5. No Country for Old Men (2007, Coen Brothers)

No Country for Old Men is a deep Coen brothers film that, unlike many of their others, they didn’t fully write. In it, Anton (Javier Bardem), is a murderous fiend, slaying almost everyone he meets across a wide Western barren landscape, all in search of lost drug money.

Meanwhile, the sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones) witnessing these atrocities is speechless and shocked. Facing incomprehensible nihilism and its destructive powers, he cannot rationalize these acts or what the world has come to, and feels that he is completely out of place. And don’t we all.

No Country for Old Men is gorgeous. Somehow, the Coen’s manage to completely grasp and depict the West as writer Cormac McCarthy originally wrote about it, and provide such stunning and empty shots that convey a true feeling of loneliness. By this, I don’t mean of being bored and lonely and missing your friends, but rather of being alone in a wide open country and having no one to turn to for help.

One poignant shot in particular is of the highway, winding away surrounded by rolling hills. In this shot, we look down the highway until a car races down the road away from the camera (and viewers), while simultaneously the camera elevates to further show us a beautiful yet desolate landscape. From this shot alone, you can know how the film will turn out.

4. Fata Morgana (1971, Werner Herzog)

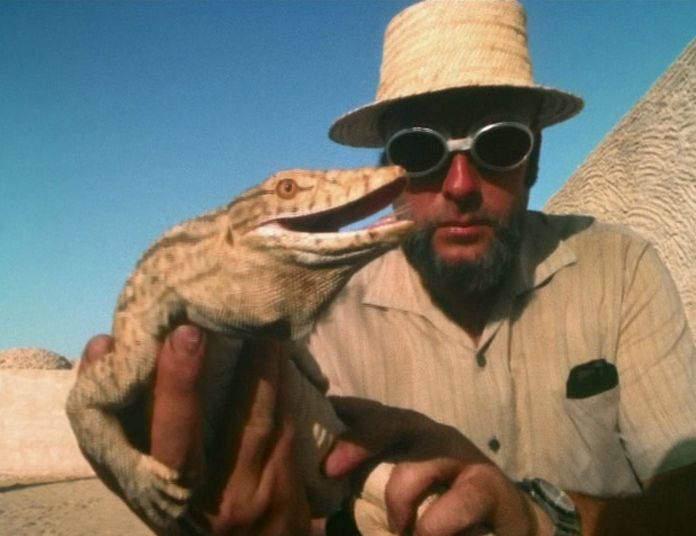

Fata Morgana is perhaps Werner Herzog’s most experimental form. Its title translates to “a mirage”, and its subject is creation and the beauty of earth. Throughout the film, we hear excerpts from the Mayan creation myth, as well as self-contradictory aphorisms.

The film is primarily intended to question creation and how things came to be, but it simultaneously questions reality and how we perceive things. Can we trust our senses or, in Descartes fashion, is everything actually a mirage or a representation of something that we can’t quite perceive? Herzog invites his viewers to ask these questions in every shot.

Herzog posted his cameraman on top of a Volkswagen van, which Herzog drove, in order to capture sweeping shots of the barren landscape. Many of the images are of Saharan mirages, which capture this beauty while directly calling reality into question.

However, Herzog also captures incredible shots of the sands and water from above which he juxtaposes with the narration to create a stark contrast, so startling it is capable of making viewers question what they’re seeing. A perfect example of this is a shot of craters viewed from afar shown while the narration talks of turtles (which these craters seem to resemble). An incredible image, but one that does not correspond with the narration.

3. Ordet (1955, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Ordet is a Carl Theodor Dreyer masterpiece (though most of his films are), which follows the struggles of the Borgen family. Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), the oldest of three children, has lost his faith, but he is married to a very devout woman who is pregnant with his child. Anders Borgen (Cay Kristensen), the youngest of the Borgens, is pursuing the daughter of a fundamentalist church leader and still discerning exactly what he believes.

And the middle child, Johannes Borgen (Preben Lerdoff Rye), is the most unique and complex—he went insane “studying Kierkegaard”, we are told, and is convinced that he is Jesus Christ. The film is ultimately an analysis of faith: how does one get it, what can one do with it, and what should one do to keep from losing it. If Christ were among us, what would we do, how would we treat him, and would we believe him?

Ordet is also beautiful, especially in its scenes of Johannes out in the countryside. When he’s left the house, he walks among flowing grasses and is depicted fully illuminated against the soft sky behind him.

Dreyer and most filmmakers of the black and white era had a better sense for lighting than modern filmmakers do, and this is apparent throughout the film. If divinity were physically among us, we would imagine it to be radiant and mesmerizing. Dreyer is able to meet this expectation in Ordet, making the film more handsome and powerful than other filmmakers could.

2. Knight of Cups (2015, Terrence Malick)

Malick’s latest film Knight of Cups has been heavily criticized and is sorely misunderstood. While it’s no Tree of Life (that level of excellence will probably never again be attainable by any filmmaker), it’s a powerful film chock full of Kierkegaard which parallels the parable of the Prodigal Son. In it, Rick (Christian Bale) is a wandering young man who has forgotten why he’s here (the reason, of course, being that he is a creature of God intended to serve his creator).

As he wanders along, he feels alone and incomplete, and is unwittingly contributing to this feeling by living a life of debauchery and irresponsibility. Yet, on paper, his life seems to be a great success, because he is a successful producer who drives a convertible, woos women, and lives in a state-of-the-art apartment.

The message: there’s more to life than what we can perceive with our senses, and if we wake up from this dream of life and realize what truly matters (our reason for being), then we can live fully and contentedly.

Like all of his others, Knight of Cups is gorgeous. Unlike Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and Bergman, it features no long sweeping shots, but rather is full of short, flittering glimpses which are edited seamlessly together. There’s so much camera movement that it gave my wife motion sickness.

Yet, this chaotic and rapid movement adds to the feeling of rootlessness that all of the film’s characters are feeling. Malick, as always, shoots pretty much only at dawn and dusk, and uses natural light in a beautiful and compelling way. The film is abstract, perhaps his most abstract to date, but it is definitely worth watching and likely foreshadows other stunning and deep Malick films to come.

1. Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky’s Stalker is a return to the science fiction genre following Solaris, but Stalker takes place on Earth and focuses on an impenetrable and mysterious zone in Soviet Russia. It is the tale of a journey a stalker (Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy) makes into this zone as an escort for a couple of desperate men. In English we might translate “stalker” to “guide”. Inside this zone, there is rumored to be a room that grants the deepest desire of anyone that enters.

It’s important to emphasize “deepest desire” here, because one’s “deepest desire” may not be the wish one thinks one wants. The central thrust of the film is to question reality and how we can determine what is real versus what is only thought to be real (i.e. a central question of epistemology).

Tarkovsky truly does an amazing job capturing the magnificence of the Soviet landscape. Particularly striking are the scenes in which the Stalker is throwing lug nuts with cloth tied to them to try to determine which areas are safe for their travel. We see sweeping shots of the landscape here, and the plants seem to be in full bloom and vibrant.

Also gorgeous are the shots of the building in which the room is located. It is believed that filming in this warehouse gave Tarkovsky cancer (which he eventually died from), and so these scenes came at a high cost. That said, they are truly beautiful and captivating, adding to the magical feeling viewers get when the characters travel through the zone.

Author Bio: Ben Wilson graduated from Yale College in 2014 where he studied Philosophy and Political Science. He currently lives in Houston, TX, with his wife Rachel, where he works as a consultant while directing his first feature-length film. If you’re interested in discussing this piece or joining his film project, please contact him.