11. Little Miss Sunshine (2006)

This is a film so distraught from hope that only the ideas of Bertrand Russell could revolve this uneven pack of strangers, who find each other in the perfect moment of their lives.

The key here is the heart that drives the disagreement of each one of its picturesque characters. The silence that resonates heavily from Dwayne is what Frank chooses to repress, as the death of Grandpa Edwin Hoover is only a mechanism to revive and spark change in the most irreverent way through Richard’s potent reliance on the absurd, where Olive is the sole metabolism of the film.

12. Disconnect (2012)

It’s a film that asks the right questions in the most deviant manners with a prognosis for the worst in the most stylized-edited way. A pack of philosophical scenarios drive the sole natures of their characters.

This beautifully edited film chooses to punch where it hurts, for their answers are the ones that are dormant in every path we manage to oblige ourselves onto. There is something more here than what is right or wrong, but it’s what someone can actually do with right and wrong in a nonlinear fashion that manages to ripple onto its characters, with everlasting consequences where hope is the elusive resource that faith must shuffle itself with.

13. Faults (2014)

A bizarre film in any selection, this ideological product grows with a deadpan sense of humor, where its beautifully selected cast dulls a shining light in any plot in the most Nietzschean way.

The ideas shown here are clear insights for what evolved propaganda can do to ourselves. The idea of seduction is worked at its finest here through the path of questioning to complete exhaustion.

When the spiral reaches its end, it only finds that there is another level, and so on. The faults sensed here, as well as the fates of its characters, are only a layer to the grand spiral that aligns in what coaxes the regretful choices and their Borges-esque personal labyrinths.

14. Filth (2013)

Like “Donnie Darko”, this film works on what it is to exist and not to be there at the same time; it’s only the filth that envelops Bruce in a sort of “Trainspotting” manner that seems to vibrantly shift in a clear delusion of what life is, and not what could be. Here, the movie seems to work with the door ajar, never choosing which aspect is better, opting for the life in filth.

There is a great deal of Confucianism here, where a “transmitter who invents nothing” is what Bruce is, only that this void is actually what he transmits, and for human purposes, is completely sane to then live in the filth.

The mayhem, chaos, disorder and convoluted arrangement of this film make it stand for an unchangeable manner that could trace to the very foundations of mankind, and more precisely, “malekind”.

15. The Place Beyond The Pines (2003)

Not the most appropriate Father’s Day film, this film that is similar to “21 Grams” approaches questions of familiarity and remembrance, within the whereabouts of family in a way that even films like “The Godfather” was afraid to embrace, dwelling on the ideas of sense and vindication in strange ways.

Ryan Gosling and Bradley Cooper are only abstract sides of the same coin, lenient stages of their purpose. Their credit is that their hearts, the biological ones in each of their offspring, is crafted far away from the Platonic Cave, realizing that playing with the rules of man can be as devious as instead going the long way with God’s greater master plan, opting for their legacies.

