Cinema can take people to the moon, re-enact gigantic battles, and take the audience to magical lands and universes. Georges Meliès, Jean Cocteau, films like “The Thief of Baghdad” and “Battleship Potemkin” are prime examples of monumental qualities of cinema, with the world building that takes place on the titanic screen. But the films of the Lumiere brothers were also about people playing cards, people in their gardens, colloquial and mundane situations.

Cinema is the place where a light can be shone on the ordinary. Siegfried Kracauer once wrote, “Life at its least controllable and most unconscious moments, a jumble of transient, forever dissolving patterns accessible only to the camera.”

1. Late Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1949)

The cinema of shomingeki, the cinema of small things, of the small events in the lives of middle class and working class Japanese people in post-war Japan, is the genre that Yasujiro Ozu brought to Western audiences and made him the “most Japanese of all Japanese directors.”

Through the serenity of Asian haiku poetry and Zen philosophy, Ozu is able to capture eternity in simple, urban, and rural scenarios characterized by quiet landscapes, static camera, and the careful composition of every shot.

Everything that happens in the film happens on a subtle emotional level, while time gently passes. Enormous emotions and topics are dealt with through small glances and tiny gestures, the way a temple stands against a serene forest, the way the rocks are disposed in a temple to create the notion of equilibrium.

Marriage, fatherhood, and happiness are some of the most important topics in the film; topics so universal and mundane that their importance is often unrecognized by a cinematic tradition that gives privilege to sensationalism and operatic, melodramatic emotions.

Of course, the cinema of small things was an already established style in the world, but Ozu brought it dignity and expanded its social and artistic potential.

2. The Headless Woman (Lucrecia Martel, 2008)

Nothing happens in this film, or maybe everything happens. The execution of this psychological drama by great Argentinian filmmaker Lucrecia Martel is bold and brilliant.

The protagonist, a middle-class woman named Vera, accidentally collides with something (or maybe somebody) while driving her car, and as she turns around while driving away in the dusty street, she sees what might be a dog, a bag full of garbage, or maybe a young person, lying dead on the ground.

The ghost of guilt starts to consume her from within, but what we witness is her normal life going forward, while a strange sense of discomfort penetrates us as the audience and her character.

Instead of turning this Dostoevskian premise into an overblown, surreal, or fast-paced psychological thriller, Martel takes a more nuanced approach.

First, she plants a seed of guilt, discomfort, and paranoia, and then keeps on filming the habitual, with careful control of imagery and pace, and naturalistic performances and warm photography, and lets the nightmare of the protagonist and the horror emerge and wander in the air like a concealed ghost.

3. The Cow (Dariush Mehrjui, 1969)

To some people, a cow is a cow, a quite graceless and unremarkable animal, and kind of boring as well. To Hassan, his cow is everything, his possession, his muse, his life, and when the cow dies and the village tells him that it escaped, he spends his life quietly waiting for it to come back, and then starts behaving like a cow, until a complete fusion happens. His madness and death take the film to tragic heights.

A small story of rural Iran became a symbol of New Iranian Cinema, as the film dealt with socio-political and philosophical topics influenced by Sufi knowledge. The film has the same innocent charm of the great Indian cinema of Ray and Ghatak, with a tale that is both realistic and full of crude poetry and an exemplary tale of morality.

The lazy calm of the daily life of the village’s inhabitants is powerfully transmitted to the audience by the austere deserted land that dominates the scenery.

By representing the soul of the nation through its most humble class of people, Mehrjui brought Iran forward in its cinematic sensibility, and led the way into a cinematic renaissance that culminated with the great films of Kiarostami, Farhadi, and others.

The fact that he did it through a deceptively simple and potentially uninteresting subject draws from the everyday life of common people added political resonance. The collective consciousness of a nation with a millenary history is contained in the history of a man and his cow.

4. The Second Game (Corneliu Porumboiu, 2014)

Football in Europe is life; it’s a popular epic, not just a sport, and the history of entire nations tend to tie itself to football games. However, the domestic pleasure that is given by watching a game with a family member, as in a consolidated ritual, is superior to all the twists and turns of history.

