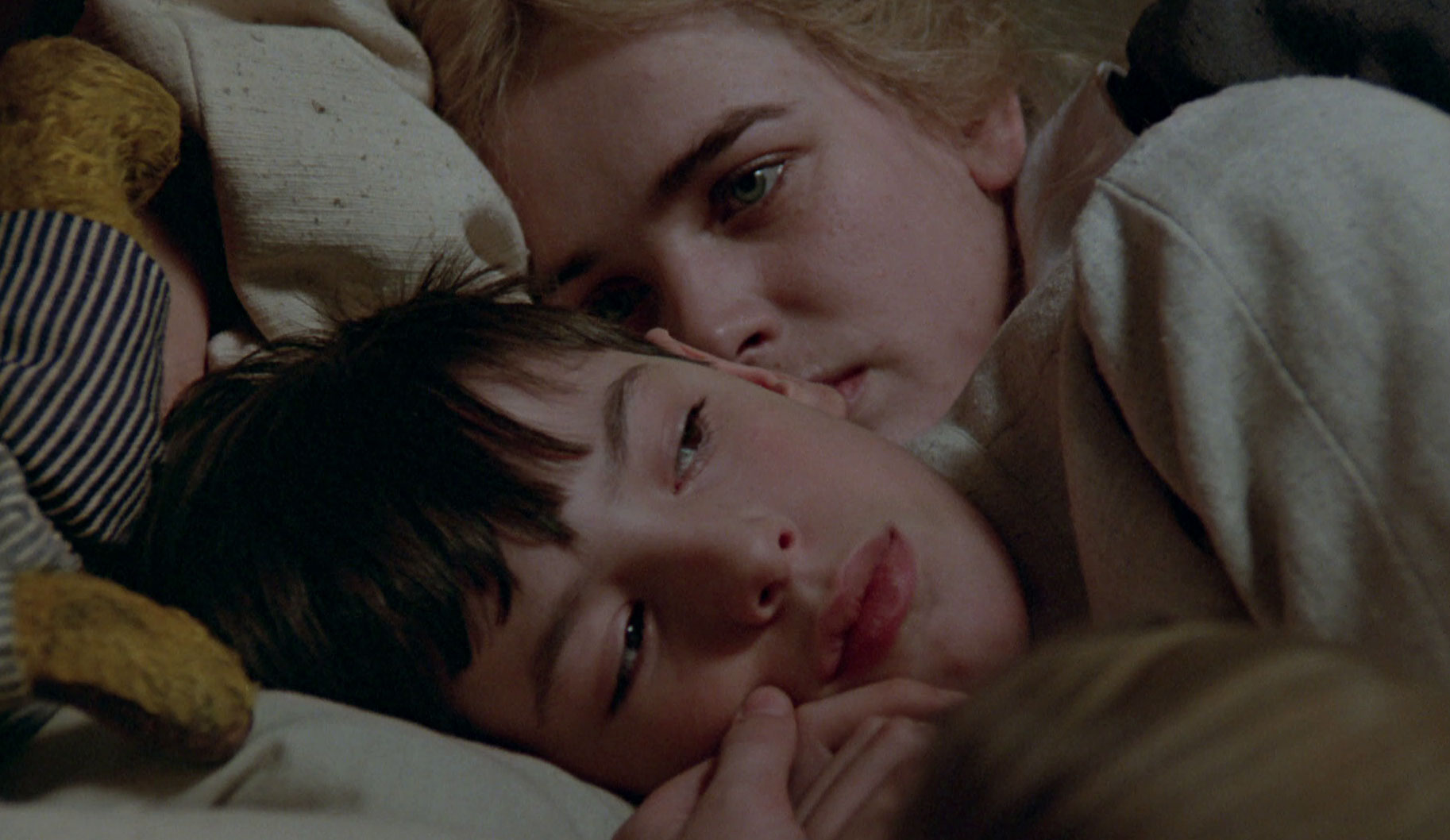

8. Fanny And Alexander (1982, Ingmar Bergman)

This film is a thinly-disguised portrait of Ingmar Bergman and his sister’s rigid, joyless and religious childhood and upbringing in the early 20th century in Sweden.

