14. Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) – France – Agnes Varda – 1985

Arguably the greatest film in Agnes Varda’s long and celebrated career, Vagabond is a tough portrait of self-imposed alienation, taking the youthful idealism of dropping out of society and stripping it of any of the sentiment and wistful romantic sense of liberation seen in films such as Sean Penn’s ‘Into the Wild’.

We discover at the outset of the film that Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) has died, frozen in a ditch in a wintery French hinterland. The film then flashes back to the last few weeks of her life, building back towards her fateful final moments with a documentary like detachment. Mona is an enigma, refusing the often condescending offers of help that she receives whilst hitchhiking through the French countryside. She never betrays any particular emotion or context that justifies her transient lifestyle.

This ambiguity works in the film’s favour, leaving us with a plaintive work that leaves an imprint on the mind long after viewing.

15. Pidä huivista kiinni, Tatjana (Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana) – Finland – Aki Kaurismäki – 1994

Aki Kaurismäki’s most well known film internationally is a road movie, not this one, but rather 1989’s ‘Leningrad Cowboys Go America’ a musical roadtrip transplanting Kaurismäki’s dry as Death Valley humour into the tradition of disastrous screwball American road trips.

Five years later back in his native Finland he released this, one of the most stripped back and deadpan comedies from a director famed for stripped back and deadpan comedies.

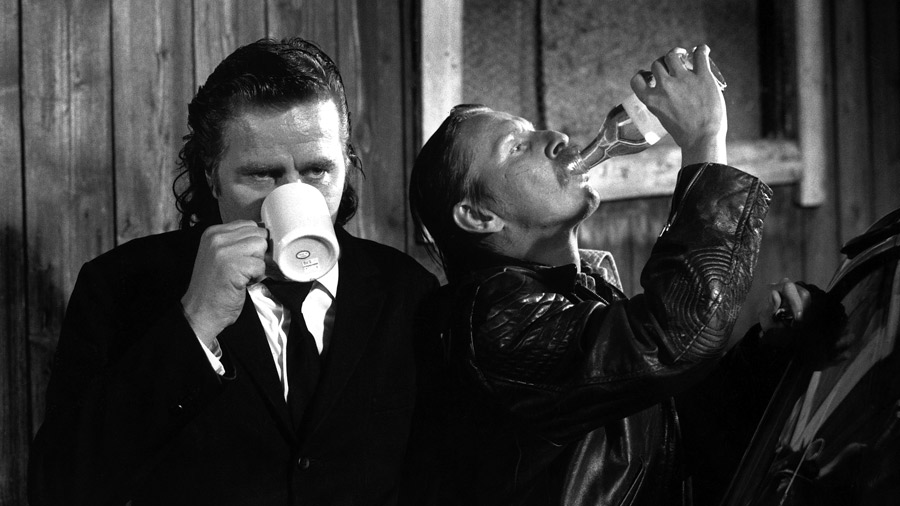

We follow Valto (Mato Valtonen) and Reino (Kaurismäki’s most frequent collaborator, the masterful Matti Pellonpää). Valto is a coffee addict, Reino prefers to neck vodka, both are running short, this necessitates a quest for more.

Once both are satisfied they hit the road on a caffeine and booze laden road trip that sees them pick up an Estonian woman, the titular Tatjana (Kaurismäki’s muse Kati Outinen) and Russian Klavdia (Kirsi Tykkyläinen). A very tentative romance develops amongst the foursome, hampered by language barriers, shyness and aloof barrier building being used as an emotional defence mechanism.

Fans of Kaurismäki’s low-key brand of cinema will be in raptures with this charming (charm in the sense that only he can pull off) little film, with another great late performance from Pellonpää in particular, who tragically would pass away only a year after the release of this film.

16. Á köldum klaka (Cold Fever) – Iceland – Friðrik Þór Friðriksson – 1995

As close as European cinema has ever got to the deadpan work of the United States’ favourite hipster auteur Jim Jarmusch – ‘Cold Fever’ is a minor gem well worthy of wider attention.

Masatoshi Nagase (most well known in the west for his appearance in Jarmusch’s ‘Mystery Train’) plays Hirata, a yuppie businessman planning a holiday to Hawaii. Before jetting off he is accosted by his grandfather (a cameo from art-gangster-punk flick legend Seijun Suzuki) who insists that Hirata visit Iceland where his parents had drowned in an accident seven years previously. As per Japanese custom, he must perform a ceremony at the sight of their deaths so that their souls may rest.

What follows is a trip through an otherworldly wintery Iceland. Dreamy visuals support a comic travelogue in which Hirata comes across several quirky characters on his odyssey; be they local booze hounds or tourists on a robbery spree. The film works towards a well earned quietly emotional ending. Only currently available through an out of print UK DVD, ‘Cold Fever’ is a film that really deserves more.

17. Возвращение (The Return) – Russia – Andrey Zvyagintsev – 2003

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s debut feature The Return employs a muted colour palate, where images are drained of vibrancy to the point where every colour seems to be a variant on blue or grey. Emptied provincial towns, looking shut down in a perpetual loop of dull bank holidays, decaying warehouses creating a dystopian atmosphere echoing Tarkovsky and ‘Stalker’ early in the film, a further echo being that both films are framed within a foreboding journey and discovery template.

