6. Ghost Dog: The Way of The Samurai (1999, Jim Jarmusch)

A modern spin on the samurai movie filtered through the idiosyncratic lens of Jim Jarmusch, Ghost Dog wears its influences on its sleeve yet manages to stand alone as its own strange beast. At its most basic level the narrative is undeniably familiar: a master samurai, indebted to a lord, suddenly finds himself caught in the crossfires when a hit is put out on his head.

However, nothing is ever quite that normal in a Jim Jarmusch film; to complicate what would otherwise be a predictable and passable story that’s been worked to death in the past, the film takes place in New York City, the samurai is a contract killer played by Forrest Whitaker, and his equivalent of a lord is an Italian mob boss named Louie.

Whitaker’s eponymous assassin seems to spend more time studying bushido, training carrier pigeons, and waxing poetic than actually killing criminals, making the film more of a quirky delight than an ultra-violent series of deaths, but rest assured there are more than enough B-movie-inspired murders to sustain the strange and often meditative plot.

7. Bullitt (1968, Peter Yates)

It’s difficult to separate Bullitt from its legendary chase scene, and understandably so; the car chase, which spans countless San Francisco streets and lasts ten minutes yet feels like twenty, is the film’s glorious centerpiece and its most exhilarating sequence by far. It’s easy enough to make cars leap over hill-after-hill at high speeds, but never before this film had it been performed with quite so much style and filmed with such reverence.

While the film surrounding it makes for a surprisingly good crime thriller, that wildly kinetic chase scene is the reason why Bullitt is still brought up as Steve McQueen’s finest moment. Of course there is more to the film than that one sequence, and the element that most closely links it to Drive is McQueen’s cooler-than-cool performance as lieutenant Frank Bullitt.

Like Drive’s nameless protagonist, Bullitt is an antihero through and through, bending the rules and breaking the law in order to catch the criminals who assassinated a star witness in a high-profile case. McQueen plays Bullitt as an ice-cold, virtually emotionless man who stops at nothing to solve cases, and as such the character has become the prototypical “cool cop” of cinema, leaving his mark on every character from Harry Callahan to John McClane.

8. Diva (1980, Jean-Jacques Beineix)

The unofficial first film of the cinema du look – a French cinematic movement made up of stylish, visually stunning films about alienated young people in an era when most French films favored realism and restraint – is also among the best the movement has to offer: Diva is a propulsive thriller that values style over substance in all the right ways.

The film’s narrative is undeniably convoluted, with a plot that follows an classical-music-obsessed postman who inadvertently becomes the target of a corrupt police chief after coming into possession of a tape incriminating said chief in a prostitution ring, but that’s beside the point; more relevant by far are the vividly colorful visual style and thrilling action sequences, including one high-speed motorcycle chase through the Parisian subway system that Roger Ebert referred to as “an all-time classic,” and with good reason.

In true cinema du look fashion the film is pop art crossed with high art, concerning everything from opera to drug trafficking to stealing records, and the sheer chaos of it all is dazzling. There’s no arguing that the movie has little to say in terms of themes or messages to take away from it, but the abundance of style and romanticism makes any discussion of plot and depth entirely immaterial: this is as pure and hedonistic as cinema gets.

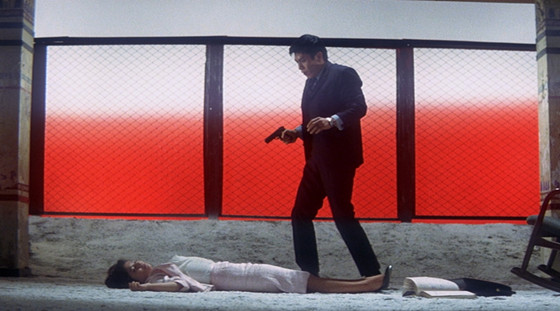

9. Tokyo Drifter (1966, Seijun Suzuki)

Never one to make a traditional film by anybody’s definition, Seijun Suzuki was an outsider even when he was working within the Japanese studio system. Widely regarded as his artistic peak during his time at Nikkatsu – Japan’s oldest and most famous studio –, Tokyo Drifter is an oddball yakuza movie inspired in equal parts by American gangster movies and the Japanese avant-garde movement that flourished in the 1960s.

While the film doesn’t have a jazz-filled soundtrack like Suzuki’s previous film Branded To Kill, it is essentially the cinematic equivalent of free-jazz: bright colors, erratic editing, and hyper-stylized violence all give off the impression of a psychedelic James Bond movie with an experimental edge to it.

The film –which follows a former Yakuza hitman who now wanders Tokyo avoiding rival gangs that seek to kill him – is outrageous and excessive by nature, but in a playfully self-aware way that only makes it all the more charming; it’s hard to resist the sheer absurdity of the film’s chaotic style, even during scenes when the editing is so unconventional that the action is obscured.

It’s a B-movie for the intellectual, combining low-budget yakuza action with bizarre stylistic experimentation in an eminently entertaining way and marking the exact point where Japanese avant-garde crosses over into accessible – but never conventional – territory.

10. The Driver (1978, Walter Hill)

This is the film most often associated with Drive, and rightfully so: the two films are identical in almost every way. Nicolas Winding Refn borrowed liberally from The Driver, lifting everything from the nameless getaway driver protagonist to the chase scenes through the streets of Los Angeles to the vivid neon color palette.

What separates this stylish neo-noir from Refn’s vision, however, is that the taciturn driver in this film – played with extraordinary nuance by Ryan O’Neal – is facing down the law, not the mob. Veteran actor Bruce Dern represents that law as the nameless detective who, obsessed with the driver à la Ahab and the white whale, aims to sabotage the driver’s operation and bring him to justice at absolutely any cost.

It’s a film made for film-lovers, employing countless tropes and devices that are instantly recognizable to devoted fans of neo-noir or westerns – the protagonist is essentially just a cross between Clint Eastwood and Steve McQueen, both of whom were initially considered for the role – but there are enough moody dialogue exchanges and spectacular chase scenes to make this easy to recommend to even the most casual viewer.

Author Bio: Joey Shapiro is a film student at Oberlin College in scenic Northeast Ohio, the cornfield capital of the world. His dream date would be watching all thirty Godzilla movies in a row.