Corneliu Porumboiu spends this documentary film talking with his father, calmly and relaxedly, abandoning himself to the remembrance of a football game played between Dinamo Bucharest and Steaua Bucharest, a snowy game where ironically nothing really happened and where no goals were scored.

Porumboiu’s father was the referee at the game. While the audience watches the game, the dimly lit living room where Porumboiu and his father are watching the game materializes, and the comfortable atmosphere of a familiar habit penetrates the screen through the smooth tone of the two Romanians speaking, and the almost hypnotizing whiteness of the snow that keeps falling on the football players.

Football, as the most mundane and collective sport, creates a sense of immediate affection, of familiarity that recreates the magic of a single, intimate moment in time, a significant little moment of somebody’s life.

The fact that the game is also a pretty unremarkable game adds an element of humor that is typical of Romanian cinema, and also adds a sweet, nostalgic element, the idea that we can treasure unimportant, irrelevant moments if they are relevant to us, and Porumboiu explores the relationship with his father with a style that is incredibly natural and unforced. Nothing happens in the end, but everything that happens in between, which is still nothing, is what’s important, as it’s the truth of the everyday.

5. Right Now, Wrong Then (Hong Sang-soo, 2015)

To explain this film, one has to think about Jeff Mangum of the band Neutral Milk Hotel, the idea that there is a tiny white light in everything, and the idea that being alive is a delicate, tender state.

The film is very simple: a man and a woman live the same day twice, with variations between the two experiences. In the film, every element of the frame, every simple detail that enriches life, sparkles with a special kind of light, creating a blissful state of awareness of the small pleasures of life.

Every shot is very languid and softly lit, the soundtrack is nostalgic and minimal, the two actors are great, the male protagonist is relatable, awkward and self-aware, and the female protagonist is a little ball of loveliness that moves like a cat and whose gaze is timid and inquisitive.

Hong Sang-soo seems interested in parallel timelines, and themes of great postmodern literature, from authors like Calvino and Borges, typical of quantum mechanics or films like “Groundhog Day”. He treats everything without a single drop of ponderous grandeur or sensationalism, but keeps a lightness of touch that preserves the innocence of a life unexplored.

It shows the way in which we are, in a sense, temporal virgins, always moving towards a previously unexperienced state of our life, and Hong Sang-soo captures the delicate wonder that this attitude toward life brings.

6. Masculin Feminin (Jean-Luc Godard, 1966)

What did young people in Paris in the 1960s talk about? Love, literature, pop culture and politics, of course; at the end of the day, they’re the children of Marx and Coca-Cola. Jean-Luc Godard is known for a tendency towards hermetic, abrasive filmmaking, but his early work is much more free-flowing and dynamic.

In this film, he uses the large streets of Paris, and the public spaces in general, to take the viewer into the human element, and stages a series of conversations that feel improvised, in a cinema veritè style.

As a fly on the wall, we witness the conversations of intellectual but still naïve young characters who ramble about the most diverse subjects, from the Vietnam War to Bach, with an enthusiasm that captures the rhythm of young life, electric and boring at the same time. Nothing happens, but the Byronic furors of young hearts are in full display, even when they are concealed by the characters.

The result is extremely poetic, as the film seems to inhabit a timeless dimension where everything and everyone lives forever. Godard is able to capture “The Moment”, time in his present state, on the verge of being the past and transforming into the future. And then there is love, love and love.

Godard lets the viewer experience the magic of young love and young beauty in its vibrating suspension of time, through every look of Chantal Goya, through her soft voice, through the brief cameo of Brigitte Bardot with her sensual composure, through the interview with a beauty queen about social and political issues, during which she doesn’t seem to know anything substantial, but the viewer is focused on her smile, her hair falling softly on her face, her eyes, as though everything the film was trying to say was, “Who cares about the war, when she has those eyes, who cares about the politics, when she has that smile, c’est l’amour, c’est l’amour, we are alive now, in this moment, it’s just another ordinary day, and it’s love, we are love.”