The narrative of The Return is stripped to a bare bones approach and is all the better for it. The film concerns two brothers Ivan (Ivan Dobronravov) a mummy’s boy on the cusp of adolescence and Andrey (Vladimir Garin) a few years older and determined to impress his peers. One summer day they return home to be informed that their father (Konstantin Lavronenko) unseen since they were toddlers, has returned and is intending to take them on a fishing trip to make up for lost time.

Rather than a heartfelt family reunion, the father is met with immediate suspicion, especially by Ivan, who attempts to test his father’s patience from the off and questions his motives for returning. Not that his suspicions are completely unfounded as the father acts cold and brusque, toying emotionally with the brothers and lambasting them for perceived weaknesses in their characters.

The first half of the film takes place largely in the confines of the fathers 1980s Gaz Volga (imagine a Volvo made with Iron Curtain spit and gristle cost cutting economy rather than Swedish proficiency), and concentrates on the less ecstatic aspects of family road trips, the boredom of confinement, the monotony of unvarying landscapes and the resulting shortened tempers of those caught up in this scenario.

As the film progresses, a sense of menace and dread begins to take hold as we are invited to share in the brothers’ suspicion of the increasingly authoritarian actions of their father. By the time the trio arrive at their fishing destination on a secluded mid-lake island, this ominous atmosphere builds towards an almost inevitably crushing conclusion.

18. Aaltra – Belgium –Benoît Delépine & Gustave de Kervern – 2004

As blackly comic as it comes – the country that gave the world ‘Man Bites Dog’ does it again with this tale of two neighbours whose mutual hatred leads to a fight in which both of them end up being crippled by a piece of poorly constructed farm machinery.

Once released from hospital our now permanently wheelchair bound pair agree to drop their feud long enough to join forces and take a road trip to Finland to sue the company deemed responsible for their plight (the titular farming machinery firm Aaltra).

Predictably a smooth course is not sailed as our pair continue to bicker, offending every good Samaritan who attempts to help them and committing several low level crimes in order to complete their journey.

Aaltra is well worth checking out, even if only for the closing punch line (featuring a cameo role for Aki Kaurismäki), a scene which is worth the price of entry on its own.

19. Feux rouges (Red Lights) – France – Cédric Kahn – 2004

‘Red Lights’ arrived bang in the middle of a renaissance for French thrillers – with a series of films betraying a post-millennial tension, often zooming in on bleak and violent studies of human behaviour. Whilst ‘Red Lights’ does not venture into the extremities visited by say, the wild Thelma and Louise on acid trip of ‘Baise Moi’ – it still provides a nihilistic punch.

Here we see yet another marriage breaking down behind the confines of the steering wheel. We follow Antoine (Jean-Pierre Darroussin) and Helene (Carole Bouquet) as they leave Paris and travel south to pick up their children from summer camp.

The situation is not helped by Antoine’s secret alcoholism, with him using every possible opportunity to secretly top up on booze. The situation eventually comes to a head at a service station, with Helene disappearing; having declared that she will travel alone by train.

Hints have been dropped throughout the film to this point through shrewd diegetic use of the car stereo that a serial killer has escaped from prison. Throwing this into the mix, with Antoine’s ever increasing alcoholic mental disintegration as the night goes on – the film turns into a road-trip hybrid of Billy Wilder’s ‘The Lost Weekend’ and George Sluizer’s ‘The Vanishing’ (the brilliant Dutch original rather than the blunted American remake).

‘Red Lights’ is a taut, intense, somewhat disturbing thriller with a classic French dollop of bating the public facade of the bourgeoisie and is well worth hunting out.

20. Locke – UK – Steven Knight – 2013

We close with the recent opinion dividing British film ‘Locke’, a character study following one man’s carefully constructed sense of identity crumbling over a single night, with a daring formal concept of having the whole episode play out behind the wheel a BMW X5 as we journey down a night-time motorway.

Our man Locke (a reference to Antonioni’s ‘The Passenger’ and its questions of identity?) is a construction manager on the eve of the biggest job of his career. Despite this he is driving away from the Birmingham location of the job at high speed down the M1 to London.

Through a series of phone calls it becomes evident that a brief affair nine months earlier has resulted in a pregnancy. Left with a choice between facing up to his responsibility as a father and career ruin, his journey becomes a dark night of the soul as he fights against the horrific realisation that he is risking turning into his own neglectful cruel father.

As is often the case with Tom Hardy, his thespian approach divides opinion. In this case he chooses to employ a thick Welsh accent – which works for some, but equally turned off others. But this is an original slice of brisk and intense cinema which shows that whilst the European road movie might not give us the same vistas and wanderlust of elsewhere in the world, it does continue provide for a vital and creative template for some of Europe’s most interesting directors.

Authur Bio: Lee Teasdale is from the Lake District in England but is currently paying his dues down in London. A film graduate in a former life, he is currently working on books about 1970’s road movies and violence in the road movie, but alas at the speed of continental drift, so it may be while. He occasionally spouts inane crap at https://twitter.com/RadioFreeLee. He loves roads and cars and movies.