In the century since his birth, George Orson Welles has come to embody the definition of a misunderstood genius. A well documented prodigy of stage, radio, and film, his career would ultimately take a path of obscurity and unpredictability, falling far from the carte blanche infamy of his Hollywood origins.

For a great many decades, Welles was simply the man who made Citizen Kane (1941) and vanquished behind the shadow of squandered potential. Fortunately, however, that narrative has come to be eradicated in recent years, thanks to reevaluations of his work and the kindness that time typically instills upon renaissance men.

Great directors were a dime a dozen during Welles’ peak years, with an abbreviated list including the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, and Frank Capra – but few were able to shift the culture to the extent the Illinois native did during his four decades behind the camera.

Equal parts showman, technical whiz kid, and foreseer of the eminent future, Welles carved out one of cinema’s truly influential resumes, one that clocks in at just over ten feature length films.

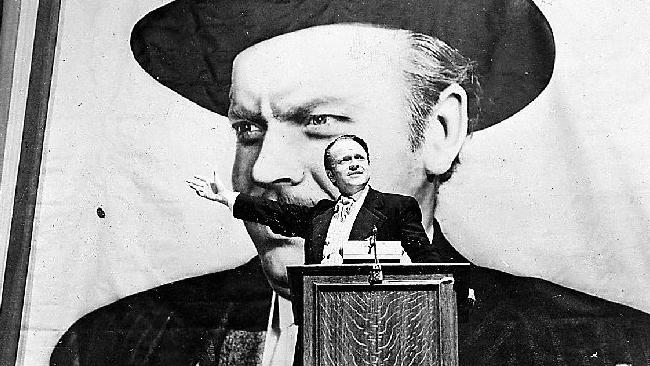

But as one to constantly derive strength from weakness, each project brings with it an evolution, a revolution, and a resolution to what the medium of moviemaking could truly achieve. So whether viewed as a Shakespearean wunderkind or a portly cigar chomper, here are 10 ways Orson Welles changed the game.

10. He maintained the showmanship of theatre

Welles’ stage history practically outshines his film career, especially when discussing The Mercury Theatre era or an all African American adaptation of Macbeth (1937) that he often deemed his greatest artistic achievement.

This success, punctuated by a now infamous air of pompousness, made the twenty-something a household name on Broadway. His productions consisted of setting fire to the rulebook and following any creative whim that was conjured up, including a contemporary version of Julius Caesar (1938) set it Fascist Italy.

Once Welles made the leap to filmmaking, this flair for the dramatics only grew within the limitless boundaries of the medium. Visionaries like George Melies and Fritz Lang laid the groundwork, but Welles brought moviemaking into the modern age with grandiose performances from both actors and technicians.

The now famous dinner table scene between Kane and his first wife is a masterclass of storytelling through deceptive simplicity, implanting stage restrictions and the trickery of film to condense decades into a single compelling sequence.

As his career went on, this penchant for flamboyance would continue to be his greatest ally, especially when faced with budgetless productions like Othello (1952) and ‘F’ For Fake (1973). The latter project, an early form of the film , is one of the most effortlessly mythic experiences ever captured onscreen, as Welles tackles forgery and immortality with all the panache of a seasoned magician (which he actually was).

In this, his final completed project, Orson waxes poetic against the backdrop of an authorless cathedral, musing the meaningless of art and his own legacy when death makes it’s final approach; simultaneously personal and of the highest possible showmanship.

As to where the truth behind the man and the myth separated was never truly divulged before his 1985 death, but, in a way, it seems all the more appropriate. Now, filmmakers can break the 4th wall, narrate their own stories, and condense time with the sophistication of an audience who’s seen it all before.

9. He was a quadruple threat

Afforded a luxury that often eluded other struggling filmmakers, Welles possessed the ability to not only direct, but to act, write and produce. And while it undoubtedly strengthened earlier efforts like Kane, this array of talents would find its greatest benefit in extending Welles’ Hollywood career come the mid 40’s.

After the editing debacle of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and the uncompleted documentary It’s All True (1942), the wunderkind was now a blunderkind, labeled box office poison by the powers that be in show business.

Consequently, the struggling auteur found his only refuge in the paychecks offered up by acting gigs, going on to elevate pictures like Journey Into Fear (1943), Jane Eyre (1944), and The Third Man (1949) through his kingly charisma. Though considered a liability at the time, the latter two films have ironically come under speculation as to whether they were ghost directed by Welles, an indicator of his overpowering presence.

Regardless, these roles not only provided the finance to back the director’s struggling projects abroad, they showcased just how impressive Welles could be in front of the camera; a pattern that would extend with turns in The Long Hot Summer (1958) and Compulsion (1959).

Outside of the performance aspects, Welles, a walking encyclopedia of Shakespeare and science fiction, reveled in the vices of mankind when crafting his scripts. Much has been documented about his visual prowess (and will be later in this list), but the quadruple threat also possessed a knack for creating characters of immense depth and conviction.

