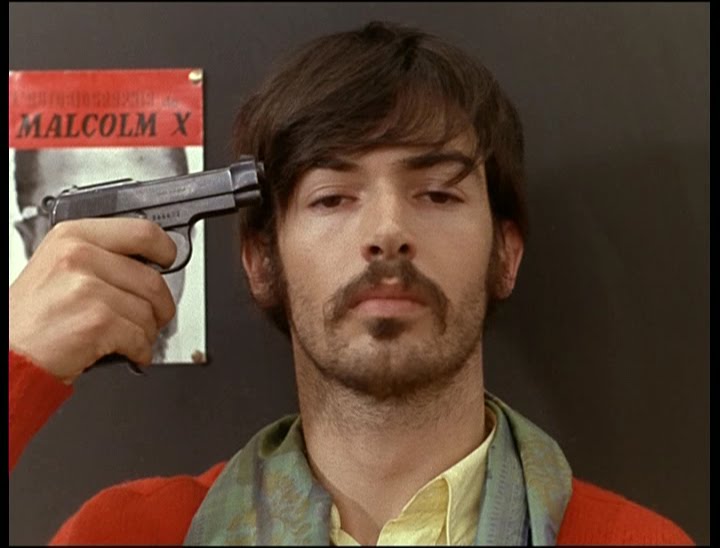

8. La chinoise (1967)

Starring Jean-Pierre Leaud and Godard’s new wife and muse, Anne Wiazemsky, La Chinoise is Godard’s first radical political film. The plot follows a group of French students who are studying Mao, looking for ways to change the world according to his theories through terrorism.

The nature of the film is more obvious than any time before, as the main plot is pure political theory, and the story is a mosaic of subplots. This film is the first in a series of radical political films that separate Godard from other French New Wave filmmakers, as his ideology distances itself from that of the movement.

9. Weekend (1967)

Released the same year as La chinoise, Weekend is a political satire about the French bourgeoisie – following a couple in their trip to the countryside, the film blames their consumerist behavior using traffic jams, cannibalism and murder as metaphors for the French society of the time.

Its narrative structure is more fragmented than La chinoise’s, so the film appears rather like a series of short allegorical rather than a continuous story.

10. Tout va bien (1972)

Tout va Bien continues the tradition of political films made in a very colourful manner. If La chinoise was dominated by red, given the importance of Maoism in its plot, and Weekend by primary colours, Tout va Bien’s aesthetic creates a French flag – blue, white and red, from the very Godardian intertitles to the mise-en-scene and cinematography.

The plot is centred around a strike at a sausage factory, creating a parallel between the workers and the couple that witnesses the strike – an American reporter and her French husband, a commercial director. Through this parallel, the filmmaker creates a visual about class struggle.

Part of the film is shot like a documentary, characters talking directly to the camera as if they were interviewed, delivering opaque performances in order to put the accent on the political message rather than the artistic value.

