6. Jurassic Park (Spielberg, 1993)

Michael Crichton’s novel, Jurassic Park, is considered his best effort, garnering both social and critical acclaim. Interestingly enough, it started as an idea for a screenplay. Once Spielberg got ahold of the rights, Universal paid Crichton $500,000 to adapt his own novel (which he did).

The film benefited both from Crichton’s own vision in the screenplay and the amazing special effects that were employed to bring the film to life. Never before had viewers scene dinosaurs in the way they were presented in Jurassic Park. Spielberg and Crichton worked well together, and the film benefited from this.

With the incredible visuals and Crichton’s true-to-form modern Frankenstein narrative in play, the film had far more going for it than the novel.

7. The Shining (Kubrick, 1980)

Stephen King has famously exclaimed his hatred of this adaptation, questioning Shelley Duvall’s portrayal of Wendy, the very abrupt changes to the novel, and the changed ending.

King’s novel was much more about Jack’s struggle with alcoholism and his inner demons than actual ghosts and possession. King explored the familial struggle and the implication of alcohol (stemming likely from his own experiences with addiction), and he criticized Kubrick’s film for making Jack appear already crazy when he goes in for his job interview.

It’s perhaps a legitimate grievance, but Kubrick’s adaptation is wholly chilling and unnerving in a way King’s novel wasn’t (and never attempted to be). Kubrick wasn’t exactly known for making horror films, and there could be an argument that this isn’t necessarily a “horror” film in the strict sense of the term. But Kubrick created an entirely different monster with this film, not only by letting it stand on its own, but also by boldly changing critical plot points from the novel.

8. The Silence of the Lambs (Demme, 1991)

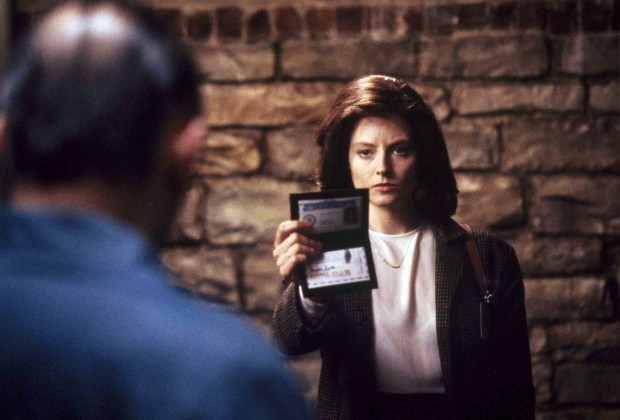

If anything, Demme’s adaptation of The Silence of the Lambs is proof that faithful adaptations can be just as successful as adaptations that play with the source material. There are a few changes from Harris’s unnerving novel, but – for the most part – Demme’s adaptation is true to its source material.

Its success comes in casting. Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins not only were perfect choices for their respective roles, but they also brought an entirely different side to their characters. In the novel, there is no doubt that Hannibal Lector is to be feared, but Hopkins’s performance was disturbing and riveting on an entirely differently level. Hannibal Lector went from an abstract idea in our minds to a person with a face on the screen.

In this case, the book and the film are likely equal since they both successfully set out what they hoped to do, but the film adaptation really creates a different sense of dread than its literary counterpart.

9. Gone Girl (Fincher, 2014)

David Fincher’s powerful film, similar to Demme’s adaptation of Harris’s novel, stayed true to the film (though Gillian Flynch, who wrote both the novel and the screenplay, said that she slightly changed the ending of the film, though not to an amount where it was incredibly noticeable).

The difference between these two incarnations of the same story really has to do with Fincher’s incredible visuals and the soundscape of the film. In a novel, the image is what you discern in your mind. It’s the images you, as a reader, create from the details of the novel.

Film doesn’t have to worry about that, and it adds a further level: it allows you to hear things without you having to internally replicate those noises. A scream is no longer trapped in your mind, it’s bounced around a room and thrown at you.

And Fincher really delivers on these two fronts, changing the entire feeling of the story both subtly and overtly. It’s one thing to create dread with prose and dialogue, it’s another to assault the senses and create an experience that oozes tension. And that’s what David Fincher’s Gone Girl does.

10. No Country For Old Men (Coen brothers, 2007)

The Coen brother’s film adaptation is another excellent example of how being faithful to the source material can prove to be just as important as being unique. The real shining difference between film and literature are their respective literary methods.

A film will always be different than a book because we watch movies and read books (a rather simple observation) and therefore filmmakers are already creating unique works by translating a book to the screen. The directors, like Kubrick, who go above and beyond are few and far between, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Like many other films on this list, the film adaptation really benefits from its casting, cinematography, and direction. This is to say that, by being a film (and being outstanding in those regards) it is a successful adaptation. But the real game changer is Javier Bardem, whose performance as Anton Chigurh brings a palpable menace, and a face, to the character a reader could only imagine beforehand.

In this way, the film – by being so faithful to the source material and by perfectly executing the facets of filmmaking necessary – rivals the source material because it takes the power of McCarthy’s novel, brings it to the screen, and makes it accessible to millions of people in a way the book could not do.

Author Bio: Keith LaFountaine is a senior at Lyndon State College, planning to graduate in May. He is majoring in Cinema Production, and is currently working on his senior thesis film: “Departure.” Keith hopes to eventually direct narrative films.