Back in 1978, a former advertising executive unleashed upon the world a hefty text on the imminent perils implicit in the act of watching television, channeling the as-of-yet accurate prophecies foretold in the previous decade’s examination of man’s many newfound extensions.

Jerry Mander’s Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television echoes the theory debuted in Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media that “the medium is the message” so as to judge this particular medium not on its programming, but on its own objective technology, notably substituting uncompromising urgency for the ironic and often opaque metaphors offered in McLuhan’s handbook for anticipating the 21st century.

Mander’s apocalyptic vision of being alive in a time since television has happened to the world and cannot ever unhappen sets it apart from its portentous predecessor as it annihilates any possibility of positivity in the future of visual technology.

More recent works postdating any credible research on the effects of screen activity on the human brain such as Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad is Good for You (which defends pop culture’s increasing complexity, completely misses the point of McLuhan) and Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows (which applies medium-as-message theory to the internet, isn’t totally pessimistic) counteract much of the dystopian postulations put forth by Mander, who mostly cites Brave New World and 1984 as sources. But Mander’s book is just as much a series of arguments defending the forgotten resource of personal observation in a science-obsessed culture.

Mander maintains enough composure in his writing to organize his rebuttal against the ongoing event of an utterly unavoidable medium into four arguments, which form an analytical backbone for the exponentially-germinating colossus that is modern screen technology.

Regardless of whether the contents of NBC’s new fall lineup have progressed intellectually or further succumbed to the superficial pleasures that constitute the abstract spiritual force known as “good television” – and taking into consideration the fact that TV has begun to invade our free time outside our living rooms thanks to streaming content and truly unforeseeable advancements in telephonic technology – the core philosophy of television, as outlined by the man whose birthname is remarkably synonymous with the very term for one of television’s many manipulative powers, remains the same,

In accordance with the incessant referencing of lit-savvy McLuhan and the observational analyses of social, psychological, and political manipulation put forth by Gerry, er, Jerry Mander, this list offers wholly unscientific evidence in support of Mander’s claims in the form of ten real-life examples of instances in which screenwriters (with varying degrees of awareness) were inspired to illustrate the mind-altering intrusion of television’s soft glow on their hapless personas.

INTRODUCTION

1. War to Control the Unity Machine (Network, dir. Sidney Lumet, 1976)

The two unspoken tenets of television which have traditionally set the medium apart from movies, music, and literature are the established corporate powers that mediate all of television’s content to everyone with access to network programming, and the necessity for all of television’s content to be presented in a way that is optimally engaging and, thus, lucrative.

Where the oppressed voices of minorities and unfamiliar cultures, as well as intellectuals, the impoverished, and temperamental loons, are limited to mediums achievable by anyone with a writing utensil or recording equipment, the broad reach of network television possesses the distinguishable asset of conditioning an entire nation to the ideologies of those holding the reins.

Network responds to these assertions with two corresponding hypotheticals: what happens when an established network figure turns against these controlling powers, and what happens when this revolt makes for “good television”? As the result of his imminent severance from his network due to poor ratings, newscaster Howard Beale unwittingly finds himself with a growing amount of freedom on air after ditching his script during a newscast to announce his imminent suicide.

Consequently, he utilizes his allotted air time for a public apology to shed light on the “bullshit” of his profession, earning him the national spotlight, his own program to vent his frustrations to all of America, and, of course, a nationally-renowned catch phrase.

As evinced by recent American political developments, spewing the right sentiments at the right moment to a nationwide audience familiar with your name for reasons totally unrelated to your celebrity can generate a unified upheaval in a country’s social fabric and collect an attentive audience eagerly anticipating their tele-vizier’s every word, gladly substituting outsourced ideology for personal philosophy.

Network’s relevance lies in the direct correlation between Beale’s gradual mental breakdown (or clarity) and his positive critical reception, which parallels the increasingly taboo stunts undergone by real-life public figures to gain access to airtime. “Freedom of the press is limited to those who own one,” wrote journalist A.J. Liebling, and in a time of viral videos and a tightly-knit global village, television remains the foremost widely-available medium which maintains the press’s exclusivity.

