6. Raging Bull (Dir. Martin Scorsese)

Jake LaMotta is a fighter. A middleweight boxer and a jealous lover – he’s always fighting for something. Jake has an overinflated ego, and a disturbing sense of honour. Raging Bull is about the only Scorsese film that doesn’t romanticise the chauvinistic gangsters of 1950’s New York; Jake LaMotta isn’t a role model, and watching him doesn’t fill you with a sense of admiration or envy – unlike gallant Henry Hill, from Goodfellas.

Raging Bull slowly blurs the line between the ring and Jake’s home life: first taking his own anger and jealously into the ring, then his vicious appetite for violence into his home. Scorsese often parallels the action within the ring to Jake’s violent love life, primarily through the use of sound and silence.

One interesting parallel is drawn between Jake’s first meeting with Vicky (his eventual wife) and his final fight Sugar Ray Robinson. In his first meeting he watches Vicky drive away with her friends – other men – as he stands, helpless, outside the club they were in; the sounds of his location are dulled to almost nothing, and the soundtrack is the only thing that can be heard – until it’s all over, and Vicky is gone with another man.

In the fight with Robinson, Jake can barely stand but is ready to take the final punches Ray can deliver; the sounds of the ring are dulled until Ray finally hits him – he takes the final blows, but he doesn’t fall. In both scenes, Jake is helpless; he knows what will happen and he can’t prevent it. He becomes numb to his impending defeat, and he becomes numb to the sound associated. It’s his only way of coping.

7. Band of Outsiders (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

Band of Outsiders is an intoxicating interplay between romance and criminality. The three lead characters – Odile, Franz and Arthur – plan to rob the house Odile is lodging in.

Like any film of the French New Wave, there is a sense of honesty in Band of Outsiders; it’s so honest about what it is – a film. For example, the voice-over throughout the film is spoken by Godard himself: the director speaks over the film, even explaining parts of it! As for honesty within the narrative, there is an amusing lack of it – which is made all the clearer by the contrasting honesty of Godard’s cinematic style.

“A Minute of Silence” – as I, and others, call it – is possibly the most famous scene in the film. Odile, Franz and Arthur are sitting around a table in a bright Paris café; an almost slapstick routine has just been performed by Franz and Arthur, fighting over the seat next to Odile, and Arthur has just spiked Odile’s drink. They decide to engage in a minute of silence. The audio track of the film is cut completely after Odile’s three second count in, they make it through thirty-seven seconds, then the silence is broken by Franz.

On the surface, this silence may seem like another gimmick of New Wave editing, however, it’s much more than that: this moment of silence is one of the most honest moments of twentieth century cinema. Every film reiterates thematic and emotional elements audio-visually – they’re sad and the frame is blue, they’re angry and the world is noisy, etc. – but this moment makes it clear. They are silent, the film is silent – it’s unmistakable.

8. The Silence (Dir. Ingmar Bergman)

The final film in Ingmar Bergman’s “Trilogy of Faith”, The Silence portrays a world devoid of God, of affection, and of language. Bergman utters true silence, after two films of distant murmurings. If Through a Glass Darkly was a search for God and Winter Light a call for God, then The Silence is the nothingness with which God – present or absent – replies.

A dimly lit carriage rattles along, lullabying two women to sleep; a young boy seems restless. The boy asks what a sign on the side of the carriage says, one of the women replies “I don’t know.” A greater weight is place upon this after we find out that Ester – the women he asked, his aunt – is a translator, yet is unable to interpret the sign.

Directly before this opening scene, the credits roll: white on black, to the sound of a clock hurriedly ticking. Throughout the cinema of Bergman, the ticking of a clock has become a violent reminder of one’s own mortality. The ticking suddenly stops as the film cut from the credits to the face of the boy, Johan.

This cut from Bergman’s morbid leitmotif – the clock – to the youthful face of Johan, in diegetic silence, creates a striking contrast. Bergman juxtaposes several ideas: life against death, a boy of youth against darkness and time; faith against knowledge, unexplained sound against a proven silence; understanding against ignorance, written words against a boy without a fully developed understanding of language.

