7. Cani arrabbiati (Rabid Dogs) – Italy – Mario Bava – 1974

‘Rabid Dogs’ spent 25 years on a road to nowhere. The filming was 99% completed in 1974 when the production had to be abandoned due to the producer entering bankruptcy and all footage from the film being impounded.

Mario Bava would pass away in 1980 never able to personally oversee a release of the film. It would take until the mid-1990s until it was realised that a first cut of the film on 35mm actually existed, and following several years of legal wrangling, the film finally received a release via DVD in 1998.

Just to confuse matters further – there are now several cuts of the film available, with an alternative version prepared by Bava’s son Lamberto entitled ‘Kidnapped’ also being available. Though most right thinking people will tell you that the ‘Rabid Dogs’ version is the superior cut.

As for the actual resulting film – whilst Mario Bava will always be best remembered for the run of stunning gothic horror pictures he directed during the 1960s, come the 1970s a more vicious cynicism began to inflict Bava’s work, notably 1971’s searing proto-slasher movie ‘A Bay of Blood’.

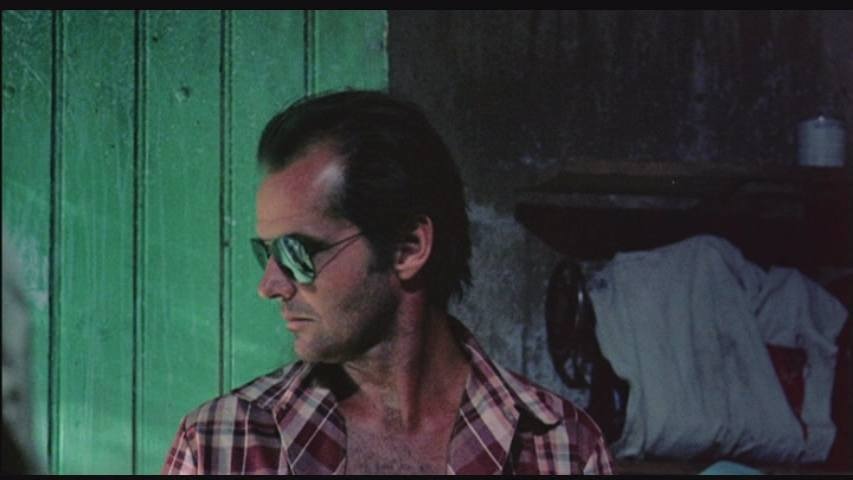

By the time he was filming ‘Rabid Dogs’ this cynicism had disintegrated into pure black nihilism with this tale of three bank robbers who upon conclusion of a heist, take a female hostage and proceed to commandeer a car being driving by an initially meek man trying to take his sick son to hospital.

The film was being made during the peak of the Poliziotteschi genre, which reflected the fashion for violent vigilante cinema at the time, but ‘Rabid Dogs’ is almost an ‘anti-Poliziotteschi’ in its exclusive focus on criminals rather than the renegade cops chasing them.

Shorn of the psychedelic delirium that defined Bava’s earlier works, this is a brutally real, sweaty and claustrophobic movie. Our protagonists play out competitive mind games and psyches begin to crumble. It’s essentially the great European road movie that Sam Peckinpah never made.

8. Les valseuses (Going Places) – France – Bertrand Blier – 1974

Bertrand Blier’s iconoclastic tendencies were in 5th gear for this early career road movie. This purposefully and gleefully offensive flick is a middle finger in the eye to mainstream morality in a way that would later be emulated by American enfant terribles such as Harmony Korine and Gregg Araki, plus France’s very own Gasper Noe.

The film follows a pair of young aimless louts Jean-Claude (a youthful Gerard Depardieu well before his Falstaff esq days) and Pierrot (Patrick Dewaere).

The film drifts episodically with our protagonists stealing and fucking their way around France. Blier treads a fine line – the film’s immaturity (the literal meaning of the original French title being a slang term for testicles) always just managing to stay the right side of yawnsome ‘Confessions of’ style sex-comedy farce.

Blier catches the audience somewhat off-guard midway into the movie when he introduces the character of Jeanne (Jeanne Moreau) – her performance and character arc taking the film into darker territory, the conclusion of which slightly numbs the viewer – casting a shadow over the film’s subsequent return to its earlier semi-transgressive joviality. Though in all probability, these confusing contrasts in tone are likely yet another joke played upon the audience.

9. Professione: reporter (The Passenger) – Italy – Michelangelo Antonioni – 1975

The precursor to Wim Wenders (see below) as the master of existential European wanderlust – Antonioni’s mist-strewn evocation of the Italian Po Delta in ‘Il Grido’ had been an early entry into the European art-house road movie canon. His surrealistic descent into the mindset of an embittered American counterculture, with the unfairly maligned film maudit ‘Zabriskie Point’ had also embraced the genre.

‘The Passenger’ follows David Locke (Jack Nicholson in the most restrained performance of his career) a journalist working on the edge of the Sahara Desert who upon finding out that another resident of his hotel has died suddenly, decides to use the opportunity to shed the skin of his dissatisfying existence and swap identities with the dead man.

