Is it possible for a person to not only filter his thoughts through a film, but also to manage something that is “other” from him, unexplainable through the conventional notions of meaning and sense that are common to society?

To do the impossible and escape the cages of human perspective and achieve a point of view that is inhuman, devoid of the universally agreed upon notions of meaning? Impossible to reconduct to an arid and rational scheme?

To Gilles Deleuze, becoming, passage, time passed, the merging of the bodies together creates meaning, and this is best exemplified in art in general, and in cinema, as we are in a constant fight between the virtual and the actual. Art is an abstract machine that can construct and deconstruct meaning, by subverting and revealing.

Cinema is the inhuman eye that constructs human meaning through duration and the display of time in its flow and its emergence. Time and space and their filmic interpretation, and the relationship between the two, create what we perceive, without a doubt, to be a cinematic vision.

So the cinematic eye is separated from the human eye, even if these two elements are in constant communication, and therefore cinema can give birth to something that is effectively inhuman.

Deleuze also says that we can escape the vision, because, for example, Samuel Beckett’s experimental film, eloquently called “Film”, shot in 1965, escapes the vision through the representation of “blackness, darkness.”

Jonas Mekas also spoke about the tyranny of mainstream cinema and how the experimental tradition tries to approach cinema as a representation of mental states that happen on a pre-speech level, that have more in common with James Joyce and Lewis Carroll than a representation conceived as conventional.

Some experimental films try to create something on screen that makes the nonsensical, the incorporeal sense, the structure outside the meaning that Deleuze calls skindapsos, come alive in the form of purely impulsive, emotional, undefined states of matter and thought.

The manipulation and subversion of time and space create a sense of detachment that makes the film look inhuman, like an alien object, something that is to be perceived as distant and different when it is in fact a pure river of cinematic intuition, a flow of life in images, confusing in its otherness.

The creation of an inhuman perspective is also a very effective way of dealing with transcendent subjects that escape the human perception and need a great deal of abstractions and philosophical detachment to be faced, like the notions of memory and time, what it means to be human, otherness, subconscious, nonsense, divinity, and the structure of reality itself.

Ten films, ten explorations, ten daring experiments, ten interstellar objects that are not from this planet, an alien consciousness.

10. ID (Mara Mattuschka, 2003)

Mara Mattuschka’s short film is a perfect example of spatial subversion, creating a world where the fluid perception of the dimension of space and the nature of the human body are challenged and subverted, giving shape to a new reality where the limitations of the human form are removed and the possibilities expanded.

The film starts with a conventional representation of a bourgeois woman on an escalator, but through the use of camera movement, the woman and the audience become incapable of distinguishing whether the escalator is going up or down.

The abstract sequence that follows sees the woman plunging into a new inhuman world of depths, where her body is transformed into a viscid humanoid alien body that substitutes her skin. In this world there is no up or down, only a pool of mysterious magmatic substance and another humanoid being.

The film is deliberately provocative and also uses elements of farce and nonsense to tell its story. To make sense of it, Freud and Deleuze can be invoked; Deleuze says in its theory of the body without organs, that the body, in perennial evolution, is disposable to become anything, and this would represent the weird metamorphosis the protagonist undergoes; a scene of a human mating with its otherness, the complete union of two differences.

On another level, the title “ID” suggests that Freudian ideas are deeply connected to the meaning of the film; the Id represents the instinctual drives of the subject, the part of the psyche that is uncontrolled, and has to be controlled by the superego in order to function properly.

The sinking of the woman into a deep darkness could be the penetration into the realm of pure uncontrolled desires, animal instincts, a land where the absurdity and the confusion of the unorganized impulses escape human comprehension.

The visions and the noises can create a sense of repulsion, the same repulsion we have for desires in other animals and our own submerged sexuality, but also looking into an “otherness” that we struggle to face and comprehend.

Mattuschka manages to infuse her film with a truly inhuman soul that’s at the same time physical and abstract, a metaphor made of flesh, weird skins, protuberances and boiling liquids.

9. Alice (Jan Svankmajer, 1988)

Jan Svankmajer took inspiration from the books of Lewis Carroll, one of the greatest explorations of the paradoxes of sense in Western literature, and added his own surrealist, horror twist to create a film that puts the real and the unreal in front of one another without giving a preference, and revealing how reality is just a matter of representation, and the way the intellect combines the elements that inhabit a world.

The surrealism and the nonsense don’t become ways to amaze the viewer and exercises of imagination, but the true fabric of the reality the film portrays.

Space and time become arbitrary, as do the combinations of beings that merge together to form new creatures, the cinematic language is altered, and the relationship between signifier and signified is no longer immediately grasped by the audience.

The world of Svankamjer’s “Alice” lacks what we perceive as sense and coherence; the stop-motion animations, the transformations, and the characters entering and escaping the frames in an almost inconsequential fashion, create one of the greatest worlds of nonsense in cinema, something that cannot be explained by its meaning but by its meaninglessness, and because of this, it surpasses and redefines perceptions of the human gaze in cinema.