Here, the maker of “Persona” heavily dramatizes and exaggerates his and his sister’s childhood experiences in order to create a fable, or almost a fairytale, about two young siblings who meet unhappiness and hardship in a terrible way and must find the strength to get through it all.

After the death of their father, Fanny and Alexander, along with their pregnant mother, face one terrible incident after another. The worst of these incidents is the very existence of bishop Edvard, who has become their stepfather and is a cruel, hateful, abusive and miserable tyrant.

The film ends in a somewhat ambiguous manner. While making the film, Bergman had intended this to be his last feature film, so perhaps an ambiguous ending was appropriate. However, we’ll never know if Bergman overcame his inner darkness or not.

9. The Long Day Closes (1992, Terence Davies)

This is Terence Davies’ second feature length film and the one that is his most famous, recognized and admired.

Just like in Davies’ previous film, “Distant Voices, Still Lives”, “The Long Day Closes” examines life in working class Liverpool during the 1950s. It tells the story of Bud, an 11-year-old boy who spends most of his time daydreaming, watching movies at the movie theater, and trying to avoid all the bullies that are hell-bent on making his life miserable. Eventually, pop culture and art prove to be an escape, a solace and a refuge for poor young Bud.

The sole source for all the material that makes up the film is Davies’ own childhood living under strict and rigid religious beliefs. Some years later he left Liverpool. He is currently a Fellow of the British Film Institute.

10. Long Live Death (1971, Fernando Arrabal)

When Fernando Arrabal was a young boy, the Spanish Civil War had just ended and Francisco Franco was just beginning his terrorizing and near-destruction of Spain.

Arrabal’s father was suspected of being a communist. His fascist mother turned her own husband, young Fernando’s father, to the fascist authorities.

“Long Live Death” has Fando as its main character, a boy who’s obviously the alter-ego of Arrabal. The film is divided into parts that depict what may be “reality” and parts that depict surreal, brutal, terrifying, grotesque and apocalyptic episodes featuring torture, extreme violence and death, which are implied to be nightmares and fantasies of Fando. Both sides of the story are interwoven.

Perhaps after Buñuel’s “Un Chien Andalou”, this may be the greatest surrealist film ever made. It has also inspired countless musicians, filmmakers (many of them dedicated to horror), playwrights, comic book authors, performance artists, painters, and other artists.