Little known to Locke, the dead man just happened to be an international illegal arms dealer. Locke returns to Europe and initially embraces the liberation his new found identity allows him, but soon finds himself pursued by the dead man’s many enemies in a chase through Spain.

On paper, a taut thriller, in Antonioni’s hands – another study of the meaning of identity, as Locke sees his sense of such gradually fragment and disappear as the picture heads towards one of cinemas all time great closing shots.

10. Im Lauf der Zeit (Kings of the Road) – Germany – Wim Wenders – 1976

If asked to name one European director inextricably linked with road movie cinema, most would choose Germany’s Wim Wenders. His early career was tied into a wandering spirit as far back as early pictures such as ‘Summer in the City’ and ‘The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty Kick’. In fact his own production company is even actually named ‘Road Movies Filmproduktion’.

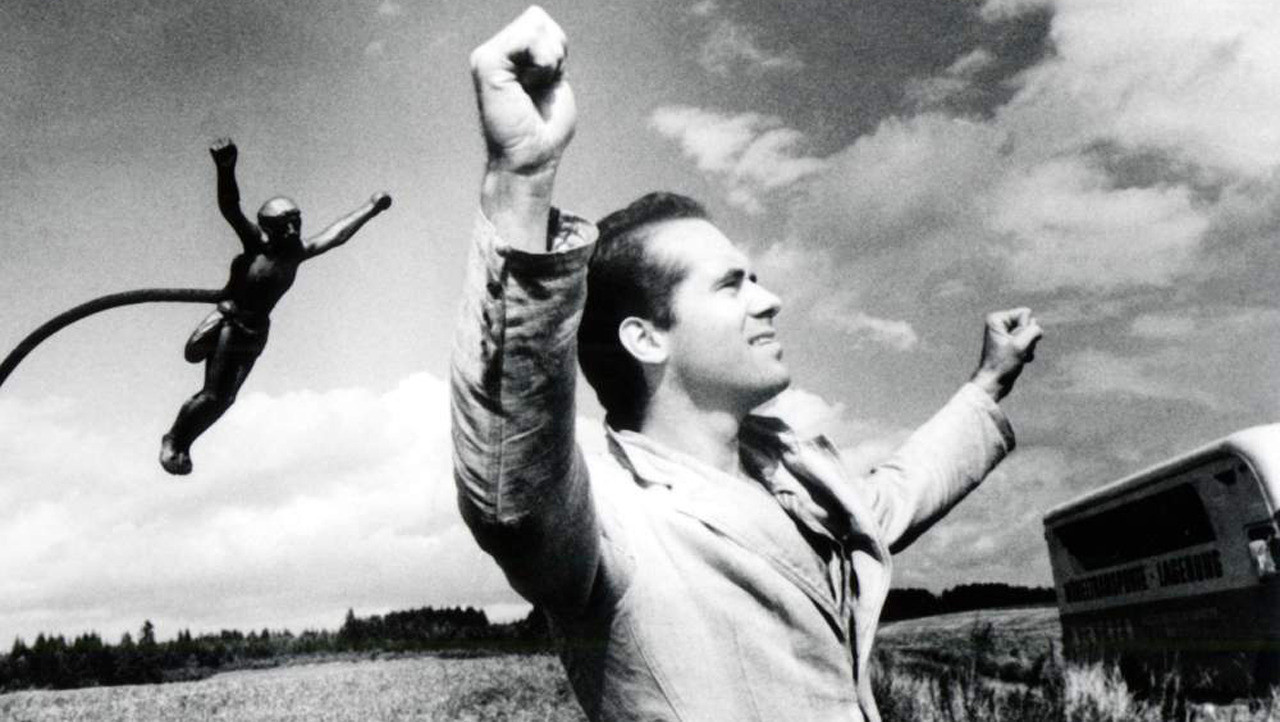

He really hit his stride critically with a mid 70s trilogy of road movies – opening with the fantastic ‘Alice in the Cities’, next would follow ‘Wrong Move’ before concluding with the epic 3 hour magnum opus ‘Kings of the Road’.

As stated earlier, in Europe you are never far from a new border, ‘Kings of the Road’ is a film truly concerned with borders and sense of identity in relation to said borders. Rudiger Vogler (who also starred in the previous two films in the trilogy) plays Wilhelm who travels along the east/west border of Germany travelling from town to town servicing cinema projectors.

As per buddy movie convention, his mundane existence is given a shake with the introduction of the suicidal Laertes (Hans Christian Blech) who subsequently joins him in his truck as he travels from town to town.

This being a Wim Wenders film, their introduction serves to be the only concession to buddy movie tropes. The film instead becomes the most fully realised of Wenders’ attempts to mould the widescreen world of American road movies together with the German literary tradition of the existential Bildungsroman.