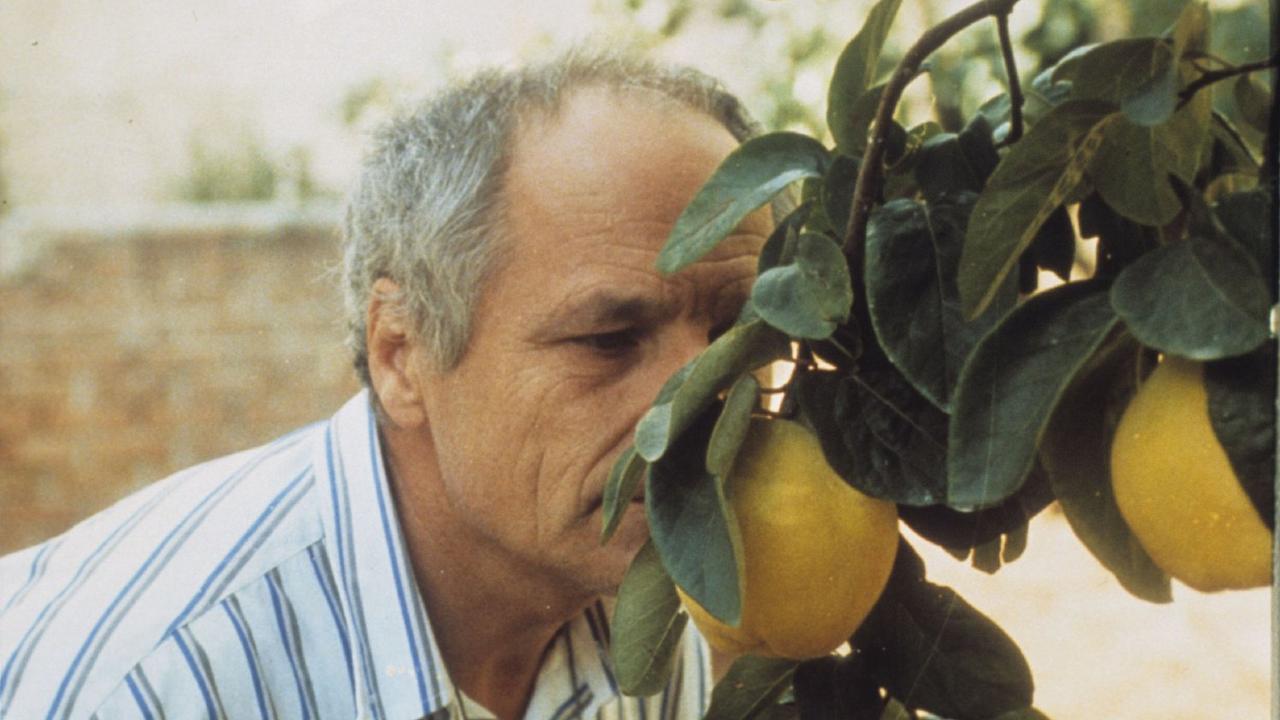

7. The Quince Tree Sun (Victor Erice, 1992)

Beauty, especially beauty that manifests itself in the most unimaginable and unexpected moments, is brief and fleeting. The role of the artist is to try and capture the passing beauty of the world, of the everyday, and preserve it for centuries.

This documentary follows a painter’s artistic process in recreating the beauty of a quince tree. The process is very long and is followed closely; the dilatation of time that happens in the film allows the viewer to feel eternity’s breath, to feel the mortality of the artist and the immortality of the art.

The wind that shakes the tree, and the sun setting, depict the passing of time in a quiet, cyclic and almost intangible way, like the passing of time in our lives, a slow and undetected decay. Death starts to insinuate itself in the film, with rotting fruit, dark skies, and the physical decline of the artist, who still does his best to celebrate life and nature in every little detail.

It is a celebration of existence, of life stripped to its bare essence, and every small detail that composes the truth of life. The film deals with grandiose themes, such as death, truth, and time, with the gentlest of touches, and a pace that celebrates both the bliss of existence and its inescapable sadness.