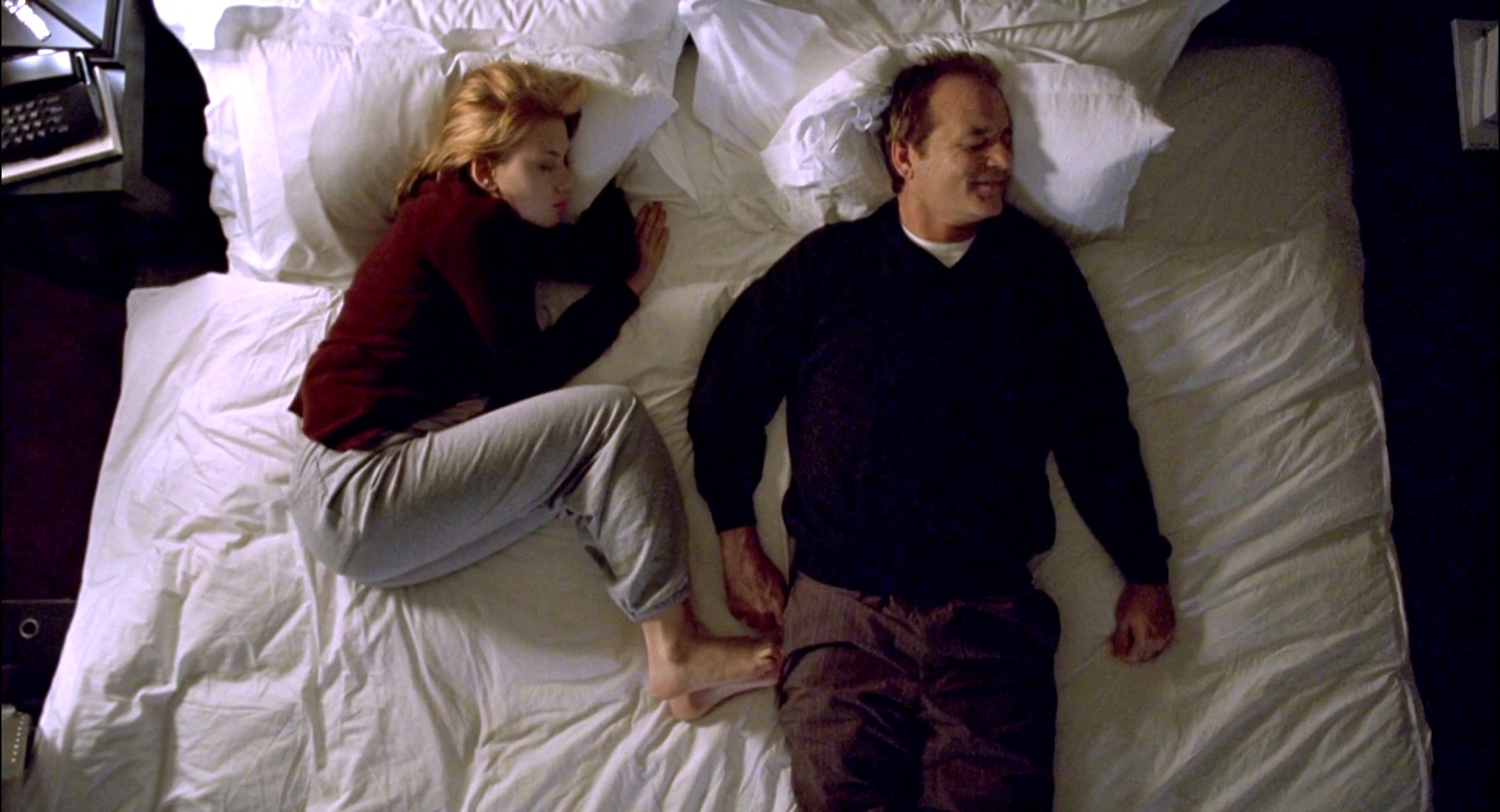

11. Lost In Translation (2003, Sofia Coppola)

“For relaxing times, make it Suntory time…”

One of the key works of art of this century, “Lost In Translation” is a truly unique film, one that transcends barriers most films can’t, and almost forces you to identify with and like (and maybe even love) its two great protagonists. It stars Bill Murray as the fading fiftysomething Hollywood star, Bob Harris, and Scarlett Johansson as gorgeous newlywed and college graduate, Charlotte, who’s already being taken for granted by her husband and failing to keeping her marriage alive.

Bob and Charlotte are both lost; they’re surrounded by people but couldn’t possibly be more alone, they are attacked by terrible bouts of insomnia and can’t get over their jet lag, they are bored, unsatisfied and filled with regrets. They’re both sad and can’t get rid of their apathy and their inability to find joy. They’re in a country on the other side of the world where they don’t understand a word of the language, and of course, they are in the very same hotel.

With that, one of the greatest, most endearing and memorable couples (not necessarily in a romantic way) in cinema history was born.

Sofia Coppola spent several periods of time in Tokyo through her 20s. The first few times she always felt lost and desperate, like she didn’t belong or shouldn’t be there. Some of those times she stayed at what she calls one of her favorite places in the world, the Park Hyatt Tokyo Hotel, where the film was shot; one of the things she likes the most about it being its “quietness”.

When Coppola wrote the screenplay for “Lost In Translation”, she was still married to her childhood friend and fellow director Spike Jonze, though it wasn’t a successful marriage (she later described it as the biggest and worst mistake of her life). However, they remained married for a short period of time, and Jonze even shot a “making-of” of the film.

It seems incredible now that one artist’s sadness, loneliness and loss could have been the sole inspiration for such a beautiful, magnificent and lovable film about two human beings connecting in the deepest way possible, but that’s one of the true beauties of art.

12. The Mirror (1975, Andrei Tarkovsky)

With “The Mirror”, Andrei Tarkovsky made his least “narrative” film. The film is a loose collection of memories, fantasies, dreams, nightmares and hallucinations experienced by the protagonist. It is based on Tarkovsky’s childhood in the Soviet Union before, during and after World War II.

A very lush and deeply textured work, the film takes advantages of sound design in very inventive and original ways. It also channels a “stream of consciousness” style of showing the “action” and experimental flourishes, like poems written by Tarkovsky’s father, Arseny, being read aloud by himself in various parts of the film.

