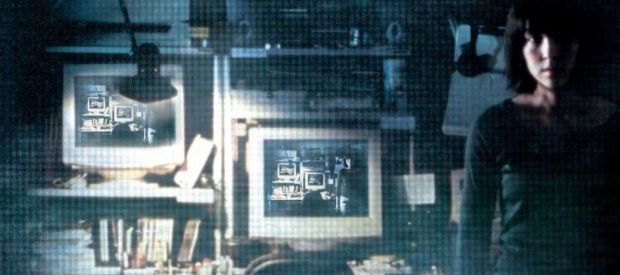

6. Pulse (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2001)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa is a filmmaker in his own class; known for making dark, moody, and slow-burning mystery-horror films, his works centrally feature touches of the supernatural. Quite Japanese in his style, perhaps his most highly-regarded film is Pulse, or Kairo in Japanese (loosely translated as passageway or curcuit).

During the advent of internet communication and webcam usage that took place in Japan at the beginning of the millennium, a young woman named Michi arrives at her missing friend’s home, worried about his well-being. Once inside, she finds him alive and responsive; mid-conversation, she goes into the room he was presently in only to find him dead, having hung himself with computer cables.

As the film continues on, Michi is witness to more people committing suicide (a chillingly realistic jump from a water silo in particular), while simultaneously her and her friends notice strange red-taped doors popping up throughout the city. Meanwhile, across town, a college student named Kawashima decides to begin using the internet. During what appears to be his first online session, he stumbles upon a website which asks him a simple question: “Would you like to meet a ghost?”

From there, the film takes off and begins a downward spiral into the darkness of isolation and despair; as the dead begin to infiltrate and permeate the world of the living, people begin to go missing and Tokyo, one of the most crowded cities in the world, begins to look abandoned and in disrepair.

A rather long film, it has notoriously tried many people’s patience with its slow moving plot and intentionally-minimal action; however, those who give the film a chance will be rewarded with a complex and intricately-developed film. Being a supernatural horror film, there are several sequences that pack the right kind of punch and come just at the right time to keep the viewer engrossed.

That said, much of the horror in this film is of the existential variety: as the main characters slowly start to notice that virtually everyone around them is disappearing, they begin to seriously try to understand why it’s happening while at the same time trying to hold themselves together in the face of a near-apocalypse.

Perhaps originally intended as a study into the effects of technology, and how the leaps in virtual communication have only isolated us further from each other, fifteen years since its release it serves as a much more prescient film considering the current circumstances of Japan as a nation and people.

Under the guise of a horror film about the evils of technology, Kurosawa was able to craft a potent critique of the state of Japanese society and the pitfalls of its own cultural trappings. A shockingly aware film that still stands tall above the other horror films that were coming out of Japan at the time, Pulse is a unique and sensitive film that many have re-watched in their own personal efforts to understand why the events of the film take place.

7. Fando y Lis (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1968)

Although he is known primarily for El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), both iconic works of the 1970s, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s first film has been largely overlooked due to the impact his two most successful films have had. Inherently experimental and jarring as a result, Fando y Lis is a surrealist fever dream in stark black and white.

Set against a barren, desolate badlands many have theorized to be post-apocalyptic, the film centers around its two title protagonists; Fando, a troubled young man seemingly on a quest for truth, and his girlfriend Lis, a paraplegic young woman whom he carts around or otherwise carries by wrapping her around his waist. As a child, an older man told Fando the story of Tar, a mythical city where dreams come true and wishes are granted.

As a young man, Fando and Lis set out in search of the location of Tar in an effort to cure Lis of her paralyzation, and to live in a self-curated paradise. However, along the way their journey is interrupted by a series of encounters with strange, morally-dubious groups of people who may represent manifestations of an internal battle being waged within Fando.

