So you find yourself at a party surrounded by cinephiles and are lost for words, unable to understand a single thing they are saying. You want to get involved in the action, add a few choice phrase and come away sounding both knowledgeable and passionate about the world of film. Yet you find yourself speechless, and with nothing clever to add.

You wonder how people become experts so quickly, and if there is a similar shortcut that you can take. Nevertheless, with so many great films out there, trying to become an expert can seem like a perilous task: where on earth do you even start?

Not to worry, as here comes help. The list compiled below works as a primer to the wonderfully diverse universe of world cinema, each entry taking on a new decade and a new country. It is by no means exhaustive, but it should help you to get a footing when your friends start going on about their favourite arthouse pieces.

By seeing how cinema varies from period to period, and region to region, and how new techniques have been innovated over time, this list should help you to fake some authority on the subject thus impressing everybody that you meet.

By generally avoiding the more obvious entries that everyone supposedly holds up as the Greatest Of All Time such as The Godfather, Citizen Kane, or Casablanca, this list will show that your understanding of cinema goes way beyond that of the average person and into the realm of the arthouse and avant-garde, in the process making you the most fascinating person in the room.

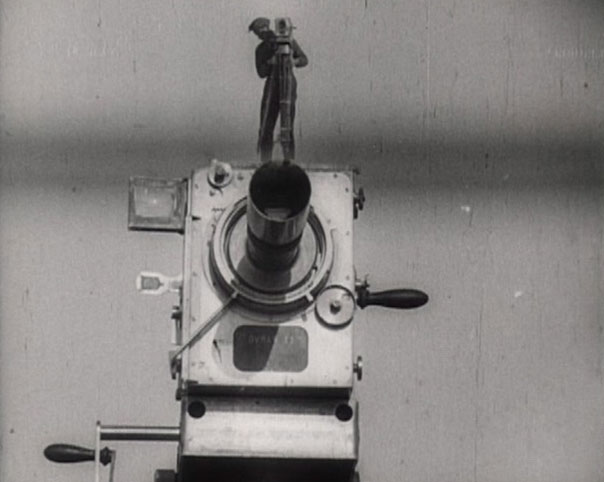

1. Man With A Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

This Russian documentary is generally considered one of the greatest ever made for its dazzling innovations in rapid-fire editing, cinéma vérité and self-reflexiveness.

Following on from prior “City Symphony” documentaries such as Paris Nothing but the Hours and Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, in which the subject is the city itself and the people who live within it, as well as Sergei Eisenstein’s seminal Battleship Potemkin, which perfected the concept of montage, Man With A Movie Camera stands as the ultimate example of modernism in film, creating a new form of expression that is unrelated to either novels, true stories or the theatre.

Simply put, it is pure cinema at its finest. Unbound by conventions of theatricality, acting, or narrative, it instead works as a freewheeling tour of Russian cities during the Soviet Era. The film is full of the seemingly mundane processes that make up the average day in Soviet cities such as Odessa, Moscow and Kiev, capturing people exercising, relaxing and shopping in a frantic montage of surreal beauty.

Yet this is no mere travelogue, instead working as a treatise on the nature of film itself, by including the cameraman as a participatory character in the movie. By removing the illusion between film and filmmaker, the viewer is able to see the method that goes behind the madness.

What is even more impressive is the lengths that Vertov and his cinematographer brother Mikhail Kaufman went to in order to get some of their best shots: including dangling from the sides of trains, teetering at the top of high bridges and descending into mines to capture the workers.

It is this almost fatal dedication to perfecting their craft, combined with its new cinematic language that makes this film still as compelling as when it was initially released nearly ninety years ago.

2. The Rules Of The Game (Jean Renoir, 1939)

If you think that Citizen Kane was the first film to deploy deep-focus — in which features in the background can be prioritised as much as that in the foreground — then think again: this style of filmmaking was already in full fruition in Jean Renoir’s The Rules Of The Game.

Renoir, dubbed The Greatest of all Directors by Orson Welles, made many fantastic films over his lifetime, including Le Grande Illusion, The River and French Cancan, yet The Rules Of The Game has stood the test of time to be his most seminal work. The context of the movie is crucial; made as Europe was about to descend into its Second World War, it starts with the famously dishonest subtitle:

“This entertainment, set on the eve of the Second World War, does not claim to be a study of manners. Its characters are purely fictitious.”