ARGUMENT ONE: THE MEDIATION OF EXPERIENCE

2. The Walling of Awareness (Safe, dir. Todd Haynes, 1995)

While humans have been living in man-made environments for millennia, these manufactured spaces have only recently become mediated by panoramic capitalistic insignia overdosing American culture with edenic projections of wealth and comfort with an incomprehensible focus on selling a pre-packaged way of life over individual products.

The effect is what Don DeLillo’s scientists grandiosely referred to as the Airborne Toxic Event, or what a controversial minority of actual scientists call Multiple Chemical Sensitivity

Safe acts as a domestic microcosm of the effects a subliminally toxic environment have on their target demographic, depicting the intensifying nausea incited by Pottery Barn catalogues and a peer group of Joneses for which it’s socially imperative to keep up with.

We see the film’s reserved subject – upper class housewife Carol White – at her most petulant following the delivery of a new set of couches to her living room in the wrong color. The obtrusive black furniture severely contrasts with the pallid color pallet which constitutes the rest of the house’s decor, not to mention Carol’s wardrobe, skin tone, and acquired surname.

Though there’s little reference to television in the film, the medium haunts the sterile domestic scenes via the subtext of its late-1980s setting, the era of DeLillo, Neil Postman, The Running Man, and the first American president to be extracted from the guts of TV.

Safe speaks to the entrapment a mediated environment sets through the commercialization of readymade domestic identities and concurrent modernist sensory deprivation typical of 20th-century-based allergies, both ridiculing those who fall prey to its allure and forecasting total exile to an industrialized desert igloo as the sole remedy.

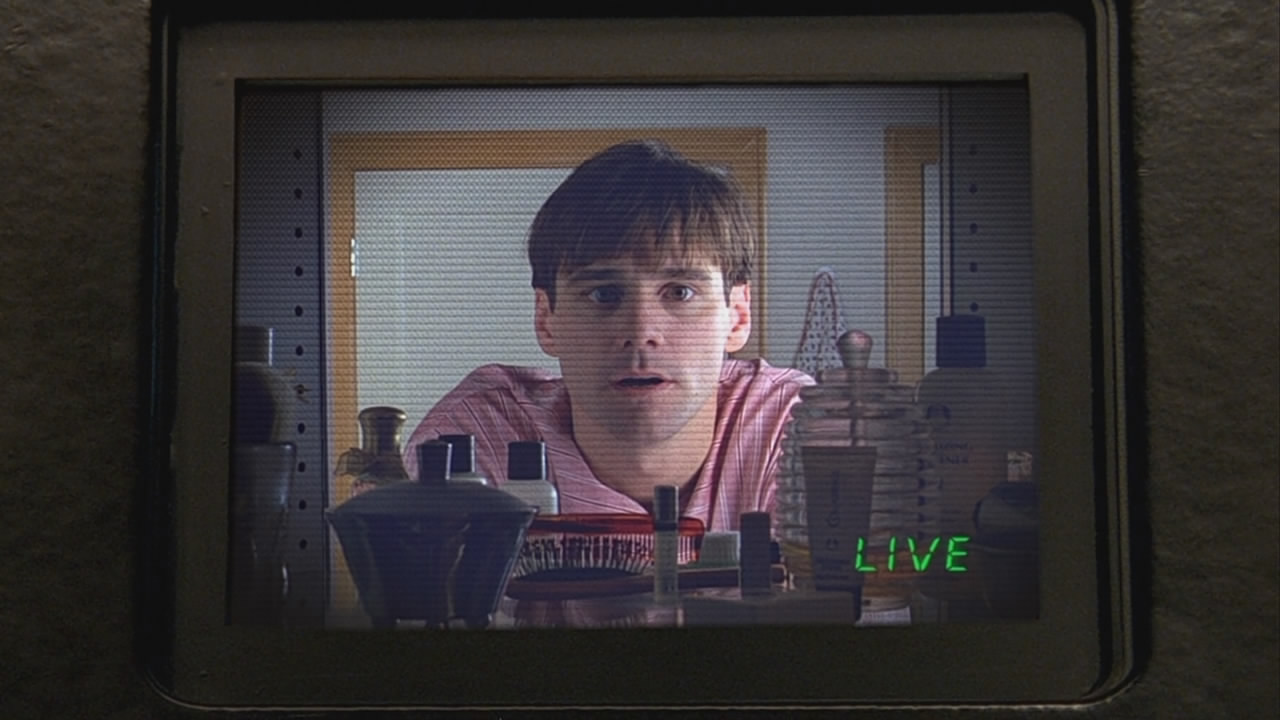

3. Adrift in Mental Space (The Truman Show, dir. Peter Weir, 1997)

Before film, actors were easy to identify by simply observing their appearance on a stage. Similarly, with the advent of film, an audience recognized actors immediately due to their two-dimensional appearance projected on a screen.