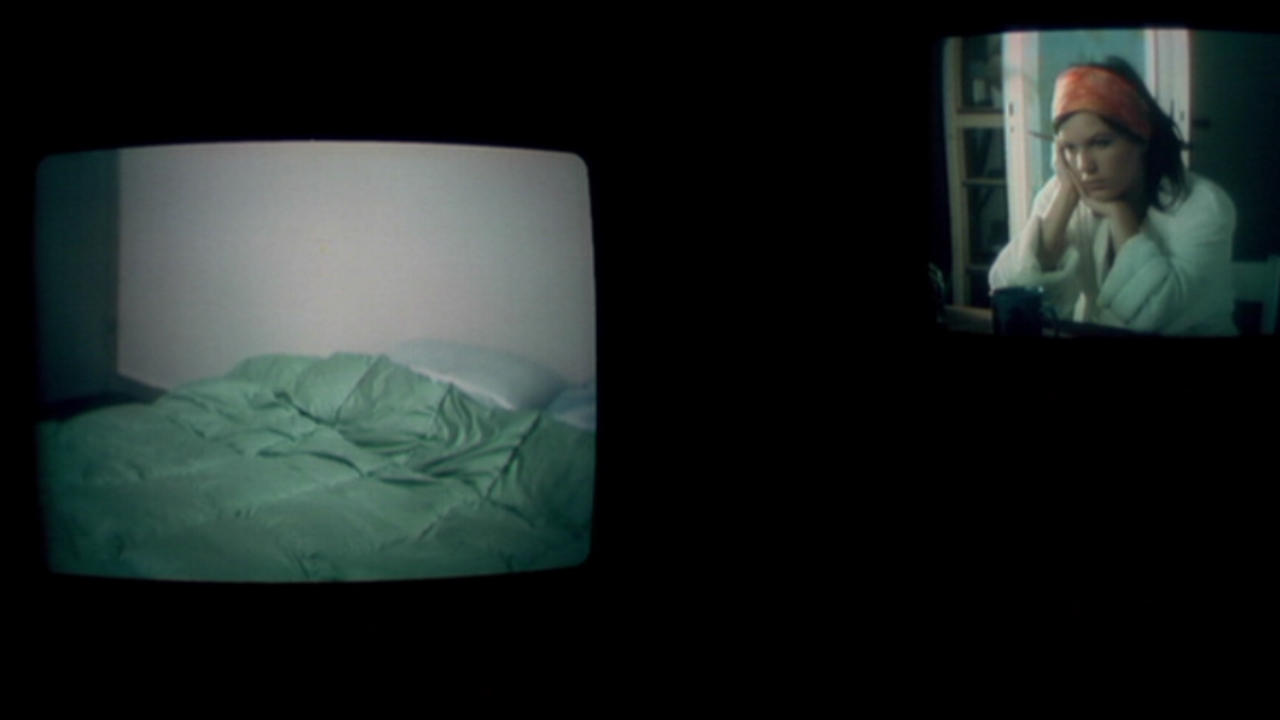

11. Numero deux (1975)

Numero Deux is the first film to feature something that Godard will use often in his future films – monologues from the director. The film is separated in two parts: the first part is a monologue from Godard, in the editing room, about filmmaking, the economics of the film industry and the way creating films isn’t very different from working in a factory where you are both the boss and the worker.

The second part of the film presents the life of a middle-class family – the characters talk about their daily life, exploring their routine and sexuality through words and images that appear on screens in the editing room from the first part of the film.

Still featuring radical political elements, Numero Deux is more a film that reflects on its own medium, suggesting the start of the experimental era in Godard’s filmography. The director has always experimented a lot with his medium, bringing new elements to the art of cinema, but from this point on his approach becomes more radical than before. If Breathless challenged the way the audience perceives genre, Numero Deux challenges the very definition of film.

12. Prenom Carmen (1983)

With Prenom Carmen the director returns to his old saying – “All you need for a good movie is a girl and a gun.” Reminiscent of Pierrot le fou in terms of character archetypes (the femme fatale, now a terrorist, and the sensitive male counterpart), the film connects Godard’s 1960s era with his later, more radical films, filling the void between the French New Wave films and his abrupt turn to political film.

As Godard’s work has always been influenced by his muse at the moment, the change his 1980s films, starting with Prenom Carmen, can be somewhat related to the fact that he re-married, his current muse being Anne-Marie Miéville – who wrote the script.

The plot follows Carmen (Maruschka Detmers), member of a terrorist gang, who falls in love with a police officer (Jacques Bonnaffé). She manipulates him, dragging him down with her. The action is intercuted with images of a string quartet practicing Beethoven, the soundtrack adding depth and meaning especially to the scenes that present the intimacy of the two protagonists.

13. Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-1998)

Histoire(s) du cinema is a series composed of 8 short films about the history of film and how it relates to the 20th century. They are created with juxtapositions between images, tests, fragments of films, monologues of the director and sounds from inside or outside the films that are showed.

Considering the 8 parts together a single piece, this particular piece in Godard’s filmography showcases more than any other his affinities as a film critic and his abilities as an ist – traits that are suggested by all his films, but never reveal themselves fully. Creating this piece allows Godard to keep evolving and develop a new, experimental yet continuous, style for his films after 1990.

14. Film socialisme (2010)

Film socialisme is a symphony in three movements. The first movement (chapter) is set on a cruise ship, featuring multi-lingual conversations between characters from all across Europe, like a modern Babel tower. The second movement is a dialogue between two kids and their parents, including questions about liberty, equality and fraternity, the values on which the French nation is built. The third movement shows visits to historical places: Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Hellas, Naples and Barcelona.

The film is a commentary on French national identity in the context of Europe, as well as a commentary about the social and cultural diversity of the continent and how it impacts individual nations. Returning to his love for political films, but taking a rather poetic approach instead of the radical approach he used back in the 1960-1970s, Godard creates a film that is very rich in terms of the themes it explores.

15. Goodbye to Language (2014)

Goodbye to language is Godard’s first 3D film. The story follows a couple having an affair, in two different yet very similar versions portrayed by two different pairs of characters.

The actions of the couples parallel each other, as the classic Godard gun is replaced by a knife that both couples use in their own way, while having conversations about art, literature, social and political issues. Parallels between couples is a very interesting pattern in Godard’s filmography, both in the same film and between a film and another – for example, the earlier drawn parallel between the couple in Pierrot le fou and the couple in Prenom Carmen.

Another interesting aspect of the film is the monologue of the director, about the relationship between humans and dogs. The dog is an important character in the film, as the first couple decides to abandon their dog at the end of their story, and the second one decides to adopt one instead of having children.

The film uses the dog to pin down the stories and turn them into metaphors for human interaction and the importance of language – theme present before in the director’s filmography, the most relevant example being Alphaville.

The use of 3D as well as unconventional narrative structure and unconventional elements to pin down the story for the audience to understand the metaphorical meaning of the narrative makes Goodbye to language an experimental film that is both brave and discrete, not falling into any extreme.