This is a lie. By satirising the feelings of the upper class at this time, Renoir creates an allegory for the liberal complacency that led to the upcoming conflict, making it as important a historical document as an aesthetically pleasing work. Much of the praise lavished upon this movie is as a result of its stylistic techniques.

As a tragicomic work, blending the ‘high’ concerns of the rich with the ‘low’ concerns of the people who work for them, the deep-focus photography gives one the sense that there is always something important going on off-screen, thus making the whole mansion feel truly alive. Rarely does camerawork flow as magnificently as this.

Released in a remarkable year that also included The Wizard Of Oz, Gone With The Wind, and Only Angels Have Wings, The Rules Of The Game might just be the best of the lot.

3. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

The plot of Bicycle Thieves is deceptively simple. A poor man, living in post-World War II Rome, leaves his bicycle outside an apartment. Next thing he knows, it has been stolen. The problem: he needs that bike in order to complete his job. The rest of the film follows him and his son trying to relocate his bike, leading to a devastating ending which basically implicates everyone involved.

That’s more or less it: but what happens in-between makes this one of the finest humanist documents to be found in cinema, never judging but merely empathising as a good man finds himself compromised by a society that has more or less broken down. Accompanied by his son, this film also savours the sweeter moments: a scene as simple as eating pizza in a restaurant truly pulling at the viewer’s heartstrings.

A hallmark of Italian neorealism — in which all embellishments are disposed of in favour of direct, no-nonsense camerawork, and which on-location shooting with non-professional actors is highly preferred — Bicycle Thieves perfectly captures the anxiety of a country still trying to find its feet after the intense horrors of WW2.

Shot on practically no-budget, De Sica demonstrates that sometimes the best stories can be found in the fabric of everyday, working-class life. It has been acclaimed as a classic ever since its release.

4. Tokyo Story (Yasujirō Ozu, 1953)

This film is comprised entirely of static shots: the camera does not move, not even once. Major events in the character’s lives occur off-screen, the ramifications of those events only revealed to us much later. Sometimes the camera breaks from the action to show a passing cloud, or someone cycling past a window. Yet such stylistics restrains aren’t a burden on experiencing the film: instead it is through Ozu’s rigid formalism that Tokyo Story garners its intensely emotional effect.

Influenced by Leo McCarey’s Make Way For Tomorrow, Tokyo Story tells the story of an old couple who go to Tokyo to visit their children, only to find that they have no time to entertain them.

Like in Bicycle Thieves, the fall out from WW2 has led to a decisive break in the culture between old and young in Japan, leading to a truly heartbreaking failure of communication. If you fail to cry by the end of this movie, and its bittersweet yet unremittingly bleak tone, then perhaps you should ask yourself if you truly have a soul.

An influence on everyone from Robert Bresson to Jim Jarmusch to Paul Schrader, Tokyo Story is the perfect introduction to the concept of spirituality in film; that through a withholding of obvious, manipulative tactics, the viewer is moved into a state of transcendence akin to the buddhist concept of ultimate acceptance. Thus bringing Tokyo Story up at any dinner party is a prime way of showing that you value cinema at its most philosophically potent.

5. Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969)

One of the key films, along with Bonnie and Clyde and In Cold Blood, in heralding in the new Hollywood era — replete with films that took wild risks and told non-classical stories — Easy Rider also holds the benchmark of being one of the coolest films ever made.

Produced, acted and shot under the influence of drugs such as LSD and marijuana, Easy Rider melded the emerging bike genre with the Western, filtering both through the avant-garde as evidenced by the French films of Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais.

Making an amazing $60 million off a $360,000 budget, the strong audience and critical response to this film helped to birth New Hollywood, in which young and ambitious directors, a lot fresh out of the war in Vietnam, were allowed unprecedented creative control over their work: a trend which continued right up until the early 80s.

It broke ground a whole four years before Scorsese’s Mean Streets by using a rock soundtrack exclusively from the era, including songs by The Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and most iconically Steppenwollf’s “Born To Be Wild”, which plays as the protagonists take their bikes to the open road.

However, most notably, apart from cementing the careers of Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, Easy Rider also introduced the world to the great Jack Nicholson, playing an alcoholic lawyer who joins the boys on their hedonistic search for the real America.