5. Cat Soup (Tatsuo Sato, 2001)

At only thirty-four minutes, Cat Soup is a short and deeply weird tale of a very different take on the afterlife. In this tale, the realm beyond our own is called ‘Other Side’ and that’s where we find the protagonist, Nyatta, as he searches to retrieve his sister Nyako’s soul. Of course this being a surrealistic tale, these siblings are anthropomorphised cats.

Nyako has been rendered brain-dead and her brother must venture into this dark world in order to bring her back to normalcy. This of course is very much open to a lot of interpretation as Cat Soup is one of the strangest tales, animated or otherwise, to be put on screen.

Characters are drawn as both cute and familiar, and set against detailed backdrops and landscapes. These themselves are what give this tale it’s darker edge. It’s like mixing Hello Kitty with Hieronymus Bosch. Director sato has drawn from a lot of medieval and biblical imagery to bring this version of a maybe-hell to life.

And soon, some these more innocent-looking characters are subjected to some brutal and grisly sequences. It’s this contrast between such lovable looking creatures, and our main pair are quite pure and virtuous, against such a nightmarish environment that gives the story such a fever-like presence.

4. Redline (Takeshi Koike, 2009)

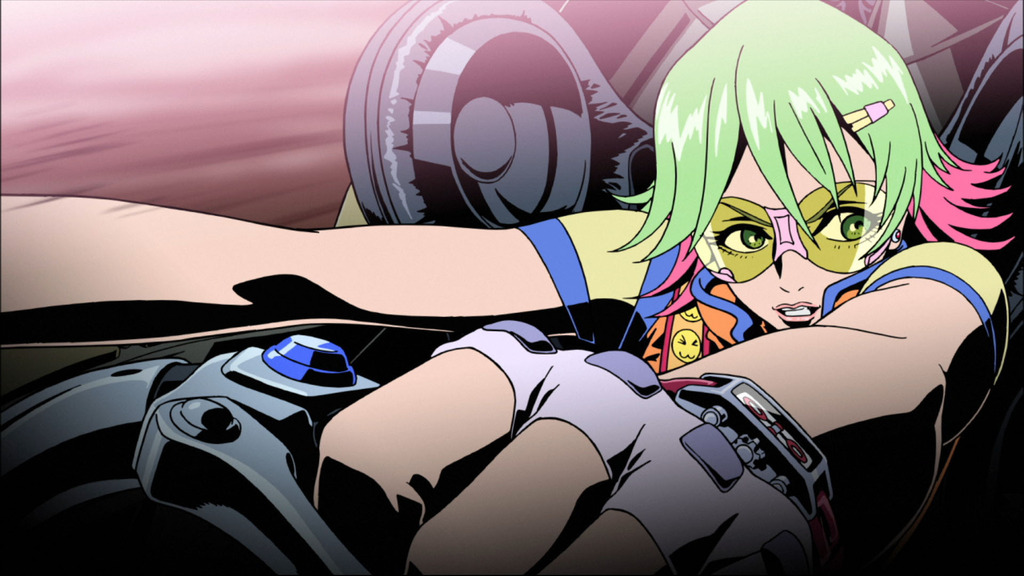

A delayed and troubled production that finally saw the light of day years after originally planned, Redline is the result of over one-hundred thousand hand made drawings and a collective of animators and artists seeking to push action storytelling into new grounds.

The story follows JP, a rare human able to compete in the heralded Redline races. In a world filled with canine-humanoids, cyborgs and aliens, JP meets fellow human and racer, Sonoshee, must decide if winning the race is the most important thing to him. The character and vehicle designs are blistering with originality.

From the dog-men who dominate his world to the wide array of cars racing, there is an evident love to both action and sci-fi. And the fact that this was all cel animation, every frame drawn by hand, puts many mixed media animated titles and CGI slugfests to shame.

Inventive use of light and colour really draw the viewer into the high-velocity race scenes. Line and movement is also to ramp up the speed in which the racers travel. Characters and vehicles bend and contort from the norm, dust and debris fly across the screen in a hail of motorized mayhem.

3. Mononoke (Kenji Nakamura, 2007)

A twelve episode series set in the Edo period of Japan, ‘Mononoke’ follows a lone wanderer known as the ‘Medicine Seller’. Each episodes finds him encountering a different, unworldly spirit, or mononoke. He must learn the truth (makoto) reasoning (kotowari) and it’s true shape (katachi) before he can dispense of the spirit with his samurai blade and move on to find another.

The twelve episodes are divided into five ‘arcs’ and each one contains it’s own distinct style. The first arc uses a rustic, earthy, naturalistic palette. The second is a psychedelic rendering of feudal japan; bright pinks, oranges and blues.

The final arc is more modern, sharp and bold shapes and colours. As a whole, this anime uses such a classically Japanese style, as if it was originally animated centuries ago. It looks as though it was all constructed on course, ancient paper but that’s not the case, a pure stylistic choice that emphasis the historical influences and themes.

Much computer effects are evident, a dizzying display of layered form and movement. All throughout the editing is often precise and controlled, other times shots zip in-and-out of each other with a fury rarely seen in animation.

A stylistic experiment that works both as a visual innovation and an enthralling story, Mononoke received critical praise for combining and truly harmonizing style and substance.

2. Genius Party (Various Directors, 2007)

An anthology film with seven different shorts all by different directors, Genius Party is seven different exercises in animated experimentation all rolled into one. From the music video-esque, hand crafted opening, also titled ‘Genius Party’, the surreal and nightmarish ‘Deathtic 4’ to the cybernetic, cold and sterile ‘Limit Cycle’ to the more traditional, and melancholy ‘Baby Blue’, this feature covers a wide variety of techniques and narrative devices.

‘Happy Machine’ uses a basic, childlike style to help show the world through the newborn protagonist’s eyes. Shapes and colours are skewed, and live action footage is composited into animated frames to emphasis the surreality of this infant’s new world. ‘Shanghai Dragon’ also uses a simpler, innocent style but contrasts with far more detailed mechanical and weaponry.

It’s a tale that ends in a flurry of wondrous action cutting and shot selection, it’s joyfully juvenile. ‘Doorbell’ utilizes manga styled fine lines and limited, washed out palettes to tell the macabre tale of a man and his doppelganger. All told, there’s something for every anime enthusiast in ‘Genius Party’ and just about every technique in the book is utilized.

1. Tekkon Kinkreet (Michael Arais, 2006)

American animator and visual effects artist Michael Arias is the only non-Japanese on this list, yet for his first feature, he made his characters look more distinctly Japanese than his native counterparts. The story tells of two friends, the streetwise and cynical Black and his naive and more purely moral White, and their efforts to help save their home, Treasure Town, from a criminal organization.

While the characters are relatively primitive in their rendering, retain a basic realism beyond the wide-eyed, cartoonish characters presented in anime. Treasure Town is an immensely detailed landscape.

A mixture of european, brazilian and asian architecture that is rich with depth, colour with a lived-in, fantastic authenticity. The camera moves through this world with a combination of traditional tracks and pans, but Arais also uses 3D assisted movements to create a more immersive feel where spatial coherence is expertly utilized.

It’s a very adult story, one where the hopes and desires of the young are constantly set against the realities of a world run by the old. Fantasy and reality blend into one as two children seek to take control of an increasingly chaotic world.

Author Bio: Jaren Park is a writer and director from Perth, Western Australia. A graduate of C.I.T’s Screen and Media program, he is writing both a feature film and developing a sci-fi web series. He is also a prominent extra, rarely seen but appearing in numerous shorts and commercials.