What some critics called “New Queer Cinema” developed almost in pair with what theorists called “Queer theory”. This theory explored every deviant category of sexuality. Queer theory proposed a wider and more complex way of reading sexuality, trying to go beyond classical LGBT labeling.

Dealing mostly with gay themes, “New Queer Cinema” explored different sexual “mismatches”, and any sexual attitude that was defiant of heteronormativity. But if the theory is quite recent, the exploration of these themes on philosophy and social studies is much older. The same goes for gender exploration in film.

This list focuses on what was called “New Queer Cinema” in the early 90s, but also expands a bit on both sides, showing some key predecessors important to understand what came next, and more recent examples on the issue. One of the most interesting points about queer cinema is how critical reception is as important as the film.

The social construction of gender is questioned in the films, and how these questions are seen by the audience tells us about the evolution of sexual notions according to context. From underground auteurs to mainstream films, queer films are still one of the most discussed issues in film theory.

1. Scorpio Rising (Kenneth Anger, 1964)

For many historians, the experimental short cuts by Kenneth Anger represent a milestone for queer cinematography. “Scorpio Rising” presents a gang of bikers preparing their clothes and partying. Without a major plot to follow, Kenneth Anger mixes different provocative elements in the film. From Nazi symbols to Christian figures, the bikers don’t seem to have a clear ideology as the film doesn’t seem to have a clear speech.

The real importance of the film lives in the way Anger configures queer aesthetics. Different masculine icons surround this gang of gay men. From Marlon Brando to James Dean, the queer aesthetic drinks from over-masculinized symbols. As masculine as these actors are, the bikers preparing their leather clothes and going out on motorcycles are just as masculine.

If queer theory talks about redefining genres or questioning its nature, masculinity in Anger’s film is put on trial. At the end, the queer community adopts the symbols of hyper-masculinity, and leather goes from this macho heterosexual clothing to the main accessory in gay clubs.

2. Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972)

For many years Judy Garland had been considered as the quintessential gay icon. Her appealing camp factor and her different biographic facts that may have had an influence in Queer culture (some say that “Somewhere Over The Rainbow” could be the inspiration for the rainbow flag), gave her the nickname “the Elvis of homosexuals”.

Immediately after the release of “Cabaret”, her daughter Liza Minnelli became a gay icon on her own merits. Like her mother, Minnelli married a man who confessed to be a homosexual in the middle of their marriage. This event coincided with the relationship that her character sustains with a man who confesses his sexuality in a moment of intimacy.

To have a confessed homosexual in a mainstream movie wasn’t a common thing at the time, especially in such a box office hit. Adding more to this mix, we have Emcee’s character. He’s a showman who introduces different parts of the show, and who presents an androgynous look. The Emcee suggests an ambiguous sexuality through his verses in the musical’s songs.

3. Pink Flamingos (John Waters, 1972)

Of all the films on the list, “Pink Flamingos” is probably the most celebrated film among queer community and theorists. It’s a film that is not regarded for its technical virtues, or because of its narrative. Instead, “Pink Flamingos” became a cult classic because of its view on disgust and its direct attack on a normative society.

Divine could be the least wanted option to star in a 70s film, but John Waters chose her to incarnate this idea of disgust. With a classic scene where Divine eats real feces, the performer did what Waters needed for the film.

Unlike the abstract figures of Kenneth Anger, or the shy Hollywood introductions of queerness of the two previous films, “Pink Flamingos” goes directly into every aspect, even defying the standard of how a good film should look. With this messy style and amateurish camera, “Pink Flamingos” stands as the most important queer film of all time.

4. Fox and His Friends (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1975)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is recognized as one of the key filmmakers in developing what we can call a queer aesthetic. For Fassbinder, there was no distinction between subject matter and a way a film looks. That’s why his films, at least those in the 70s, are a direct influence on queer filmmakers like Todd Haynes or Pedro Almodóvar.

Among his films, “Fox and his Friends” is regarded as his biggest queer statement. Fassbinder’s films were all about human relationships as an expression of power. In “Fox and his Friends” he wanted to detach completely from a common gay strategy that consisted of showing a homosexual relationship as healthy and harmonic to produce an easy acceptance of their love to audiences.

For Fassbinder, this was a trick not related at all to reality. Gay love was as vised as heterosexual, and it was poisoned by power struggle. In “Fox and his Friends”, love is buyable, and Franz’s character is incapable to adapt to high society and their rules, so his lover doesn’t find any reason to stay with him.

5. The Times of Harvey Milk (Rob Epstein, 1984)

Most of the films on this list deal with the relationship between the queer community and normative society. Some films can have a proud profile on it, and others present instead a plea for acceptance. Both points of view never won more power in the United States until the efforts of Harvey Milk, the first openly homosexual supervisor elected to public office. The political campaign of Harvey Milk was centered on gay rights, but it also included any kind of minority in San Francisco.

Milk’s campaign is remembered as an epic victory. Milk won his place very slowly, winning the support of different non-gay sectors in order to win the election. The film was completed after his assassination under former supervisor Dan White’s hands. The film presents the facts in a classical biographic documentary style, but its importance shows how much the life of Harvey Milk changed the face of its country toward queer community forever.

6. The Garden (Derek Jarman, 1990)

The end of Derek Jarman’s filmography can be seen as a conclusion of modern gay culture. After his punk films, his queer interpretation of New Wave, and especially his revisited historical figures, the biggest angst came in his latest films. After knowing about his AIDS diagnosis and his struggle with some of its physical consequences, the content and especially the form of his films became even more radical.

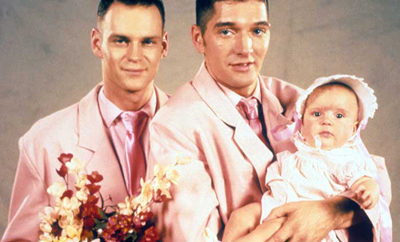

The most famous one is his last film, “Blue”, consisting of no image except a blue screen with sounds. But before that, we find “The Garden”. This film was made as a direct response to Clause 28 in England, an amendment proclaiming that “promoting homosexuality” in art was forbidden.

After this law, Jarman filled the film with a homoerotic imaginary, made direct references to the clause, and released this abstract collage of scenes about what it means to be a declared homosexual in this context. Jarman was surely a brave director, and his disease can be seen as the official start of “New Queer Cinema”