From Hank Quinlan’ swan song soliloquy in Touch of Evil (1958) to Harry Lime’s self-penned speech in The Third Man, Welles could write with the best of them; and, along with Charlie Chaplin, set the bar for which all other creatives still strive for.

8. He integrated architecture into his storytelling

This one may seem a bit outlandish, but truth be told, it was an aspect of filmmaking that Welles used to his undeniable advantage. Similar to the costumes and performers themselves, the surrounding environment is crucial in establishing the mood of a scene, something the director took quite literally from day one.

Much of this can be spotted early on in Kane, most notably through the catacombed coldness of Xanadu, but also the spacey libraries that reporter Jerry Thompson (William Alland) navigates throughout his investigation.

Consequently, the burrowing isolation behind each carefully chosen building adds to the film’s overall tone, feeding the same flavors to both the conscious and the subconscious.

It’s a neat trick, and one that would only grow with each subsequent release. Ambersons, set at the turn of the century, finds Welles stirring baroque architecture into his tale of crumbling family life, complete with winding staircases and a set design that would influence everyone from Martin Scorsese (1993’s The Age of Innocence) to Baz Luhrmann (his entire career).

One could apply this rule of architecture to each of Welles’ films, from Touch of Evil’s expressionist hotel to Macbeth (1948), which looks as though it were the precursor to Where The Wild Things Are (1963), but a truly notable use of environment onscreen arrives in the form of Othello.

Filmed in nine different cities between Morocco and Italy, the film cobbles together a jaw dropping compensation of mediocre acting and poor dubbing with a clinic in visual acuteness. Forced to craft a jigsaw puzzle of design, Welles creates an anachronistic period piece without a period, as if set in a time that never truly existed.

As a result, each scene out shadows it’s performers through grating pillars and symbolically sealing water canals, flipping a weakness into a profound strength. In his wake, similarly compulsive filmmakers Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, and Terrence Malick would craft entire careers out of this meticulous practice.

7. He directly influenced the French New Wave

The history of the French New Wave is notable for being the first bunch of filmmakers who grew up idolizing other directors. There was Francois Truffaut with his devout praising of Hitchcock, Jacques Rivette’s inkling towards Nicholas Ray, and Jean Luc-Godard’s fandom of Howard Hawks; each direct influences once the criticism turned into actual cinema.

But Welles was something altogether distinct for the Cahiers du Cinema bunch, as Godard shamelessly stated “all of us will always owe him everything” in terms of moviemaking distinction. Not surprisingly, the group pulled great confidence from seeing a legend like Welles screwing with the status quo in the 1950’s, most notably with Mr. Arkadin (1955) and the previously mentioned Touch of Evil.

Welles’ insistence on long takes, choppy editing, and an overall messiness with his craft struck a match a France, who had been appraising his works ever since Citizen Kane essentially jumpstarted the film critique of Cahiers founders Jean-Paul Sarte and Andre Bazin.

From a technical standpoint, many of the stylistically sophisticated choices made by Welles can be seen explicitly in the works of Truffaut and Godard, who used the film as confirmation for their auteur theory in Hollywood. Truffaut, in particular, was so struck by Touch of Evil that it inspired him to write the screenplay for his seminal film The 400 Blows the following year.

So while both Arkadin and Evil came and went with the waves of financial success, their powerful presentation struck the chords of young filmmakers across the world, right before the New Wave explosion of the 1960’s. Ironically, it would be Welles who would pay homage in return when it came time to craft ‘F’ For Fake, using the same messy tactics as his European peers.

6. He expanded the language of editing

In continuing the conversation with ‘F’ For Fake, the film, while similar to the New Wave in it’s uber-cool approach, made colossal strides in the fields of editing and image manipulation.

Potentially affected by the self-cannibalizing cinema of Ingmar Bergman, particularly 1966’s Persona, Welles pushes the very definition of the word “edit” by continuously building up and tearing down imagery in a scattershot manner. It’s at this point in the project, after seeing Welles at an editing controller several times over, that the realization hits that these deconstructive cuts are not idle sloppiness, but part of the actual narrative.

By 1973, most boundaries had been pushed within the cinematic landscape, save for the very presentation of the images themselves.

As a result, Welles took the last vestige of the medium and jam packed with enough imagery to earn the title “attention-deficit” editing. Though ignored by the masses upon initial release, the public would eventually catch up with the style come the 1980’s, as montage happy directors like Tony Scott, Sylvester Stallone, and John McTiernan dovetailed it into a blueprint for action cinema.

To be fair, however, this was not the first time Welles pioneered editing techniques to fit his narratives, as shown in The Lady From Shanghai (1948) and Touch of Evil. As to whether it was all the director, or the studio’s wacky attempt to recut his films into something coherent remains to be seen, but what can be seen is the tremendously sickening edits that both final products possess.

Especially Shanghai, which was slashed down from 155 minutes to 87 minutes, while still retaining what critic Pauline Kael referred to as “the dramatization of the technique of cinema,” referring to the elaborate jump cuts, doubling up of the frame, and sudden smashes into extreme closeups. It was yet another failure, despite going on to influence the entire framework of film noir moving forward.