Though preceded by the ambiguity of reality in documentaries like Nanook Of The North, television was the mainstream entry point for the distinction of “real people” in the context of screen media. With the recent popularity of reality TV programs devoid of such legally-obligated disclaimers as “not a real doctor” and “dramatic reenactment” it’s become a complex affair dissociating fact from fiction.

Demanding copious answers to the intellectual and ethical role of the viewer, The Truman Show addresses the conflict of desensitization to what we perceive as “real” through the prolonged suffering of the film’s titular show’s titular subject.

As Truman Burbank unknowingly carries out his mundane daily routine under the watchful eyes of the entire world, the reality of his misfortunate existence within the ultimate mediated environment is lost on its viewers who can only view the program’s content as entertainment, his pain as “good TV.”

Much like Mander’s anecdote concerning a woman whose immediate reaction to a blood-soaked body suddenly materializing in front of her car was to recall similar gruesome scenes from television, the fictional viewers of The Truman Show and real viewers of the news will likely enact their oft-used reflexes to televised content in emergency situations and model their delayed reactions on those of television actors. Did anyone shout “someone call 911!” in an emergency rather than doing it themselves before television introduced this dramatic effect?

ARGUMENT TWO: THE COLONIZATION OF EXPERIENCE

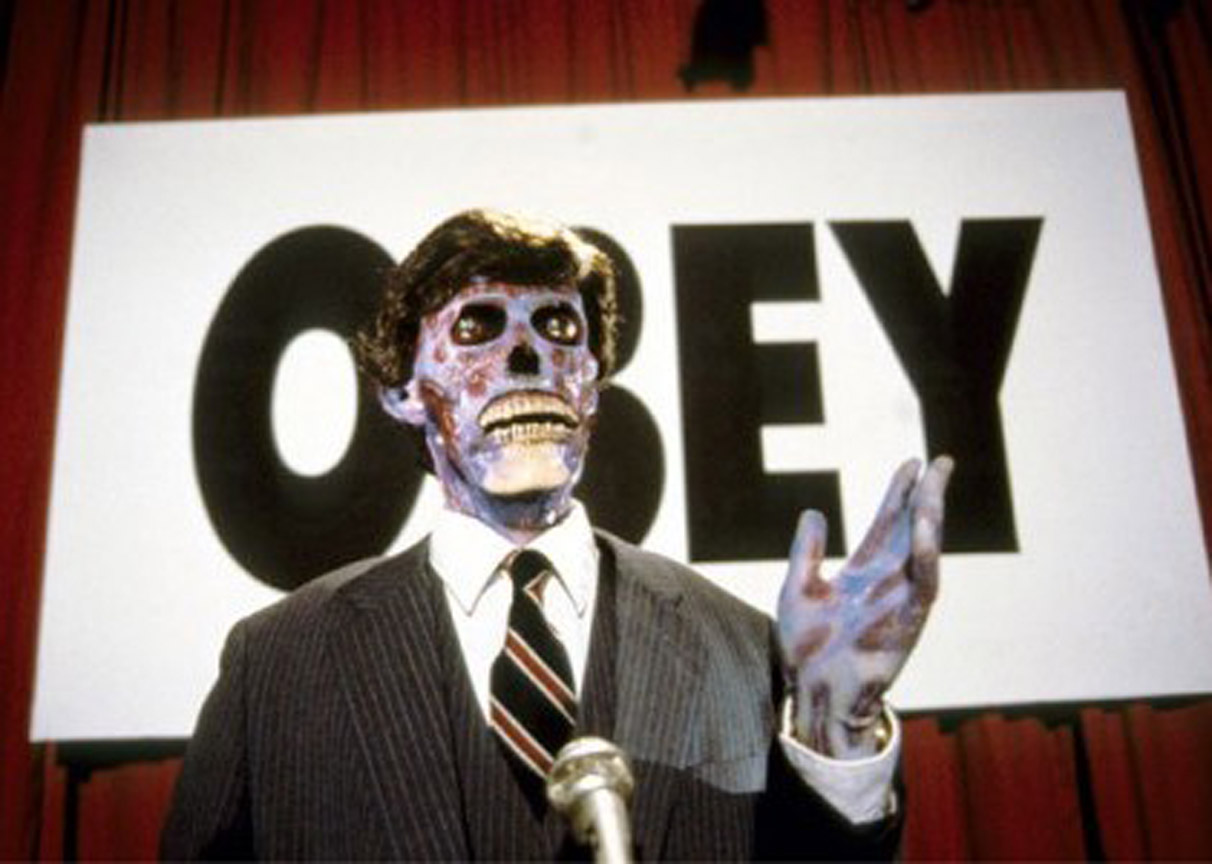

4. Advertising: The Standard-Gauge Railway (They Live, dir. John Carpenter, 1988)

In discussing the ethics of advertising, Mander makes reference to the short-lived European revolutionary group the Situationists, who describe our submission to advertising as “buying ourselves back,” since the voids inflicted upon us by certain products didn’t exist before the items did. Such unnecessary necessities aided in capitalism’s redefining of “value,” for which every square inch of the natural world must be exploited.

By redefining “value,” capitalism has also helped rewire human desire to account for artificial needs, which take the form of, say, a set of couches to match the cheerless modernism of your living room. Such items are made to seem important by the subliminality of their promotion – where “SALE” translates to “CONSUME” and “ACT NOW” means “OBEY” – and are presented as stepping stones in the universal quest to marry, reproduce, and stave off all independent thought.

