“No Country for Old Men”, the 2007 movie directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, can be seen as a diagnosis of a century in which we live. It portrays nihilism in its essential form, and of all the movies of this century, it does so most truthfully and vividly.

The film is based on a novel by Cormac McCarthy, which came out in 2005. Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 movie, “A Clockwork Orange”, portrays nihilism as well, and can be seen as a diagnosis of the 20th century. Its depiction of determinism, absence of free will, and nonexistence of values is highly relevant.

In the Coen brothers’ “The Big Lebowski”, nihilists appear; they are portrayed as eccentric and although their posture is aggressive, John Goodman’s character, who is a practicing Jew, easily beats them toward the end of the movie. He believes in something and is superior to them because of that. They are passive nihilists, and the message could be: nihilism makes you empty inside and physiologically inferior.

Friedrich Nietzsche, who died in 1900, wrote in his book “Will to Power”: “What I relate is the history of the next two centuries. I describe what is coming, what can no longer come differently: the advent of nihilism. This history can be related even now; for necessity itself is at work here.” Nietzsche defines nihilism as a process in which “the highest values devalue themselves.”

He believed that the advent of nihilism is an unstoppable process; the “preparations” for it had been taking place for decades, in art, philosophy, and history itself. Morality was a great antidote against nihilism, but those values are, according to Nietzsche, put in question; the Enlightenment failed to provide us with a substitute, thus nihilism is a logical conclusion of our realities.

He also writes: “The philosophical nihilist is convinced that all that happens is meaningless and in vain.” The spirit of a lack of meaning is omnipresent in “No Country for Old Men”, although Javier Bardem’s character Chigurh attempts to overcome nihilism and create meaning in the characters’ squandered lives, as it is suggested in the novel.

In this article, it will be presented why this film describes our reality as nihilistic, which philosophical ideas are present in the narration and in the characters’ personas.

In this context, nihilism does not simply mean “relentless negativity or cynicism suggesting an absence of values or beliefs”; the term is not directed toward the Coen brothers, let alone McCarthy’s work. It is figured as a philosophical term as it is defined in Nietzsche’s philosophy; its analysis does not refer simply to the movie’s atmosphere and brutality, it has broader implications.

1. Death of old values; nothing replaces them

When a madman in Nietzsche’s “Gay Science” proclaims the “death of God”, it does not mean simply that there is no God. Atheists proclaimed that much earlier. What it means is that old values are in a tailspin. The tragedy lies in the fact that nothing replaces them. This void that comes to being is the essence of nihilism.

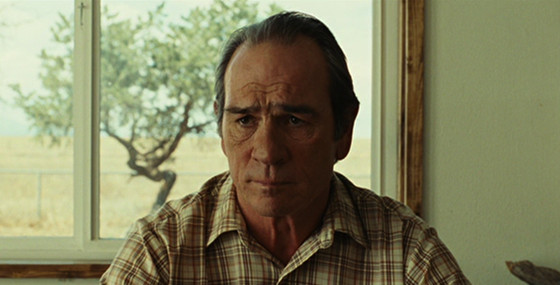

The very name of the movie “No Country for Old Men” implicates that there is no place for “old men” and old values in the new world devoid of meaning. They are obsolete. References to this idea are made at various points throughout the movie. For example, when Sheriff Bell and his colleague from El Paso discuss the radical changes in their society, the latter says: “It’s all the goddamn money, Ed Tom. Money and the drugs.

It’s just goddamn beyond everything. What’s it mean? What’s it leading to? You know, if you’d have told me 20 years ago I’d see children walking the streets of our Texas towns with green hair, bones in their noses, I just flat out wouldn’t have believed you.”

Sheriff Bell replies with a quote from the Bible: “Signs and wonders”, the verse that foretells the Apocalypse. He also says: “But I think once you quit hearing ‘Sir’ and ‘ma’am’ the rest is soon to follow.” He gets the reply: “It’s the dismal tide.”

In sum, the human life has lost its purpose and meaning, and there are no higher values that transcend “money and drugs”, the symbols of decay. One may wonder whether Bell and his colleague have fallen into a trap of idealizing the past and rejecting the present as meaningless; this is the form which nihilism can take.

Bell’s uncle, at the end of the movie, says: “What you got ain’t nothing new. This country is hard on people. You can’t stop what’s coming.” In other words, the killings and atrocities are trans-epochal, they have just taken a new form; what is new is nihilism, a lack of capability to comprehend violence and put it into perspective. Due to the corrosion of traditional values, things don’t make much sense anymore to most people, and Bell is one of them.