This single cut presents a throng of interpretations, and each may be equally valid. Silence is pure and unchanging, therefore it can be replicated and become associated with specific themes; however, unlike other audio-visual events, it is natural and requires no justification.

9. A Man Escaped (Dir. Robert Bresson)

Robert Bresson is known for his use of constructivist edit techniques – cutting from close up to close up, slowly building the world around the characters. When this is combined with the inherent openness of pure diegetic sound design, Bresson creates a kind of cinema that focuses you on specific elements – using image – yet allows you to explore further afield – by using acousmatic sound to build a world beyond the frame.

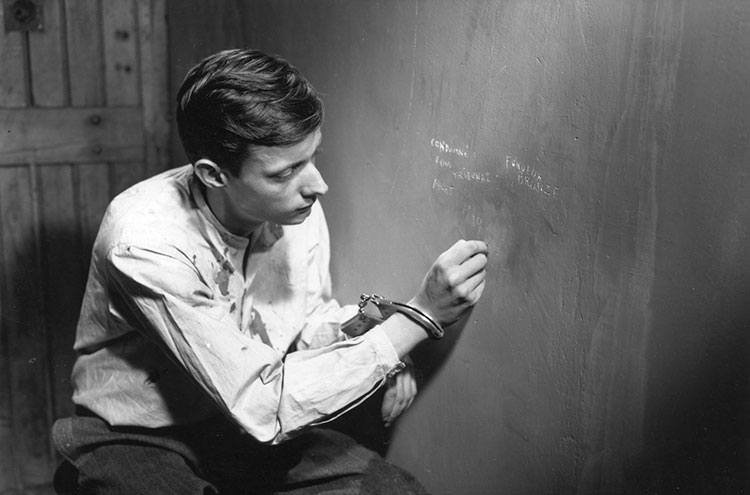

A Man Escaped is the story of Fontaine, a French Resistance fighter, attempting to break out of a prison where he is being held by German officials. He scratches, and sharpens, and chisels; cracks, springs, whispers; then becomes silent, and listens.

Bresson gives the audience the sounds Fontaine can hear, and invites them to listen with him. This draws us into the cinematic world, by requesting something of us – we become involved, therefore we feel closer to the characters. This not only allows us the feel the emotions of the characters, but allows us to project our emotion onto the characters.

So, when silence comes and we are left hearing only the distance murmurs of our world, anything we perceive here gets fed into the narrative: we heard a car out of the street, that could be one of the sounds Fontaine fears so much – the line is blurred. It’s incredibly hard not to see the edge of a screen, but to confuse the sounds of your world and at cinematic world is far easier.

10. Amour (Dir. Michael Haneke)

Michael Haneke’s Amour is the story of an elderly couple slowing dying. The film is melancholy, and the filmmaking is mediocre. In praise of the film, TimeOut magazine said: “Amour is devastatingly original and unflinching in the way it examines the effect of love on death”. The film captures the tone of death in an allegorical sense; it’s equally devoid of life as the degenerating characters it depicts.

That said, the film is most certainly worth watching, if only for a lesson in minimalistic sound design. The first scene of the prolonged flashback – which is the main body of the film – shows the couple sitting in the fourth row at the concert of an ex-student of Anne’s.

The lengthy shot holds as the audience settles down, plunges into silence, then admires the first few notes of the performance. This scene symbolises the lull the characters face throughout the film; the moment of stillness before death, which – in an optimistic reading – is superseded by the soft music of the afterlife.

Author Bio: Ben is, first and foremost, a performer. A passion for circus performance, and the realisation of that passion, formed the happiest memories of his childhood. Consequently, audiences have always had a place in his mind; understanding audience reactions fascinated him from a young age – figuring out how to squeeze that last drop of admiration from a crowd, knowing when to pause, when to take a call, or how to deliver a punchline. This passion for performance, along with an interest in technology, and a fascination with psychology, lead him to studying Film and Television at Plymouth College of Art.