6. Extraordinary visuals

The film is shot in black-and-white and it uses the possibilities of the technique to its fullest extent. The appearance of a ghost looks majestic, and the black hills overshadowing the scenes of carnage are mesmerizing.

The white fog that covers them symbolizes illusion and a lack of something to hold on to. Blood is black and this makes the portrayal of malice more powerful. Scarce light gives the viewer an impression that what he watches is a gothic nightmare. In one of the last scenes, from the tower of the castle, Washizu sees trees moving in a surreal fashion.

This scene is a sign of imminent doom and defeat that approaches silently, but with certainty. It is also a message that something that can be seen as impossible from one perspective, is actually entirely possible, and could happen if you change perspectives. Contrary to the Japanese practice at the time, the film almost always uses full shots. This kind of filming presents the picture as cold and almost devoid of emotions.

7. Philosophy of human condition

At the beginning of the movie, the chorus sings: “At the scene of carnage, born of consuming desire.” The Greek term “pleonexia” signifies greed and desire to possess; it is an insatiable desire for more that is potentially limitless. One of Marquis de Sade’s characters says that he wants to destroy the sun, and that is exactly what drives Washizu to murder for power.

In the other words, atrocities are committed because of the desire to become more than you are, stronger and more powerful. It is a strong moralistic message, but it also portrays the human condition as tragic. While you can attain more than you possess through your acts, and they are beneficial in the short term, in the long run you will end up worse than in the beginning.

In Washizu’s case, death is imminent. It is a circle of desire, gain, and loss that is potentially unending. The only way to escape the tragedy born of consuming desire is through virtue and modesty, and the morals of “Macbeth” are precisely that. In his book “The Films of Akira Kurosawa”, Donald Richie writes about “Throne of Blood”: “Cause and effect is the only law. Freedom does not exist… It is ice-cold.

Here, Kurosawa is making his point by allowing no hope or escape. The inner richness of Sanshiro, the heroic gesture of Watanabe – these cannot exist in this lunar half-world which is the one most of us inhabit.”

8. Depiction of descent into delusion

While Shakespeare’s Macbeth descends into madness, Kurosawa’s Washizu descends into delusion. What he experiences is not madness; when at dinner, instead of having a hallucination, Washizu sees a ghost; a supernatural interference, not “a painting of fear” as Lady Macbeth suggests in the original text. In Polanski’s or Welles’s version, it is implicated that what Macbeth sees is a hallucination, making Shakespeare’s text more contemporary.

In the original play, Macbeth sees ghosts. Washizu’s delusion is most vivid when he talks with ghosts in the Spider’s Web Forest. He says: “I’ll lay a fresh mountain of corpses over these bleached bones. A deluge of blood shall stain these wood’s crimson. Come for me Noriyasu… Bring every man you can find and lay siege to Spider’s Web!”

At the verge of defeat, he speaks the words of a man confident of his victory. His bloodlust is only comparable to the delusions in his mind. In other words, he has completely lost his compass considering what is possible and what is impossible. It is not an unusual behaviour, as tyrants and dictators throughout the history of the world have often behaved that way.

9. Entry of “common man” onto the stage

In Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood”, as well as in some of his other movies (e.g. “Hidden Fortress”), common man starts to matter, and plays an important role. Throughout the movie, common soldiers appear often, supportive of Washizu at the beginning, but in the end they are foretellers of a certain doom. Washizu is killed by his soldiers, while in Shakespeare’s play and in Western film adaptations, the fight is fought between the aristocrats only.

In Kenji Mizoguchi’s “Ugetsu”, peasants can be seen trying to gain higher posts in the feudal structure, but they fail and tragedies occur. It can be interpreted as a satire of feudal society, but also as an attempt of common man to matter and play an important role in society and history. Kurosawa, on the other hand, gives common soldiers and men a role on the stage; they are not just spectators.

