A quintessential American music icon, Bruce Springsteen is associated with a great many aspects of American culture – support for veterans, economic populism, the freedom of the road, romanticism leavened by fatalism. In addition to these characteristics that define his music, Springsteen’s lyrics rely heavily on cinematic techniques.

His songs are populated with characters in narrative situations, as many of the songs become vignettes that illustrate the trials and tribulations of those he finds dramatically interesting. Most famously, his 1975 album Born To Run is designed so that each of the eight tracks is meant to be taking place on the same day and night in New York City and New Jersey, lending narrative unity to the individual songs. The result, not unlike a film, is that one can imagine these characters’ intersecting lives depicted in montage, with edits aligning their hopes, dreams, and failures with one another.

The complex relationship between Springsteen and cinema has often been symbiotic. As a songwriter, Springsteen wears his own cinematic influences on his sleeve – his songs are frequently about outlaw characters, living on the margins of things, not unlike those who populate classic film noir. He often makes references to movies and the power of film on his characters in his lyrics, and uses cinematic genre tropes (crime films, most frequently) to close the grip tighter on those people whose lives he chronicles.

Beyond this direct inspiration, however, some films have used his music to inspire them. Though not included in the list below, Norman Jewison’s film In Country (1989) uses “I’m On Fire” from Born in The USA (1984) to great effect, weaving it throughout the narrative to comment on his main character’s loss of her father in Vietnam.

Still other films are analogous to Springsteen’s aesthetic, where they engage directly with it or not. Simply put, the rich cinematic tapestry found in Springsteen’s music would be enhanced by viewing the following films, and those fans of the films might find something to like in the music, though they may not intersect directly.

At a 2008 rally campaigning for then-Senator Obama, Springsteen said this about his own mission as an artist: “I’ve spent most of my creative life measuring the distance between that American promise and American reality.” The following films cover that same ground, roughly following the chronology of his albums.

1. Thunder Road (1958, Dir. Arthur Ripley)

The story goes that Bruce Springsteen, without having seen this film, saw the title on a poster and swiped it for the first track, “Thunder Road,” from 1975’s Born to Run. Even if it’s true (Springsteen says it is, and that he has seen the film since that time), without any direct knowledge of the film’s story and themes, it’s tailor made for his music.

The story, developed by lead actor Robert Mitchum, is about a young Korean War veteran who turns to running illegal moonshine throughout the south, gunning his engine along highways at night with contraband in his trunk.

One of the earliest films to make extended use of car chases to drive action, Thunder Road is a movie in many ways about the romanticism of the highway and the possibility that the road can bring.

Mitchum’s Luke Doolin is the type of rugged anti-hero that populates many Springsteen songs, and it’s not hard to imagine him as the actor referenced in “Backstreets” (also from Born To Run), when that song’s narrator recalls “all the movies, Terry, we’d go see / Trying to learn how to walk like the heroes we thought we had to be.” The film is also rife with the same undercurrent of fatalism found in much of Springsteen, as Luke begins to run out of road as the film hurtles towards its conclusion.

2. Rebel Without a Cause (1955, Dir. Nicholas Ray)

Cars are essential to the kids in Nicholas Ray’s classic melodrama about alienated youth. One of the film’s most famous set pieces is the ‘chickee run’ between James Dean’s Jim Stark and his rival Buzz, where each races a car towards a cliff in an effort to prove who is the bravest. The scene roars to life with the engines, and Ray films the cars with the same romanticized eye that he uses to shoot his young stars (Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo).

The film’s general story, about Jim’s rebellion against his middle class parents, seems dictated by the same dramatic excitement of breaking away that runs through many early Springsteen classics like “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” and the obscure “Zero and Blind Terry,” but Rebel Without A Cause also ends in tragedy, like Springsteen’s “Jungleland.” The characters in the film and “Jungleland” are bigger than life, over the top, and inevitably gunning for the tragic end that represents the death of youth but the possibility of rebirth in adulthood.