Highly symbolic and often uncomfortable to watch, perhaps the reason why this film has been mostly lost to the annals of time is because of its harsh reception upon its initial release. Conceived and shot entirely in Mexico with a Mexican cast, its premier at the 1968 Acapulco Film Festival was met with a violent riot in reaction to the film’s avant-garde and admittedly disturbing content.

Eventually banned in Mexico, the film was cast into obscurity because the socio-political climate was obviously ill-suited toward experimental or “deviant” art.

On a more realistic level, maybe another reason why the film has seen such an obscure fate is because it’s simply a tough one to watch; the imagery is graphic and brutally strange, rife with psychosexual underpinnings. The soundtrack is a mix of music and incongruent, grating sound effects that seemingly only serve the purpose of furthering a sense of unease in the viewer.

Definitely inaccessible for most people who will not revel in its radical expression, Fando y Lis is nonetheless a shocking firecracker of a film that is worth seeing just for the experience alone.

A curious investigation into the nature of religion, mysticism, death and the possibility of the afterlife, fans of the film have spent decades trying to piece together a cohesive meaning. Like most cinema of this variety, there are varying interpretations which exist depending on who you ask.

8. Masque of the Red Death (Roger Corman, 1964)

In the 1960s, Roger Corman of American International Pictures set out to execute his dream project: a series of full-length gothic horror films based on Edgar Allen Poe’s short stories, featuring Vincent Price in lead roles. Eight films in total were made (though Price didn’t appear in one, The Premature Burial); despite AIP having a reputation for shoddy, low-budget B-films, under Corman’s direction these films were realized as moody and effective horror films.

Masque of the Red Death is often cited as a high watermark for the cycle of Poe films, and it’s completely warranted: with its mix of original material and elements borrowed from a mish-mash of different Poe stories, Corman crafted a surprisingly brilliant and beautiful film that still manages to be deeply unsettling and even frightening today.

Set in the mountains of Italy during the Middle Ages, the film revolves around Prince Prospero, played by Vincent Price. Receiving word that the “Red Death”, a Bubonic Plague-like illness, has reached the mountain territories around his castle, he decides to invite fellow aristocracy to take shelter with him inside while the Red Death decimates the outside world. He’s also a practicing Satanist, a key plot element that much of the action in the story is derived from.

The film is lush with bright colors and a fair share of odd, interpretive dance sequences; the Red Death itself (represented by a faceless hooded figure in striking blood red) is used effectively to juxtapose against different backgrounds, lending the film a visual aesthetic that is hugely impressive and immersive.

The film is also shockingly intelligent considering the low-budget affair that it was intended to be: characters speak at length on their perspectives regarding religion, morality, humanity, and of course, death and what awaits after. Vincent Price, a well-regarded and celebrated actor in his own right, gives what is perhaps his finest performance.

Although known primarily as a character actor who found a niche in the horror genre, his work in this film takes on an almost-Shakespearean quality and elevates the film to a higher level. At once visually-striking and unsettling, Masque of the Red Death is a must-see. (Another film in the series, Pit and the Pendulum, was knocked off this list in favor of Masque- although that film is similarly visceral and intense.)

9. Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

Suspiria is widely-regarded as a classic of the horror genre, however in some ways even that description misses the mark. One of the last films to be printed using the Technicolor process, it’s well-known for its usage of dramatically vivid colors- red, blue, and a demonic shade of green in particular- however even outside of these limited terms, the film is a visual marvel and psychological whirlwind.

The plot is simple: a young American woman named Suzy moves to a famous ballet school in Germany to continue studying her craft, but soon bizarre antics abound, bodies pile up, and she eventually deduces that the school is actually a front for an ancient coven of witches.

The moment Suzy encounters the school itself, it’s as if reality warps and nothing seems to be real; neither to her, nor to the viewer. Faced with strange event after strange event, Suzy’s role as the main character plays out less like a protagonist and more like a naive child wandering through an uneasy dreamscape, one that happens to be filled with death and decay. The interior design of the sets- the wallpapers, the lights themselves, the decor- further accentuate the unreal atmosphere.

