6. The Ingestion of Artificial Light (Poltergeist, dir. Tobe Hooper, 1982)

In Four Arguments, Mander struggles to find definitive scientific evidence for the negative effects of frequently staring into an untested light spectra for an extended period of time, but makes an interesting comparison: the growth of plants is not only affected by the difference between natural outdoor and unnatural indoor lighting, but the type of light and the interference of an intermediate window also heavily impact growth rates.

In terms of television, then, the significantly-less-scientific question arises: how does a human develop differently when she is raised on the artificial light of televised reality in comparison to the natural light of pure human existence?

For five-year-old Carol Ann, poorly-supervised and presumably quite liberal consumption of television transforms her into the film’s eponymous subject: a poltergeist haunting her negligent parents and indifferent siblings by dragging various media-inspired horrors into the family home while her disembodied voice calls for help from an unidentified source.

Where John Carpenter diagnosed the root of domestic fear as an outside force breaking its way into the family unit a decade previously, Poltergeist accounts for the antennaed hellion disrupting the family from within.

What begins as a nocturnal dialogue between the girl and her family TV set evolves into her abduction into a “different sphere of consciousness,” a dimension likely fabricated by the mindless content of late-night television and a deficiency of human contact.

While the whole family falls prey to the screen’s psychological vacuum, Carol Ann’s susceptibility can most likely be attributed to the ever-present concern of television corrupting younger audiences, perhaps even positing addiction to the medium as a new rite of passage for American youths not preoccupied with team sports (and a healthier visual alternative: movies), as her same-aged brother Robbie evidently is.

7. The Replacement of Human Images by Television (Being There, dir. Hal Ashby, 1979)

But what would happen if Carol Ann hadn’t been rescued by her parents as a child, if she remained in her new sphere of consciousness up until middle age, when estate attorneys step in to pry the lifelong victim from her televisual guardian long after her conception of reality could be disassociated with the artificial logic of TV? Among other side effects, Mander suggests an inability to distinguish fiction from fact, a fatal suppression of imagination, and a unified image bank for personal and public memory.

Though Mander would argue that Hal Ashby’s adaptation of Jerzy Kosinski’s novel Being There renders a blow to the imaginative process required to create one’s own images from a written text, its treatment of the subject matter complies with the hypothetical dissonance suffered by a feral being assimilating to a world of non-televised goings-on at an advanced age suggested by Mander.

Chance the Gardener is a caricature of the TV-shaped consciousness stripped of all creative thought within a caricature of an environment wherein unimaginative quips stripped of all context are praised for their ambiguous insight.

It’s a symbiotic relationship: TV’s artificial insemination of the mind and the artificially inseminated mind’s entitlement to TV air time. As the viewer performs his sexuality the only way he knows how – as it’s portrayed in a TV syndication of The Thomas Crown Affair – his interpretation of this reality is filtered into the greater human consciousness, further diluting natural human instinct per the melodramatic images perpetuated by the late 20th century’s own machine in the garden.

ARGUMENT FOUR: THE INHERENT BIASES OF TELEVISION

8. Information Loss (The Model Couple, dir. William Klein, 1977)

Television’s history of excluding or mainstreaming non-dominant cultures is far from the medium’s only bias glossing over crucial information needed to comprehend the full scope of human experience. Much of TV’s bias, though, comes from its exclusion of the sensory cues which subtly work their way into the telling of a story through the medium of film.

Much of television’s dependence on superficial shot/countershot exchanges in focused close-up – and restriction to a thin spectrum of emotional expression – eliminate peripheral information, ambiguity, and subtext in favor of calculated and easily digestible scenarios transparently dictated by the data collected to define “good television.”

Such is the apparent ridicule of William Klein’s satirical depiction of reality television in The Model Couple, a sterilized predecessor to The Truman Show in which the subjects are filmed and broadcasted not by an artistic godhead micromanaging an extensive mediated environment and nitpicking cinematographic details, but by a laboratory full of social scientists.