3. The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984, Dir. Stuart Rosenberg)

Rosenberg’s film, based on the novel of the same name by Vincent Patrick, also features bigger than life characters – they’re colorful rogues, charismatic hustlers, and charming gangsters, each of whom seems uniquely fitted to New York City, the setting of so much of Springsteen’s early music. The humorous, playful relationship between Charlie (Mickey Rourke) and his no-good cousin Paulie (Eric Roberts) has echoes of Springsteen’s groove on “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out,” an origin myth about the founding of the E Street Band.

While the film never reaches a true feeling of dangerous tension, it contains some grisly images (Paulie’s punishment for robbing a gangster is the loss of a thumb, for example) that are in keeping with the ominous “Meeting Across the River” from Born to Run.

In that song, the narrator describes a situation to a friend of his, Eddie, about a score that’s sure to get him out of trouble. It better, too, because, he tells Eddie, “word’s been passed this is our last chance.” The ‘one last score’ ethos of the song evokes an entire genre (film noir) and the darker elements of The Pope of Greenwich Village, even though those consequences don’t fall on Charlie and Paulie the way we might expect them to.

4. Five Easy Pieces (1970, Dir. Bob Rafelson)

The New Hollywood of the 1970s opened the door for protagonists who were often less than likeable, and who made choices that were strange and even occasionally perplexing. Jack Nicholson’s iconic performance in Rafelson’s film as an oil worker running away from his family (and a past as a piano prodigy) is definitely of a piece with many Springsteen songs, which track the alienation of working class men who yearn for something beyond the work they do.

After the film’s early scenes in the oil fields, it turns into a road movie as Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea heads to the Pacific Northwest to visit his dying father, with his girlfriend Rayette (Karen Black) along for the ride. After stashing Rayette in a motel, Bobby heads home, and has a brief affair with Catherine (Susan Anspach), his brother’s fiancée. Though opaquely presented, in keeping with the style of the films of the Hollywood Renaissance, Bobby appears to be search for some kind of connection.

This film, like the Springsteen songs “Hungry Heart” and “Stolen Car,” are about the erosion of those relationships, or the missed connections that keep people apart. The film ends, as Bobby and Rayette head south, with Bobby stopping at a gas station.

As Rayette heads inside to buy cigarettes, Bobby hops aboard a lumber truck, leaving his car, his belongings, and Rayette by the side of the road. Though it predates the song by ten years, Five Easy Pieces creates in images what “Stolen Car” does as it concludes: “But I ride by night and I travel in fear / That in this darkness I will disappear.”

5. Homeboy (1988, Dir. Michael Seresin)

Springsteen’s 2005 song “The Hitter,” from the album Devils & Dust, tells the first person story of a boxer who’s been through his share of fights, and captures the desperation of a man at the end of his road. Homeboy, written by (under a pseudonym) and starring Mickey Rourke, covers the same ground, but does so in a way that makes the film especially resonant with Springsteen’s music – it’s setting is the beachside New Jersey town of Asbury Park, a place that Springsteen has referred to as his adopted hometown, and where the E Street Band first began playing in seaside bars.

Much of the film is set at night, and often in the rain (an image that recurs in “The Hitter”), and makes use of the boardwalk locations that appear in Springsteen’s “Sandy (4th of July, Asbury Park)” and a number of his other early tracks. The carnival run by Ruby (Debra Feuer), Johnny Walker’s (Rourke) love interest in the film, also makes up a key set of the film’s visual tropes.

The crime that is pervasive throughout the film, which is populated with gangsters, crooks, and unethical cops, also chronicles some of the same territory that Springsteen would lament in 2002’s “My City of Ruins,” written about Asbury Park’s decline.