Even the acting, which is arguably laughable by today’s standards, seems so odd and off-key that it actually helps the film overall. The death scenes in particular are famous for their grizzly intensity, and the opening death scene has been consistently ranked on “best of” lists. While touted as one of the best horror films of the 20th century, it is much more than that: a surreal visage and savagely beautiful work of art that remains with the viewer long after it’s done.

10. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (David Lynch, 1992)

Made as a pseudo-ending in the wake of the cancellation of the eponymous TV series, David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a uniquely shattering experience. Perhaps unexpected in a list like this one, it has a sticky place in the canon of its parent series: upon its release, critics and fans alike shared a seething hatred for it that has mostly endured in the collective memory.

That said, like other films on this list its reputation as a masterful psychological horror film has grown in the twenty-four years since its release, and its continuing re-evaluation has lead to recent critical appraisal. Although there are elements present that qualify the film as a sequel, it actually functions more as a prequel; the plot follows deeply troubled teenager Laura Palmer during the last week of her life and depicts many of the events that eventually lead to her murder.

For those who haven’t seen the series, the pilot episode opens with her body being found washed up on a river bed, and the event acts as a catalyst for virtually everything that comes after it.

A big part of why almost everyone was disappointed by the film when it was released is because it is decidedly not the TV series; which was a mix of mystery elements, quirky humor, and melodrama that created a refreshing narrative. In turn, the Twin Peaks film is very much a David Lynch film, and as such Lynch’s trademark dark surrealism is on full display, and gorgeously rendered at that.

Lighting is key to much of his work, and this film is no exception: often subdued and sometimes overwhelmingly bright, there’s a masterful use of lighting techniques and the derived color palette. Lynch logic is in full effect, too: dream sequences interrupt waking life without much indication of any shift in perspective; Laura awakens inside of a painting on her wall; people from said painting make appearances in the outside world, and David Bowie makes a bewildering cameo as an FBI agent.

It’s a thoroughly cryptic and uncomfortable experience of a film, but it is also a moving account of a teenage girl’s rapid descent into madness. Laura, the root of the series who only appeared in flashbacks and dream sequences, is given a well-deserved story. She’s a drug-addicted, sex-hungry teenage girl whose own actions may very well have led her to her own demise.

Although it’s made clear from the beginning that the course of the story will inevitably lead to a tragic ending, Laura’s journey of self-destruction is captivating as she unearths harrowing secrets about herself and her family. Credit must be given to Sheryl Lee, who portrays the main character with an incredible conviction and heart-wrenching fragility. She carries the entire film on her back and without her performance at the center, the film would not hold up as its own entity.

Admittedly, while the film makes very little sense to the casual viewer who is not familiar with the series, even viewers who are familiar will have more questions than answers. It makes for a remarkably confusing, but altogether enthralling viewing. Make no bones about it though: it’s fascinating to watch, but it is indeed truly bleak and quite hopeless.

Like the rest of Lynch’s work, it feels a bit like a complicated puzzle that can be analyzed and picked apart through repeated viewings. It’s a damn effective horror film too, which is something that seems to have been lost in the hodgepodge of negative reception that it has been marked and remembered by.

Incidentally, it has much in common thematically with another film mentioned previously in this list, Tideland. Both films center upon young girls who, faced with extreme and untenable circumstances, try their best to escape from their respective situations.

In Tideland, the main character retreats into her own mind, while in Fire Walk With Me Laura Palmer relies on drugs and sex to provide release. But whereas in Tideland the heroine of the film sees an unsure life ahead, in this film the heroine finds death and an uncertain afterlife.

Author Bio: KVNC is a writer, poet, and sometimes-photographer from California. As a young teenager, he discovered a passion for film; starting with Japanese Cinema, and eventually branching out to the rest of the world. He is currently based in Tokyo.