

The Lobster gets its epithet from its conscience-stricken central character, David (Colin Farrell), who has chosen the marine crustacean as the animal he will become if, after 45 days at the hotel resort he’s staying at, he hasn’t found a mate.

On this strange premise hangs Lanthimos’ strange, bleakly comedic tale, rich with a Samuel Beckett-like absurdism along with elements of the Théâtre du Grand-Guignol, and a significant fracturing of mimesis that doesn’t hollow out the efforts of The Lobster as a poignant love story.

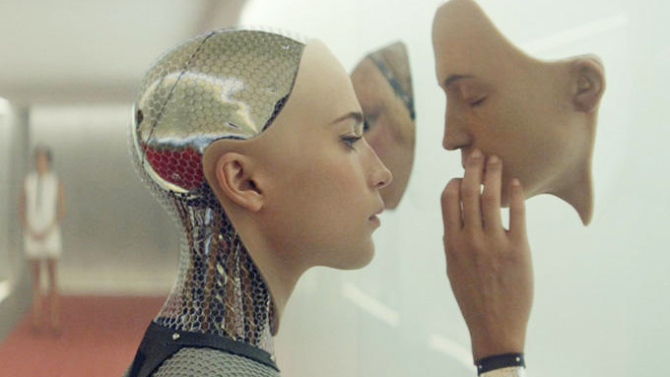

12. Ex Machina

Alex Garland, USA

Alex Garland, whose screenwriting credits include 28 Days Later, and Never Let Me Go, cut his director teeth with another script of his, the speculative fiction Ex Machina. Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) is a programmer for a search engine called Bluebook, who’s illusive CEO, Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac) has assigned him to a lucrative new project involving artificial intelligence in the form of Ava (Alicia Vikander, brilliant).

Despite the limitations that come with a chamber piece, and Ex Machina is structured as such, the film not only dissects grand ideas, it details how people behave when they know they are being watched, and, best of all, articulates a dystopia that’s charitable towards AI but as for humanity? Well, we might just be fucked, let’s put it that way.

11. Son of Saul

László Nemes, Hungary

Much to director/screenwriter László Nemes credit, he eschews all the usual Holocaust drama clichés in his heart-rending and brutal debut, Son of Saul.

Saul (Géza Röhrig) is a Hungarian Jew forced to help the Nazis in Auschwitz where he is a Sonderkommando – concentration camp workers made up of prisoners – whose hellish charge is burning the dead.

Muscular long takes are intricately choreographed in ways that often obscure the focus, causing fright, uncertainty, and anxiousness in the viewer. Harrowing sequence follows harrowing sequence, making for a gut-wrenching experience as well as a masterclass in formalist technique.

As Son of Saul moves inexorably towards a gruelling finish, it requires such intense tenacity that we understand, maybe fleetingly, the endurance and bravery of broken men. Unforgettable.

10. Hard To Be a God

Aleksei German, Czech Republic/Russia

A medieval sci-fi epic adapted from the deeply imaginative novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky – their book “Roadside Picnic” was the basis for Tarkovsky’s Stalker – from director Aleksei German (My Friend Ivan Lapshin) was a years-in-the-making labor of love that amounts to a breathtakingly unforgettable film of brutal savagery and painful sympathy.

A team of sub-rosa scientists from Earth are on an alien planet, Arkanar, similar to our own but where the Renaissance never occurred, leaving the populace in a savage and decaying Middle Ages without end.

German’s pet project for decades, he first adapted Hard To Be a God for the screen in the late 1960s, and filming didn’t begin until 2000.

Principal photography lasted until 2006, and the editing ran for years, until German’s death in 2013 – the sound design was completed by his son – but the results are a meticulously detailed tour de force with lush visuals that echo the religious illustrative narratives of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. An epic in every sense of the word, you’re unlikely to find a more immersive, ingrained and extravagant film than this.

9. Room

Lenny Abrahamson, Canada/Ireland

Five-year-old Jack (an astonishing Jacob Tremblay), who, along with his mother, Joy (Brie Larson, superb), make a soaring exodus from the one-room dungeon they’d been in for over half a decade in Room. Director Lenny Abrahamson (Frank) and screenwriter Emma Donoghue – Room is based off her 2010 novel – tell Jack and Joy’s harrowing story with great diligence and largesse, at once luminously simple, and persistently lyrical.

If it’s essential for a film’s greatness that it contain two or more indelible set-pieces; Room is teeming with them and harbors a moving and dactylic monument to maternal sufferance.

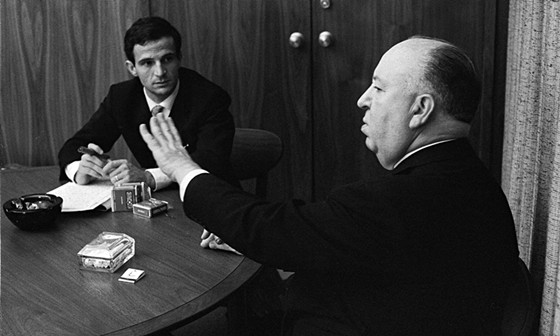

8. Hitchcock/Truffaut

Kent Jones, France/USA

This invigorating documentary from Kent Jones (A Letter to Elia) is a tonic for cineastes of all shades the world over. In 1962 filmmaker and French New Wave founder François Truffaut befriended his hero, Alfred Hitchcock, and interviewed him over an eight day period. The results of the interview was the now classic 1966 tome “Hitchcock/Truffaut”, an inspirational and esteemed standard on creativity, inspiration, art, and life writ large on the silver screen.

Combining a wealth of clips of the titular duo, as well as excited testimony from a huge cross-section of filmmakers (including Olivier Assayas, Wes Anderson, David Fincher, and Martin Scorsese amongst others), Jones manages to capture the treasure trove electricity of Truffaut’s book in an engaging and self-effacing way. This film gave me goosebumps for it’s entire running time and will no doubt be cherished, exhausted, and returned to interminably like the book that inspired it.

More than a legacy and a valentine, Hitchcock/Truffaut is a generous appreciation towards cinema, it’s lore, and it’s legends.