The characters travel through a barely populated border hinterland of towns haunted by recent German history. Coupled together with an amazing melancholic soundtrack, this proves to be a vital landmark in the European road movie canon.

11. Radio On – UK – Chris Petit – 1979

You could simplify Chris Petit’s debut picture down to the high concept pitch of “Get Carter as envisaged by an early 70’s Wim Wenders” but that would sell this road movie for the post-punk generation far too short.

The film follows Robert (David Beames), a late night factory DJ in London, who after we have followed him listlessly attending to his daily routine for a while, is informed that his brother has died mysteriously in Bristol. Robert therefore decides to take a road trip to Bristol to deal with any matters that may need clearing up.

Rather than the embrace of the road as a site of freedom and mobility, this is a place where the road will soon come to an end, the endless horizons replaced with concrete wastelands (echoes of J.G. Ballard are numerous and clearly intentional) and utilitarian motorways – this is On the Road as written by Orwell instead of Kerouac.

Even when our protagonist reaches the countryside he faces an unwelcoming hibernal bleakness still stuck sometime in the mid 1950’s.

A society that struggles to communicate, preferring to hide behind the steering wheel, becomes the films central metaphor. The opening scenes present a dystopian London crumbling under the weight of government mismanagement. Our protagonist attending to his job as a factory DJ, alone in his booth playing music to uninterested factory workers, non-descript in their identical white overalls. It’s in image of alienation as potent as anything seen in Antonioni’s work.

The central narrative of the dead brother in the end proves to be somewhat of an enigmatic macguffin, an incidental event to allow the narrative to propel forwards. The narrative appears to matter little if at all to Petit, who instead concentrates the film’s energies on a veneration of the image and the wonderful soundtrack.

The mise-en-scene of a pre-Thatcherite Britain in post industrial decline is backed by a Teutonic futurist soundtrack of Kraftwerk and Berlin era Bowie. Even the ode to youthful rebellion that is “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” is presented in a disjointed and fractured way by virtue of its Devo cover version, draining away any hint of youthful abandonment.

The greatest of British takes on the road movie, and sure to find favour with fans of Antonioni, Wenders, post-punk, brutalism and Ballard.

12. Ко то тамо пева (Who’s That Singing Over There) – Serbia – Slobodan Šijan – 1980

Along with the works of Emir Kusturica and Dusan Makavejev, Serbia’s finest cinematic export is this blackly comic road movie following a bus and its eccentric group of passengers en route to Belgrade on the day before the city was bombed by Nazi’s during March 1941.

If we have two central protagonists with which to connect, it’s two young gypsy boys, who when not being targeted for bigoted abuse by fellow passengers, provide the film’s Greek chorus in a series of musical interludes with infectious accordion and Jews harp melodies.

The film chooses to present the madness of war as a dreamlike trip where irrationality becomes the norm – not unlike the previous year’s boat trip of ‘Apocalypse Now’ – you don’t have to be insane to survive the war, but it helps…

The film echoes Bunuel in its mockery of the state. All officials we come across taking their dedication to nonsense bureaucracy to extremes. Particularly the bus conductor who insists upon frequent re-checks of everyone’s ticket stubs.

It can be a cruel film, but it’s definitely a humanist film and measures its balance of pathos and humour perfectly. This is a film seriously deserving of wider recognition.

13. The Hit – UK – Stephen Frears – 1984

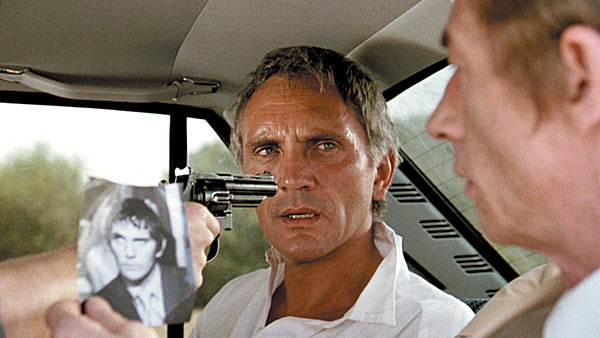

Stephen Frears’ gangster road movie echoes the elliptical metaphysical world seen in earlier art-house gangster outings such as John Boorman’s wild neo-noir ‘Point Blank’ and Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg’s countercultural headtrip ‘Performance’.

The film begins with gangster Willie Parker (Terence Stamp) turning supergrass against his fellow London underworld associates. We then fast forward ten years, where Willie, now living with a new identity in Spain, is tracked down and to be taken to Paris for assassination by two hitmen – the menacing Braddock (John Hurt) and his young accomplice Myron (a young Tim Roth, fresh from his star making turn in Alan Clarke’s ‘Made in Britain’).

The ride to Paris is due to be a long one and within the confined space of a saloon our characters begin to toy with each other’s psyches, variously bluffing attitudes and playing poker faced games with each other, the atmosphere threatens to bloodily boil over at any moment.

Like Antonioni’s ‘The Passenger’, the picture postcard vistas of the Iberian Peninsula are anything but in this dark bitterly comic thriller.