Not only are the subjects a glaringly normal and uninteresting young French couple, but the way they’re depicted on television is vastly different from the way the film’s audience sees them. The televised panels debating the artistic significance of the couple have nothing but surveillance footage to work with, while Kline (a renowned photographer) uses his camera as a tool of total subjectivity, excluding a dinner party scene comically shot almost entirely in extreme close-up.

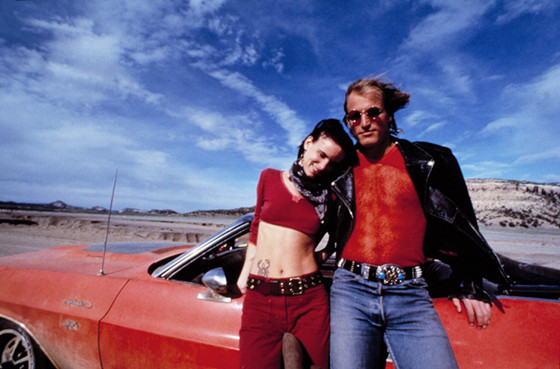

9. Images Disconnected From Sources (Natural Born Killers, dir. Oliver Stone, 1994)

When Walter Benjamin voiced his concern for the death of the ineffable sensory experience linked with an idea’s original context in a work of artistic reproduction – what he calls its “aura” – he probably wasn’t prophesying visual media’s impending undoing into base representations of savage violence irresponsibly removed from any sort of moral dialogue justifying or condemning the acts.

But at a certain point, the media became aware of the fact that images of life were no longer worthy of the public’s attention, and a new bias for death was born, spurring a normalcy of irresponsible hypothetics when speculating upon the context of violence in breaking news stories before all the facts have been made available.

Though many saw Natural Born Killers as the quintessential example of such mindless violence, the movie is a parable concerning the downfall of a culture whose inability to understand media ultimately leads to the faceless beast wreaking havoc on its unsuspecting victims.

With other films like Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole – and more recently Dan Gilroy’s Nightcrawler – in mind, Killers can be seen as a hyperbolized projection of the horrific scenes being relayed by manipulative sources in the minds of a submissive viewer.

The fragmented, assaultive editing legitimizes the story within the mindset of a television viewer receiving the information in bits and pieces interspersed with loud, colorful, and totally irrelevant advertisements, while the laugh track from previously-viewed sitcoms still rings in the viewer’s ears at the least appropriate moments.

10. Artificial Unusualness (Videodrome, dir. David Cronenberg, 1983)

The ultimate ruse of television, Mander concludes, is the viewer’s belief that what they’re seeing is sensational – a jaw-dropping season finale, a barnburner World Series, live coverage of an active shooter – but what they’re really seeing is 32 inches of 1080p resolution framed within an otherwise-unspectacular living room.

The unusualness is artificial, while the deep impressions in the viewer’s couch cushions are all too real. The act of staring at a piece of furniture is mind-numbing, but the temptation of the flashing screen dissolves resolves and convinces the viewer that what they’re seeing is different from what they experienced an hour ago on a different channel.

Were it not for the mystic lure of “good television,” which stems from a promise of what Mander calls an “artificial, impossible, fictitious unusualness” just out of reach, an audience would be entirely displeased with the medium. In Videodrome, Max Renn’s status as president of a UHF TV station is shaken when he observes that no such quality programming is being offered on his network.

While CIVIC-TV being a mostly-pornographic station can simply be written off as Cronenbergian commentary on the dregs of popular culture inhabiting the airwaves, Renn’s introduction to the Videodrome footage suggests that even TV executives are susceptible to being swallowed up by agreeable programming, eventually becoming numb to the same sensational content they’re inflicting the average viewers with.

For Renn, as for the television audience, Videodrome represents the possibility of a mythical reality which originates as a visual stimulus and grows into a cerebral phenomenon coaxed by the artificial promise of the fantastical spectacle’s existence.

As the film ends with Max sacrificing himself for a reality at odds with rationality, the television viewer surrenders their cerebral selfhood for an extreme emotional connection with the plastic Panasonic rectangle vehemently disagreeing with the beige upholstery distinguishing our supposedly individualistic environments.

Author Bio: Mike LeSuer is a Chicago-based writer with a focus on music, media, and film, though he prefers the term “movies.” Little else is known about him.