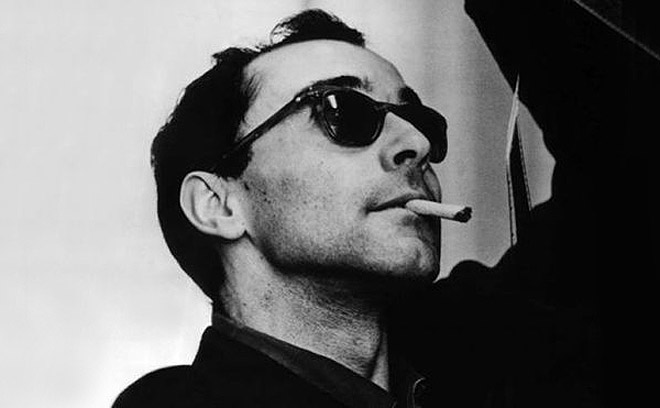

Jean-Luc Godard is one of the most well-known figures of La nouvelle vague, or the French New Wave. Filmmaker, screenwriter and critic, he started as a writer for the influential Cahiers du Cinema, like Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivettes, Eric Rohmer and Francois Truffaut, who are also influential directors of the movement.

Andre Bazin, the theorist and co-founder of the magazine, also had a great influence on the movement, so the Cahiers equipped Godard with all the theoretical knowledge he needed to get more involved in the movement. As a critic, he wrote about the “Tradition of Quality” style of French cinema, pleading for more filming on location and a more experimental style in film.

His formation as a critic influenced his style all through his filmography, as Jean-Luc Godard is one of the directors that re-invented himself the most times, experimenting with the film narrative and film form, challenging its boundaries and his own style’s commodities.

1. Breathless (1960)

Godard’s first feature, Breathless is also his most commercial film, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo, who later became one of the most popular actors of the French New Wave movement, and Jean Seberg, whose pixie haircut became iconic after the film’s release.

Starting as a gangster film and becoming a romance film as the plot develops, Breathless breaks the rules of storytelling as the audience knew them before – jump cuts are added to the editing, breaking the fourth wall isn’t a taboo anymore, the soundtrack isn’t restricted to the sound of a certain genre, and the narrative jumps easily from one genre to another without offering as much information about the story as the audience was used to receiving.

Even if the film starts with a crime, its main focus is the relationship between the main characters and their intimacy. Following their romance, Breathless starts a pattern that will exist all through the director’s filmography – lovers torn by different goals and views of the world. As Godard himself said, all you need for a good movie is a girl and a gun. Breathless is a great example.

2. Vivre sa vie (1962)

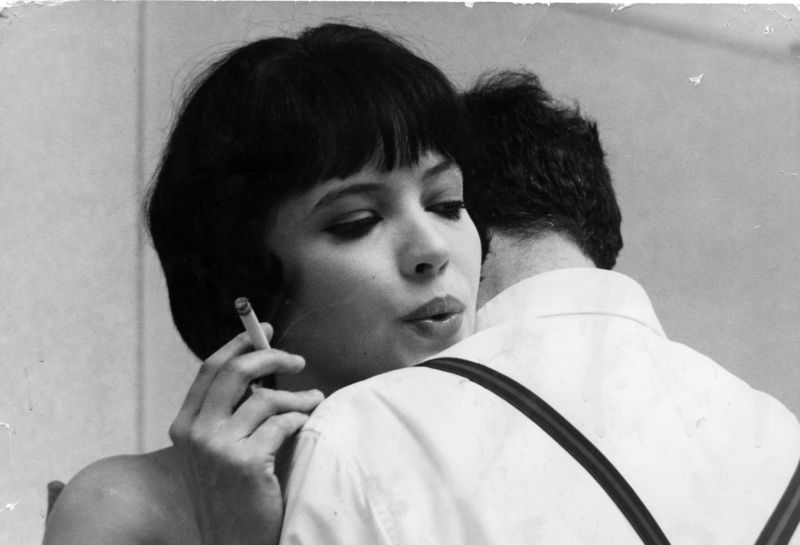

Vivre sa vie is Godard’s second film starring his 1960s muse (and wife), Anna Karina. Split into twelve characters, separed by intertitles that will become iconic for the director’s auteuristic visual style, the film follows the story of a young girl who becomes a prostitute, learning unpleasant truths about the world.