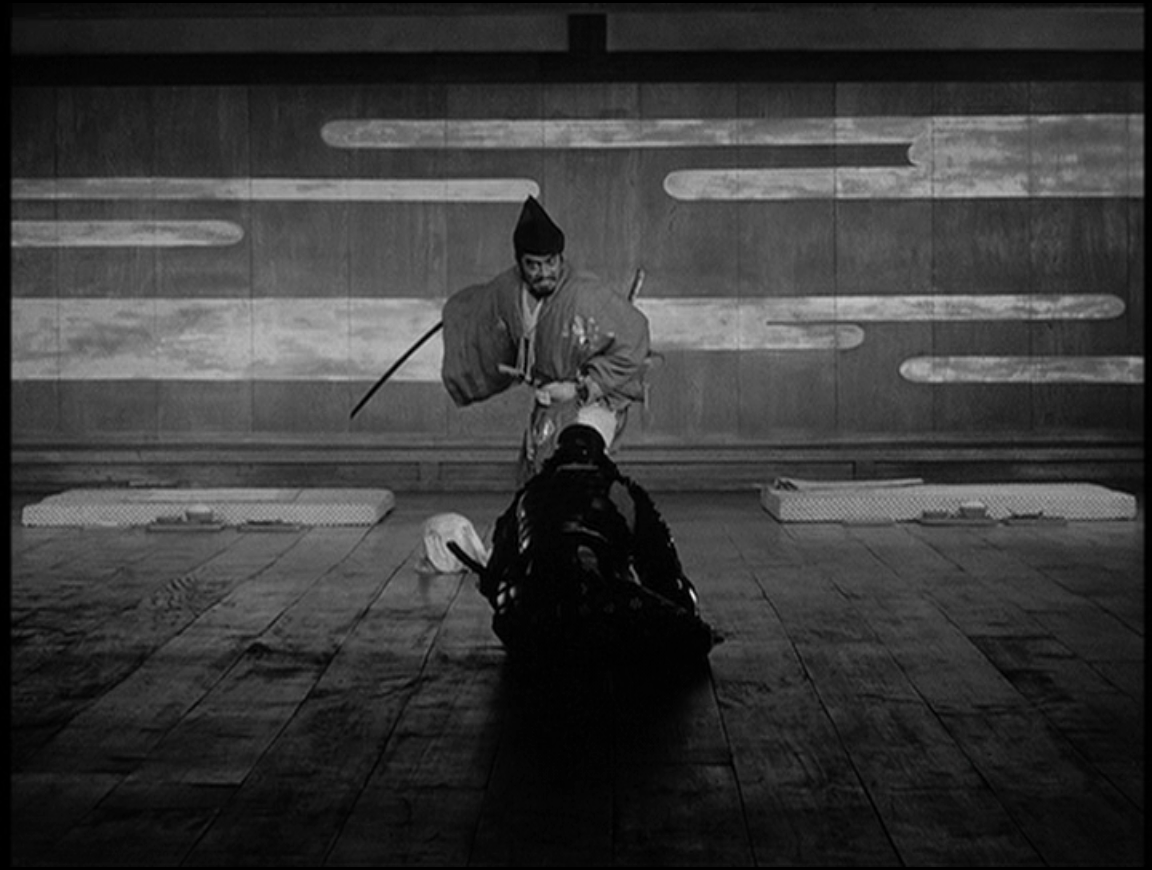

10. Memorable ending

Washizu’s death is impressive and even more violent than in other interpretations of the play. In the documentary about Kurosawa, “The Last Emperor”, the associate producer who worked on the film, Teruyo Nogami, says the following about this very scene: “It was a very risky, difficult scene to shoot.

Toshiro Mifune was scared to death! He couldn’t sleep at all the night before… But Kurosawa told him ‘Just do it!’ We lined up all the expert marksmen in front of Mifune… The arrows were pulled by strings inside, so they would hit the right spots… The farther shots were real, made by expert archers.”

When Washizu has an arrow in his neck and is surrounded by them, he is confronted by soldiers pronouncing his guilt; the moment is marvelous. The film ends as it begins: with a chorus. This kind of envelopment has great effect. It is simple, but all too powerful.

Author Bio: Hrvoje Galich is a student of political science and writes expressionist poetry. He believes that Tristan und Isolde is the most beautiful artistic piece in the history of man. He loves movies by Andrei Tarkovsky, Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman and Shohei Imamura. He adores his cat “Meow”, the only cat in the world that can say her name.