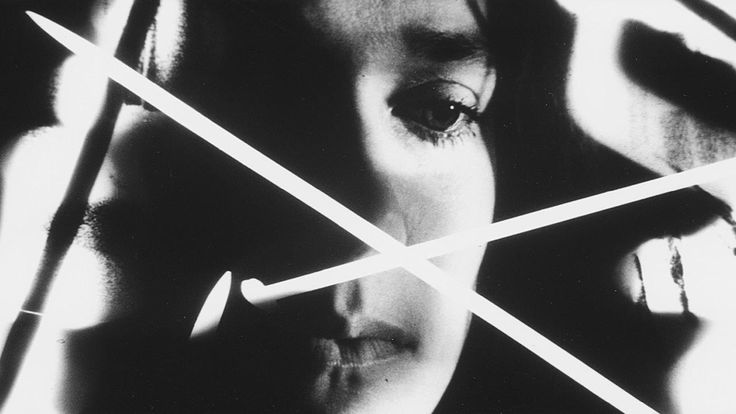

8. Dreamwork (Peter Tscherkassky, 2002)

What happens when the walls of reality crumble? Is the dream world a real dream, or is life a dream that we do not know we are dreaming? The Austrian avant-garde filmmaker has a brand of cinema that is defined as “structuralist,” that is produced from film and then developed in a dark room to achieve multiple effects.

Through an incredible cornucopia of images flashing on the screen, weird spectral games of light, industrial noises, and decaying film, Tscherkassky takes the viewer in that realm between the dream and the conscious state, a world that no one can inhabit but cinema.

The film is a prime example of the inhuman eye of cinema, an eye that can go beyond any limitation of the human cognitive experience, and re-create a cognitive state that is precluded to the human senses, giving life on the screen to something that really escapes the boundaries of the human.

Even if cinema can take viewers to the moon in other worlds, Dreamworks dares to alter the perception that the eye of cinema shapes. Tscherkassky’s odyssey is the crowning of the Kubrickian space odyssey, the voyage through the dimensions of time and space to the formation of a new consciousness, a new form of perceiving.

7. Hard to be a God (Aleksei German, 2013)

This is a science fiction film shot from the point of view of God. Aleksei German’s last film, his personal testament, is an enormous exercise in cinematic world-building that shares the cold stare of Tarkovsky but with an even more vertiginous ambition in the representation of the planet where human astronauts arrive and observe the life of the inhabitants unfold without intervening.

German uses long tracking shots to put the audience in the role of an impassible being that observes the chaotic and brutal events that take place. There is no voiceover or other trick to get the audience engaged and ease its understanding; the film is a pure image that grows and breathes, that lives on screen with no interruption and no boundaries.

This a fully realized vision of the existence of conscious beings, intellectual beings, violent beings, a swarming mass of creatures in a dirty and chaotic world. German achieves impassibility, putting the viewer in an ultra-terrestrial position of pure, distant observation.

The insensitive gaze of the film does not participate of any emotional state; all that’s left is a pure, visceral witnessing of a film that seems to have a life of its own.

The thing that makes “Hard to be a God” a unique, extraterrestrial film is that it treats the viewer like an alien and challenges him to have an elevated perspective of the events, to not be attached but detached, not human but divine, not a direct protagonist but a silent observer. It is a film that keeps the viewer away and in doing so, enables him to have a new, supreme perspective.

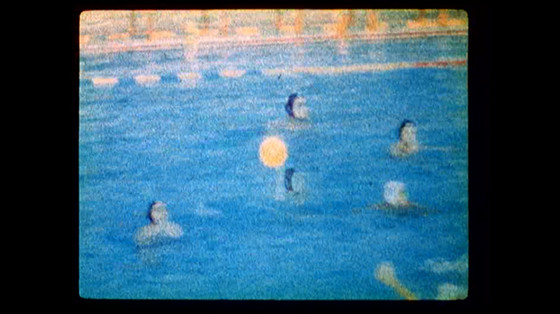

6. Water Pulu (Ivan Ladislav Galeta, 1988)

Memory is a strange thing, and French poet Chateaubriand said the world is essentially remembered. Ivan Ladislav Galeta takes an approach to showing an old water polo game that draws a musical comparison with William Basinski’s “The Disintegration Loops”.

Galeta ventures into the realm of the half-remembered, and he shows the events as a flame that is soon to be extinguished, a dying moth. It is a reflection of how memory and time corrupt reality, a journey into the disappearing, taking the viewer through his own broken memory, a journey made possible through the ultra-saturated, almost decomposing footage.

When a human looks at time, he can’t see it, he only sees things that are in the dimension of time. Galeta shows us time in its flow, through a deceptively simple device, and reaches an inhuman and extremely transcendent point of observation.