Of the major film movements that have been conceived so far, Third Cinema is currently one of the most generally overlooked. Its body of work isn’t as well known or as thoroughly dissected in film school classrooms as say French New Wave or German Expressionism, but historically and aesthetically speaking, it should be considered just as much.

Nevertheless, one fairly open but reasonable explanation for such oversight can very well be traced to weakening didactic policies concerning international affairs in secondary schools.

Another more direct explanation (that is actually related to the first one) can be attributed to the ingredients comprising this movement’s whole concoction -like the fact that these were truly hard films to make and had to operate based on ultra limited budgets and tactics, or that they tackled head on the status quo in countries ran by repressive governments or that their works came peppered with rabid sociopolitical agendas- since clearly all of these elements suggest a narrow vision that feeds off certain historical models indispensable for a basic understanding of what was then being proposed.

Even by today’s standards, in which almost everything seems to be just a click away, these films remain somewhat illusive for countries other than the ones being represented. Yet, despite having the deck stacked against them, Third Cinema’s pictures, collaborators and spectators, whom faced such consequences as persecution, censorship, exile and death; managed to leave their mark.

The term Third Cinema, which was first billed by Argentinean filmmakers Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas in their manifesto Towards a Third Cinema; made reference to the territorial classification design used during the Cold War.

Solanas and Getino applied that same notion to their project and decided to label a first cinema (meant for lucrative purposes) and a second cinema (the auteur take on creative endeavors), both of which they opposed. Their conception of Third Cinema was meant to be a militant reaction against any form of authoritarian oppression, particularly concerning neocolonialism.

The idea consisted on producing propaganda type content which these filmmakers believed would best benefit and could ultimately lead to a shake up of the masses so as to force their concrete involvement in issues with huge repercussions.

By representing or capturing the crudeness of social structures and power with the firm purpose of challenging those conventions, their cameras turned into weapons and the finished products became instruments intended to protect, liberate and stimulate the poor and marginalized. For them, instilling action on the spectator’s conscience was the key needed in order to establish a new form of mass communication; passive acceptance was no longer an option.

Along the way Third Cinema would encompass films and movements with shared conditions, similar ideologies, worries and aims originating from Latin America, Africa and some regions of Asia. Even though they failed at becoming a unified revolution, the movement still managed to achieve large-scale influential status that reverberates to this day. Their concept has evolved into contemporary transnational film production.

Today Third Cinema’s catalogue serves primarily as an invaluable educational resource that covers many areas from social sciences to art appreciation. The movies on this list have been chosen based on criteria that mix their overall quality, impact and historical relevance to their respective countries.

10. Sugar Cane Alley (Euzhan Palcy, 1984)

When it comes to staging, Euzhan Palcy’s debut feature is definitely on the lighter side of things. Its themes, on the other hand, are anything but. Based on a semi autobiographical novel by Joseph Zobel, this film contemplates colonialism from an existentialist and minimalist frame that sometimes appears to be pretty direct and other times depends more on a suggestive tone.

Sugar Cane Alley is a beautifully shot coming of age story set in 1930’s Martinique that is quite conscious of its privileged natural spaces. With an undemanding structure and storytelling execution, it manages to focus on universal appeal but never at the cost of its own truth. A vivid, compassionate and emotional trip down the pathways of self awareness.

9. Barren Lives (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1963)

One of the most recognized entries from Brazil’s Cinema Novo is the adaptation of Graciliano Ramos’ novel by Nelson Pereira dos Santos. The story is quite simple: a dispossessed family looks for a fresh start and the chance to better themselves in an unknown region against the backdrop of a harsh drought. Needless to say, hopes and reality clash as they always do.

With a composed pacing, heavy Italian Neorealist influence and terrific use of natural light that transmits a character like presence, Barren Lives steps on familiar grounds with a distinctive touch. Forget the samba, the vibrant colors and the voluptuous figures commonly associated with Brazil, this is raw fiction stripped to the bone.

8. Blood of the Condor (Jorge Sanjinés, 1969)

A work that can best be described as both wildly incendiary and gorgeous eye candy at the same time, Blood of the Condor is a love letter from Jorge Sanjinés to the Quechua way of life in Bolivia. The movie proposes a call to arms through a simplistic cautionary tale of two brothers that seems almost taken from a fable, but it’s presented in a more intricate narrative structure that ironically borrows from European avant-garde films.

The latter being a creative decision that Sanjinés soon after admitted to regret. Much has been said about its scathing anti imperialism statement and how it is believed to have played a part in the 1971 expulsion of the Peace Corps from Bolivia. But, above any and all political discourse, the core value of this piece lies within the long sequences where the camera goes into pure observational mode allowing these villagers to just be.

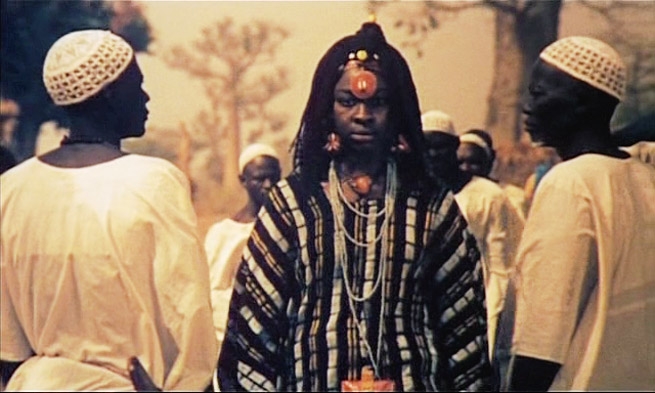

7. Ceddo (Ousmane Sembene, 1977)

At first glance, subordination through dogmatization seems to be the main issue in Ousmane Sembene’s fifth feature-length film. That idea sort of holds together and, to some extent, appears to dictate the pace throughout most of the movie; until the end comes.

To scrutinize this work in such a common manner would essentially mean to deprive it of its own might. And, that might is found in the deep layers of historical courses of action it references and seeps into.

At times Ceddo can seem disorienting in its creative strides and audiences that value modern paraphernalia in filmmaking will most likely find it discouraging after a while, but this is only a testament to how well Sembene combines cultural and aesthetic ideas. But for the sake of a tangible depiction: a Senegalese period piece with no specific date, full of gorgeous visuals and set up in a plain manner so as to contain the high dose of complex topics that abound.

6. Entranced Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1967)

Politics become politricks fairly easily in the fictitious microcosm called Eldorado that Glauber Rocha brings to life in Entranced Earth. This film has art house written all over it: characters directly addressing the audience, the cameras exploit every option of space that they can, dolly shots and close ups come and go as they please, all the while grandiloquent rants and a selection of overdramatic songs command the rhythm of it all.

Though it intentionally relies a great deal on ardent symbolism (literally from the first frame up to the last one) which can be exhausting, Rocha manages to capture the spectator’s full attention regardless of whether that implies love or hate toward his picture.

The style here is so flashy that it doesn’t quite give out a low budget vibe, but the truth concerning its conception couldn’t be more different. The implementation of guerrilla filmmaking was compulsory because of the military junta that ran the country at the time. Subtlety went out the window.