The most iconic scene of the film is the cinema scene, where Nana (Karina) cries while watching The passion of Joan of Arc, the repeated juxtaposition between Maria Falconetti (Joan of Arc) and Nana creating a parallel between them that is symbolic for the story.

3. Contempt (1963)

Starring Brigitte Bardot, the femme fatale of the French film in the 1960s and with a symbolic appearance of director Fritz Lang in a secondary role, Contempt is a film about the conflict between art and business in the industry. Camille (Bardot)’s husband is working in the production of a film based on Homer’s The Odyssey, symbolizing the era in which film was more an art than a business, but conflicts appear and the film suffers changes in order to be more successful.

Fritz Lang, iconic director of the silent era, known for his Expressionist works, is a filmmaker Godard expressed his respect for, so his role in the film has a symbolic role in its meaning. Camille’s growing contempt for her husband, as he gradually gives up his artistic wishes for commercial value, seems to be that of the director.

Jean-Luc Godard often creates films that focus more on the intellectual ideas and concepts behind the story than the story itself, and Contempt is a perfect example, as its narrative is a visual monologue about the film industry and the way it turns its back to the artistic ambitions it used to have.

4. Bande a part (1964)

Bande a part is arguably Godard’s most iconic film from the 1960s, especially after Bernardo Bertolucci’s The dreamers (2003) brought it back into the attention of young cinephiles. Anna Karina finds herself starring again between two male counter-parts, like she did in her first film with Godard, Une femme est une femme (1961), playing the cliché manage a trois of French cinema. If the 1961 movie was a comedy, however, Bande a part is far from being one.

Featuring both a girl and a gun, the film follows the story of Odile (Karina), who is invited by Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur) to commit a robbery in order to take a break from the routine. Odile, a lonely girl very fond of going to the cinema, gets lost in the action that she arguably saw as something from a film rather than an actual robbery – until it was too late.

5. Alphaville (1965)

One of the first films of its kind, before films like Equilibrium (2002), Alphaville is a dystopian science-fiction about a society located on a different planet, where emotions are forbidden. Godard makes an ingenious criticism on the functions of language: when an emotion becomes forbidden in Alphaville, the words that describe it are removed from the dictionary, and the always updated dictionary serves as the society’s Bible.

The film follows the story of a young woman from Alphaville who breaks the law, falling in love with the American detective who was there to investigate her planet. With a Film Noir aesthetic, featuring the unmissable femme fatale (Anna Karina) and a detective (Eddie Constantine) with a cold appearance, Alphaville is another one of Godard’s about art, this time the art of words and their power to support reality.

6. Pierrot le fou (1965)

After the dark aesthetic of Alphaville, Pierrot le fou comes as an explosion of color. Jean-Paul Belmondo once again plays the madly in love man in a film about a gangster and their love interest, but this time the gangster is the girl (Anna Karina), and he can’t refuse running away with her. Coloured by many similarities with Breathless, Pierrot le fou breaks all narrative expectations as it follows the protagonists down the road of self-destruction, with colourful explosions – both in the figurative and literal sense.

The film Two in the wave (2010), a documentary about Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, explores the parallel between the aesthetic of Godard’s films and the decline of his relationship with Anna Karina. After Une femme est une femme, the first film they worked together on, the aesthetic of their films becomes darker and darker, culminating with the gloomy Alphaville – immediately followed by the bright Pierrot le fou and, later, Made in U.S.A. (1966).

According to the parallel the documentary proposes, this shift in the mood of the film is far from suggesting the relationship between the filmmaker and his muse started again to move upwards – proof that they divorced in 1967. Instead, the colourfulness of those two last films they made together is a way to celebrate the past of their relationship. In this sense, it’s interesting to note that Pierrot le fou ends with both lovers dying.

7. Masculin feminin (1966)

Masculin Feminin is Godard’s first film to give a clear political direction in Godard’s filmography, after Le petit soldat (1963) gave a hint in this direction but wasn’t followed by films with clearer political messages. Paul (Leaud) has just finished his mandatory military service, and through his interactions with people around him, especially his girlfriend, who is a pop singer, the film draws observations and criticism about the youth culture of France at the moment.

The opposition between the protagonist’s beliefs and those of the youth around him is described in the intertitle “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”. The fact that the film is starring Jean-Pierre Leaud, the muse of Godard’s good friend Francois Truffaut, is somewhat ironic, as the director’s turn to politic film will mean the end of his friendship with Truffaut.