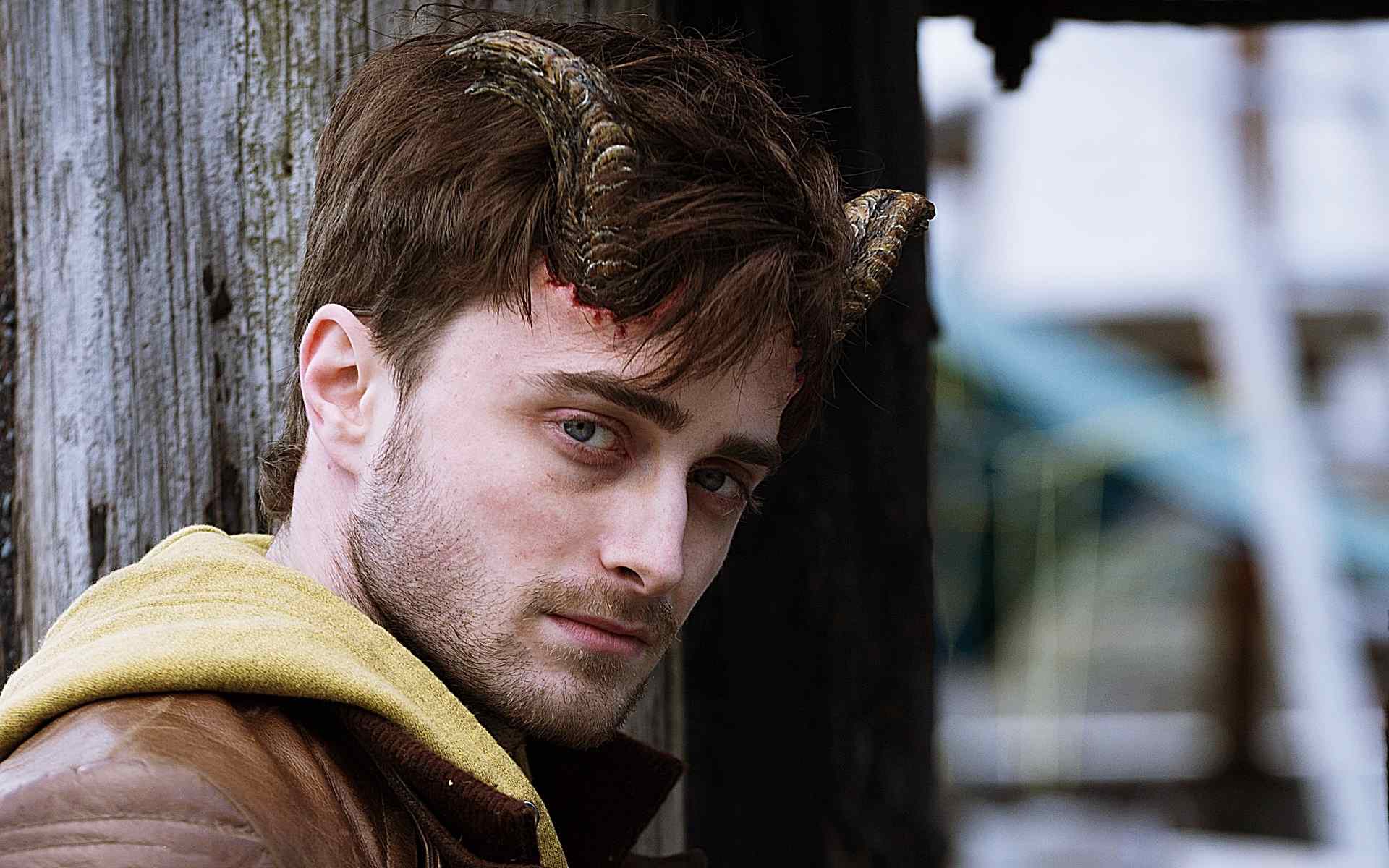

16. Horns (2014)

Though there’s a bit too much here and there in this film, this mythologically-approached adaptation can work on levels where metaphors remain unclear, yet drawn into a perspective of morphing each character into an ideal.

The aesthetics here obey the law of Renaissance Philosophy, where the focal point of guilt is malleable. The liquid state of things that Bauman points out works here to reinvent the nature of the absurd, as it is proven time and time again that the work of man in himself is mythologically perpetual and never-ending.

17. The Double (2013)

Dostoevsky’s work here answers more than asks in this film, drawing extensively from a rich vein of ideas that ask about the place and nature that each of our selves are occupying at an specific time.

The sense of consciousness here works on a more contemporary alignment, narrowing the ideas of Locke and Heidegger to shape ideas through actions, where the menacing sense of disturbing behaviors is better identified in a protected state.

The guilt and regret that live through the sides of the double manages to constantly shift what is right and wrong in one half, but the right element to balance here must instead be where alignment seems rather improbable according to the works of their characters. For instance, choosing the lesser evil seems more appropriate in every scenario, for it wrestles with a truth at least that cannot be judgmentally broken. The linear ethics must be met here with a vertical sense of adaptation.

18. Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

Perhaps the most intimate study of a character from Paul Thomas Anderson and borrowing fine dramatic work from Adam Sandler, this beacon of love stands for its meaningfulness rather than spectacle. The fireworks here are just part of believing in love after all.

The fate that Sandler gives through his portrayal is the silent line that manages to keep us interested in the greater destiny of love itself. What Anderson achieves here is for us to worry for one of the cogs of mankind, for Sandler depicts that love is born yet not comprehended; it shall never be understood as an Aristotelian gem, but an encapsulating smog.

19. Adore (2013)

There’s a great deal of Freudian concepts sprayed evenly through this film. Here the effort of asking and responding is kept silent, for vibrant curiosity is the only matter that stands firm in this movie.

The phantom that breathes through the shape of the mother is only a projection of what really feeds through the individual, but in their quest to live through the clandestine and forbidden is that the lesser self, the more mundane half, becomes entirely omnipresent.

20. Submarine (2010)

It is strange to find such an intimate and colorful tale not done by Wes Anderson, but here, funnyman Richard Ayoade explores the many layers of depression in a way that rather that delves on the sickness and confronts it with meaningful protections of misplaced (but still omnipresent) hope.

Reductionism hasn’t been at its finest since this film, which narrows expectations with desire in a ubiquitous way that plays with the territory of the unknown and the unspoken.

Author Bio: Guido Samame is an avid film critic, writer, indie music fan, producer and assistant to the professor at the Universidad de Lima in screenwriting. Currently residing in Lima, Peru; Guido can be found walking or driving around the sun thinking about some story to some nice tunes you have probably never heard of. You can follow Guido on Facebook, Snapchat or Instagram as @Guido Samame or @guidosamame.