“The Mirror” explores personal memory, trauma, the pain of loss, the tragedy of war, the experience of growing up, and mankind’s sense of mortality. The film heavily relies on visual symbolism, featuring a great number of meticulously created, arranged, framed and lightened images, often surrealistic, most of them being very memorable and others quite beautiful.

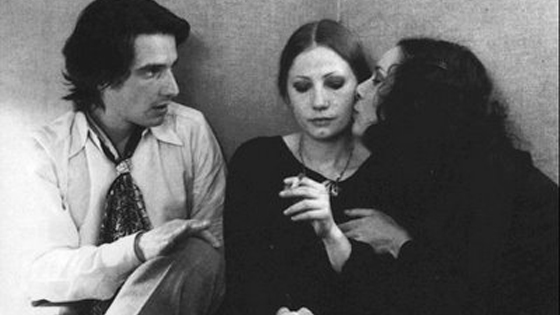

13. The Mother And The Whore (1973, Jean Eustache)

Three people in their 20s living in post-May 1968 Paris, Alexander (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud), Marie and Veronika find themselves in a love triangle.

The whole film is a set of games, displays of jealousy, narcissism, selfishness, sexual drive, indecisiveness, apathy and self-delusion. Jean Eustache cares much more about dialogue and interaction than about action, and maybe that’s why this 3-hour 19-minute film wasn’t too well received by some people when it was first released.

However, with time, it’s become a revered, untouchable classic of French cinema and an influence on many directors.

14. The Squid And The Whale (2005, Noah Baumbach)

Noah Baumbach, one of four siblings, is the son of novelist and film critic Jonathan Baumbach and film critic Georgia Brown, and was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. When Baumbach was a teenager, his parents divorced, which left a big mark on the young future filmmaker.

“The Squid And The Whale” tells the story of two boys, 16-year-old Walt and 12-year-old Frank, whose parents tell them they are separating one day in 1986.

Bernard, the father, is a once-fashionable novelist who can’t achieve success again, and Joan, the mother, has incidentally just begun writing and publishing her own works of fiction, receiving great deals of encouragement and praise.

What we have here is a very efficient, brilliantly directed and written, bitter, unmerciful, self-deprecating, cruel and sarcastic comedy that explores the worst behaviors human beings are capable of, just to hurt each other. It’s a hard, painful and very funny look at growing up, “parenting” and family.

15. The Tree Of Life (2011, Terrence Malick)

A truly difficult film to discuss, “The Tree Of Life” definitely has a life of its own, forcing you to be cautious of what you say about it, more so than any other films by the great Terrence Malick.

The film shows and explores the relations and dichotomies between life and death, loss and healing, beginning and end, resentment and forgiveness, pain and joy, innocence and harmfulness or guilt, love and contempt, atonement and despondency.

Any film that deals with all these (opposing) subjects/concepts in a truly, unapologetic serious way, especially now when serious discussion of anything is rarely encouraged or found, is always risky. It can be a very important work of art, or a self-important attempt at art. What we can definitely discuss is how the work in question is presented to us, the audience, by its author/maker.

The facts: Malick had two brothers, one of them a musician who went to Spain to study music, guitar in particular. He lost confidence, fell into what may have been a severe depression, hurt himself and passed away shortly after.

In “The Tree Of Life”, Malick’s alter-ego, Jack, has two brothers. At the beginning of the film, which occurs some years after the main narrative thread of the film, we learn that one of Jack’s brothers, R. L., has died in another country. Mrs. O’Brien receives a letter informing her of this and immediately succumbs to terrible grief. Then, we see a montage where we see R. L. playing both piano and guitar, a guitar carefully placed inside his empty bedroom, and a book about México.

In this particular case, Malick’s personal life and many elements of the film cannot be always dissociated. It would appear that most likely that Malick is presenting us “The Tree Of Life” as an attempt at healing. Healing of whom? Of Malick and anyone who sees the film and connects with it.

Author Bio: Lee Schroeder is a member of the so-called Y Generation. He likes movies, literature, music, photography and Art in general. He also likes to sleep. He doesn’t have facebook, twitter, instagram or linkedin accounts. Make of all this what you will.