2. Art direction

The locations that were picked for filming beautifully depict the flood plains of Texas from McCarthy’s novel, but also highlight the main ideas of the film; a never-ending wasteland creates an atmosphere of lostness, lack of direction, and purpose. Bell’s monologue and lamentations only enhance the feeling of resignation and lost time.

Dan Flory, in his about the movie “Evil, Mood and Reflection” writes: “The directors supplement these affective tones with establishing shots of barren, southwestern Texas landscapes that follow the initial black screen, as well as by means of accompanying sounds of wind howling…

Dark and obscure landscapes, such as the predawn, sunrise and deeply shadowed morning shots offered here ‘provoke trepidation’.” The motels in which Llewelyn resides briefly are dark and sometimes claustrophobic; danger can emerge at any given time and in any place. The viewer gets an impression that Chigurh, who hunts his prey, is omnipresent; he can appear at any time out of nowhere, like a ghost.

3. Chigurh – “prophet of destruction”

Chigurh, a psychopath who commits murders throughout the movie, may be incomprehensible for the viewer. His murders seem to be illogical; nevertheless, they do have some kind of regularity and guiding principles. Carson Wells says about Chigurh: “He is a peculiar man. Might even say he has principles, principles that transcend money or drugs.”

For example, he does not kill the landlady who refuses to give him information about Llewelyn; he respects her courage to refuse his request out of her own principles. He wants to kill Llewelyn because he is an inconvenience, he is standing in his way, and also out of contempt. While Llewelyn wants money simply because he is greedy and wants to live an easy life, Chigurh wants it because he wants more power.

In his “Will to Power”, Friedrich Nietzsche defines active nihilism as a “violent force of destruction.” That is exactly what Chigurh is. He also writes: “At this point nihilism is reached: all one has left are the values that pass judgment – nothing else… 1. The weak perish of it; 2. those who are stronger destroy what does not perish; 3. those who are strongest overcome the values that pass judgment. In sum this constitutes a tragic age.” Chigurh sees himself as the stronger one and thus his mission is to annihilate the weak; those without any moral principles, whose lives lack meaningful conduct toward themselves and other people.

In his “Do You See? Levels of Ellipsis in ‘No Country for Old Men’”, Jay Ellis states that Chigurh is a Socratic figure; he wants his victims to reach a level of self-awareness. He tries to achieve it using a dialectical method, through dialogues.

This interpretation explains Chigurh’s character on many levels. He discusses their lives and tries to make them see how they ended up being his victims. In what ways they squandered their lives without being self-aware. Chigurh is one of the rare characters in the film whose actions are a product of self-examination.

The other is Bell, but he lacks the strength to create meaning and understand things that surround him. Chigurh is an example of an active nihilist, while Bell is, as Dan Flory suggests, a passive nihilist. He escapes reality, while Chigurh embraces it and acts on his instincts.

4. Human life has no value

This is best shown in the scene when Chigurh asks the gas station proprietor to call heads or tails for his life. Although a 50-50 chance of survival is better for the victim than certain death, Chigurh offers him a chance for redemption. It is clear that Chigurh does not consider his life worth living. Llewelyn’s life does not bear much value as well; he does not reflect on his actions and puts his wife’s life at stake for profit.

Considering the weapon he uses throughout the film, the cattle gun, it is obvious that human life has no more worth than that of cattle. When the sheriff tells a tale to Carla Jean about killing livestock, his point of reference are human lives. Chigurh does not value all human lives equally; some have more value, some less value, but he indiscriminately murders those who are in his way in a cold and brutal fashion.

5. People are presented as sacks of meat

Llewelyn is shot multiple times and stains of blood on people’s clothes are often showed. The scene in which Chigurh is lying in the bathtub wounded with blood all over his leg, presents him as a human being of flesh and blood. In the novel, he tells Wells that being injured changed him. He realized that he is a man too, that he can be wounded and bleed.

When people are murdered with a cattle gun, they are just expendable meat, like cow meat, which is put on the table for dinner. This reduction of sentient beings to meat can be made only by someone who denies people the rational component of their existence. Someone who does not use his brain at all, as Chigurh believes, shouldn’t be treated better than an animal. T

he scene at the end of the film, when the bone is jutting out of his arm after the car accident, shows this materialistic component that reduces people to meat.