5. Stoker (2013)

Park Chan-wook’s Stoker has an indelible relationship to Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt. It could perhaps be said that the film is a modern re-imagining of the original film. It shares not only thematic and cinematographic similarities, but also narrative and stylistic similarities.

The films shares characters and the concept of the double as a means of a sort of reflection of a person’s unity represented by two different characters. What Park does in terms of expanding on Hitchcock’s original work is that he extrapolates not only upon the psychological consequences of doubling, but also the physical repercussions of jealousy and inter-family conflict.

The film is perhaps a darker take on the nature of humanity to exhibit violence when we encounter psychologically damaging situations. Perhaps, the film is one that Hitchcock would have made himself with access to modern equipment and analysis.

4. Charade (1963)

Stanley Donen’s 1963 film, Charade has been described “the best film Hitchcock never made” and this praise is undoubtedly warranted. The fact that it was contemporaneous with Hitchcock’s most experimental era has coloured the fact that it is tied inextricably to the conventions that still drove Hitchcock, but rather than moving toward the darker and more empathic route that Hitchcock took with his films in the 1960s, Donen attempted to distill the motifs and stylistics which made Hitchcock’s films exemplary into a pure homage of appreciation.

It’s interesting to note the difference in form between Hitchcock’s films of the time and Charade, with Charade representing a movement to recapture the vibrations of Hitchcock’s 50s films in the newer social context of the 60s in a sort of deference to Hitchcock’s 1963 film, The Birds. Hitchcock, at the time was moving from a more concrete depiction of ideas to a more or less abstract form of symbology with his filmmaking in “The Birds”.

The distance Hitchcock put between his later work and his earlier work speaks to his innovation as a filmmaker, but it also speaks to the cultural value of his ideas. Charade itself was more successful than The Birds at the Box Office, which alludes to the shifting tastes of the cinema audience as opposed to the artistic expression of Hitchcock.

In this way, we see that while it is regarded as the “best film Hitchcock never made”, it was nonetheless something of a style that Hitchcock himself moved away from. This doesn’t at all make it a bad film, but rather reflects the way that creators and audiences are at times at odds with one another, and speaks to the collective memory of society when it comes to the impact cinema can have retroactively.

3. Gaslight (1944)

George Cukor’s Gaslight was cut from the same cloth that Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious and Lifeboat were. Using Gas Light as a contemporaneous sibling to Hitchcock’s work at the time, we can see that it could have easily been something that Hitchcock himself would have been interested in directing or adapting.

The film deals with the attempted theft of jewelry, a murder and a romance that buds among the conspiracy which comes to light years later among the death of a mother and the receipt of a mysterious letter. The film also deals with the ramifications of psychological trauma (much in the same way Hitchcock’s films of the time did, with their focus on the effects of anxiety, paranoia and interfamilial relationships).

The film itself was a remake of an original film (produced in 1940) and the difference between both films expresses the burgeoning influence of Hitchcock upon cinema of the time. Cukor was himself a talented filmmaker but comparing his style from The Philadelphia Story in 1940 to Gaslight in 1944 does indeed illustrate the growing impact of Hitchcock as a filmic stylist and provocateur.

Gaslight itself owes a debt to Hitchcock in that Cukor, possibly influenced by Hitchcock’s contemporary films, tried to re-arrange the drama pieces as paranoid and inexplicable dream-like events that become meditations on the indistinct separation between reality and one’s impressions thereof.

In this way, it’s possible that Cukor was attempting to challenge Hitchcock by creating a film so indistinguishable from Hitchcock’s own style that Cukor sought to make his place in the industry. It’s worth mentioning that Cukor and Hitchcock were acquaintances and that it’s possible a friendly rivalry existed (possibly pushing Hitchcock to attempt crafting black comedies in the vain of Cukor).

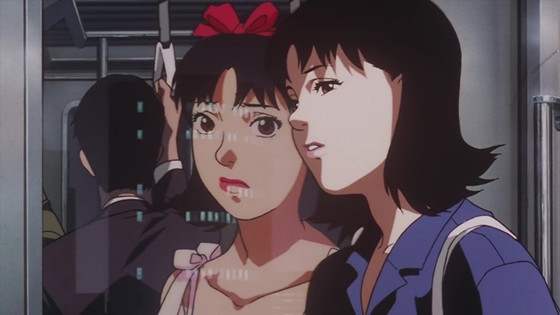

2. Perfect Blue (1997)

Satoshi Kon was a noted admirer of Hitchcock, with Kon noting several of Hitchcock’s films as among his favorite films. He never directly tied Perfect Blue to Hitchcock particularly, however there are various similarities between Perfect Blue and many of Hitchcock’s films (most evidently Vertigo, Psycho and Rope).

Hitchcock’s use of reality v. perception as well as his conspiratorial thematic obsessions are evidenced through Perfect Blue, as Mima (voiced by Junko Iwao/Ruby Marlowe) becomes increasingly disoriented and cannot distinguish her performances from her life off-stage.

As her stalker progressively attempt to appropriate her identity, Mima is psychologically traumatised to the point of dissociation, which is another favored dynamic of Hitchcock’s. In this way, Kon uses this methodology to further a narrative of suspicion, with the audience attempting to discern the reality of the film’s narrative as opposed to the supposed truth that is concealed within the mysteries and conspiracies.

Like Mima, and like many of Hitchcock’s protagonists we become entranced with the fabrications of our perceptions and begin to question our own beliefs and truths. Kon is as masterful as Hitchcock in his subversion of expectation, which is made all the more compelling with Kon’s understanding of Hitchcockian narrative subterfuge and manipulation of an audience’s understanding. They were both magicians of cinema, using misdirection to lead an observer through the mazes of their creation.

1. Diabolique (1955)

Diabolique is perhaps the best example of a great film that Hitchcock never made in the sense that Hitchcock himself actually wanted to direct the film. After a bidding war for the screen rights to the novel She Was No More by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, Hitchcock was blocked from directing the adaptation by the director, Henri-Georges Clouzot, also known for 1953’s The Wages of Fear.

The film departs somewhat from a traditional Hitchcockian narrative in that it combines aspects from both the psychological thriller genre and the horror genre Clouzot, like Hitchcock, had an ability to meld genres into a composite while having aspects of both integrate so perfectly that the combination was not detrimental to its composite pieces.

Throughout the film, like many of Hitchcock’s, there underlies a foreboding feeling of suspicion and paranoia along with a dissonance, where the audiences is placed in the position of believing the narrative as it is or perhaps scrutinizing what they are being told.

Most evocative was Clouzot’s inclusion of a title at the end of the film asking the audience not to spoil the ending, which as a construct in of itself speaks to Clouzot’s knowledge of deception and narrative creation. Perhaps the film would have been different if Hitchcock himself had directed the film, but it is not in dispute that Clouzot was well aware of Hitchcock’s influence and perhaps intended to position himself as an alternative to Hitchcock’s artistic method.

If that was the case, Clouzot succeeded greatly in creating one of the most provocative and interesting cases for an alternative to Hitchcock, it truly is one of the best films that Hitchcock did not make.

Author Bio: Alan is a writer, musician and composer from Calgary, Canada. His short fiction has been previously published in L’Allure des Mots out of Miami FL. His music can be found on Spotify and iTunes.