As They Live observes most famously in its five-and-a-half-minute hand-to-hand combat scene, the perceived insanity of those unable to fit this social arrangement must face the tedium of resistance involved in overthrowing the mindset of passivity sown deep into the individual consumer.

How can one explain the implicit value of an object that eschews financial metrics to someone who refuses to peek into the oddly-fashionable lenses of reality, and complains every time you interrupt his TV signal with your anti-consumerist preaching?

ARGUMENT THREE: EFFECTS OF TELEVISION ON THE HUMAN BEING

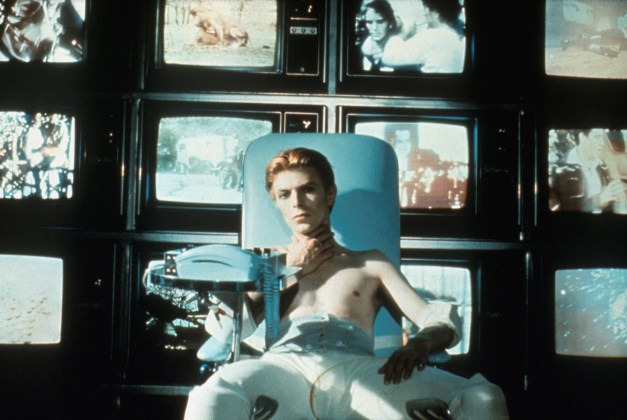

5. Sick, Crazy, Mesmerized (The Man Who Fell To Earth, dir. Nicolas Roeg, 1976)

Terms like “brain-washed” and “zombie-like” are sure to be met with an eyeroll when diagnosing the state of the television viewer as these seemingly exaggerations have solidified into casual cliches most recently assigned to binge-watching on platforms like Netflix and Hulu. But the addictive format of the contemporary cliffhanging thriller and the increasing ease with which TV shows make themselves available can certainly be viewed as a threat to productivity, sometimes detrimentally so.

In the case of The Man Who Fell To Earth, television acts as yet another vice for which visiting extraterrestrial Thomas Jerome Newton becomes too engulfed in to carry out a rescue mission for family and friends on his home planet.

Equating the over-consumption of television with alcoholism emphasizes the medium’s addictive quality while the disconnection with which Thomas engages in the act of viewing (i.e. watching several TVs at once) stresses its inherent mindlessness. “Stop it, get out of my mind, go back from where you came,” he pleads in a fit of apparent schizophrenia.

Regardless of content, the willpower required to divert one’s eyes from a ceaseless barrage of moving images is staggering, and the thought of beginning a relationship with the medium as an adult totally unassimilated with such lazy escapism is almost more unthinkable than the reality of television’s linchpinning of our modern era.