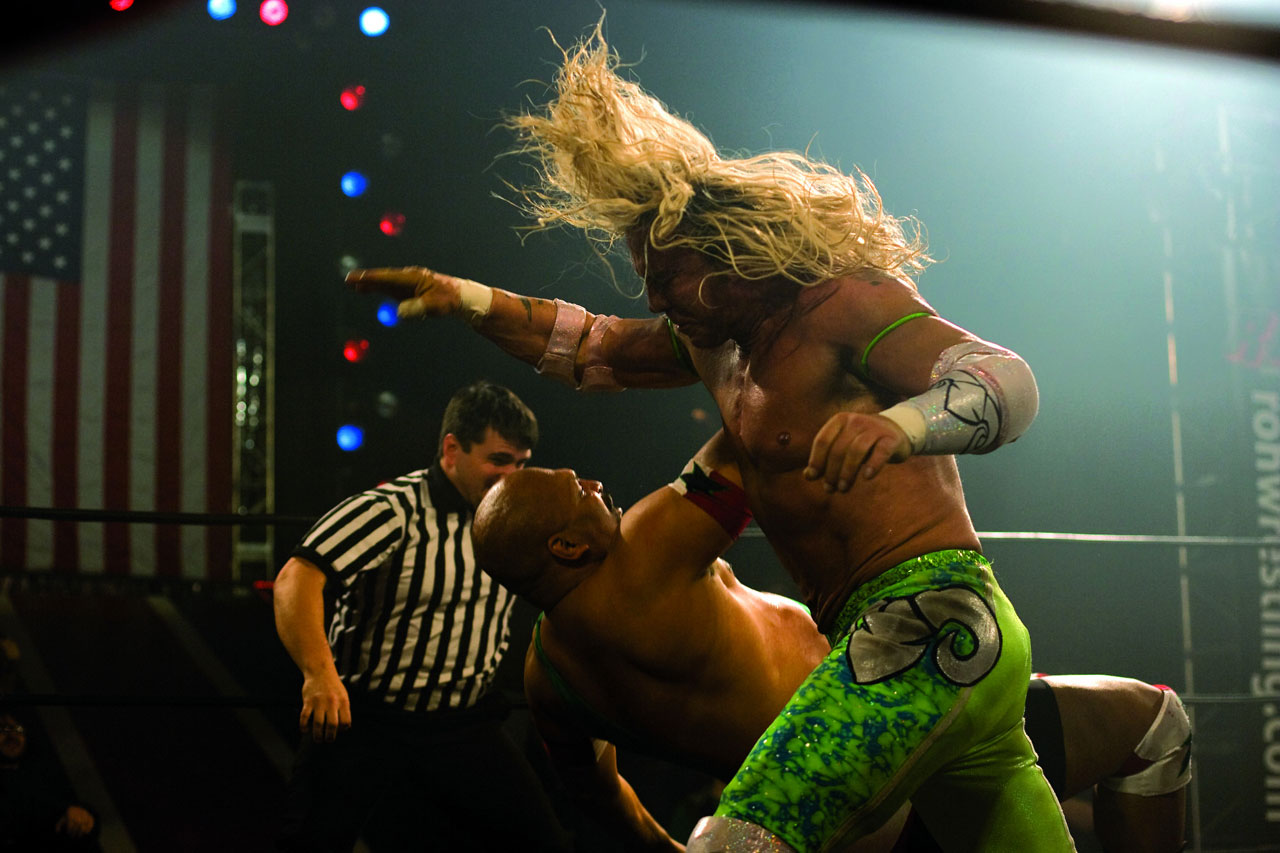

6. The Wrestler (2008, Dir. Darren Aronofsky)

Springsteen composed a song for this film, called “The Wrestler,” which accompanies the closing credits, making the connection between his music and cinema explicitly clear. There’s also the New Jersey setting, which makes this film something of a spiritual sequel to Homeboy, as it retraces some of that film’s steps – its climactic wrestling match is held at the Convention Center in Asbury Park, the setting of Homeboy and Springsteen’s adopted hometown, and Mickey Rourke again fills the role of a broken man who seems right at home in a Springsteen song.

Beyond these connections, there is also the sense that Randy “The Ram” Robinson (Rourke) is trapped by his profession. A brief interlude features Robinson (forced into retirement due to a heart condition) trying his hand behind a meat counter at a supermarket, but it ends badly, with Randy giving himself over to the same theatricality he would use in the ring.

In addition, Randy, after deciding to return to the ring for one last comeback match, ends the film by confronting the darkness he faces head on, and choosing to “keep pushin’ ‘til it’s understood,” as the lyrics to Springsteen’s “Badlands” suggest. Randy refuses to bow down, compromise, or sacrifice himself. He, like many of Springsteen’s characters, is what he is, and commits fully to remaining true to his identity, despite the overwhelming despair that confronts him.