21. Samurai Reincarnation (Kinji Fukasaku, 1981)

The film is based on the novel Makai Tensho by Futaro Yamada, which also spawned three other films, the “Ninja Resurrection” anime, manga, and videogames.

Shiro Amakusa was the leader of Christians in Japan during the Tokugawa reign. When soldiers of the regime slaughter thousands of them, Amakusa renounces God and succumbs to the forces of evil in order to exact revenge.

In that fashion, he resurrects a number of legendary fighters and characters, including legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, ninja master Goemon Ishikawa, and the monk Inshun. In their way stands an equally legendary fighter, the one-eyed Jubei Yagyu.

By the late 70s, the realistic samurai film era, as celebrated by Akira Kurosawa, was in decline, with supernatural sword and sorcery films taking their place. “Samurai Reincarnation” is a distinct sample of the category.

Kinji Fukasaku directed in exploitation fashion, including female nudity, a plethora of bloodbaths, amputations, and decapitations. The action scenes are impressive, particularly the final one, which takes place in a burning castle.

The cast includes cult favorites Sonny Chiba, Kenji Sawada and Ken Ogata, and Hiroyuki Sanada, who won an award from the Japanese Academy as a newcomer.

22. Alien vs. Ninja (Seiji Chiba, 2010)

A comet crashes in a Japanese forest, bringing aliens that take over the bodies of dead ninjas and threaten to kill every ninja village in the area. A team of ninjas, headed by Yamata, Jinnai, and Nezumi, must face them along with another team headed by Rin.

Seiji Chiba directs a nonsensical “trash” film that glorifies its status by actually presenting men in lizard suits fighting men in leather and lycra suits, not to mention the presence of zombies and some English speaking by the possessed ninjas. Humor is everywhere to be found, obviously, in a picture that was exclusively shot with a digital camera.

On the other hand, the battles are impressive and the action could even be described as elaborate, despite its preposterousness.

“Alien vs. Ninja” was the first production by Nikkatsu’s label Sushi Typhoon, which later produced “Cold Fish” and “Helldriver”.

23. Love Kill Kill (Shinya Nishimura, 2004)

Satoshi Minagawa is job placement office worker who has a mania for collecting porn. One day, Sayuri Maejima, a very beautiful but unorganized person, visits his office and he falls in love with her. Nao Aiba is a high school student who wanders around town with her friend Mami instead of attending school. Eventually she meets Satoshi, who tasks her with befriending Sayuri to find out her interests in order to use them to seduce her.

Sayuri has a brother, Kou, who grows magic mushrooms and sells them to strangers. Nao meets him and the two of them realize they are both homosexual. Furthermore, while Satoshi has begun dating Sayuri, Nao realizes she is in love with her.

Shinya Nishimura directs a romantic coming-of-age story in Japanese style, combined with altering sexuality, drug use and peeping.

Cult favorite Kanji Tsuda, who is always great in portraying “perverted” characters, gives a great performance as Satoshi.

24. Sex Jack (Koji Wakamatsu, 1970)

Koji Wakamatsu stated that for this film, he wanted to show that government moles always infiltrate revolutionary movements.

However, being the exploitation mogul that he is, he decided to portray this fact by placing a group of students who called themselves the Rose Colored Regiment in the house of a mysterious woman, where they proceed to have sex with her consecutively without caring for her consent, although Wakamatsu does not make her wishes clear.

Wakamatsu also wanted to criticize the false sexual liberation of the 60s, and in that fashion he presented a number of characters who are sexually insane, and whose sexual liberty is purely an illusion that leads to the New Fascism.

Wakamatsu always had a knack of combining exploitation themes of sex and violence with politics, and “Sex Jack” is a distinct sample of that fact.

25. Samurai Zombie (Tak Sakaguchi, 2008)

The second collaboration between Tak Sakaguchi and Ryuhei Kitamura after “Versus” resulted in a film very similar in themes and aesthetics with the splatter and cult favorite.

A family on vacation runs from a group of bank robbers near an isolated forest. The gangsters take the family as hostages, but soon after, a samurai rises from the grave and attacks them. Sometime later, policemen who were pursuing the robbers arrive in the same place, only to be ambushed by a zombie who seems to have organized everything.

If the concept of pairing samurais, zombies, cops and thieves, and an innocent family was not enough, the creators also included some humorous moments, chiefly resonating from the policemen who, at times, even address the camera.

Although the film is somewhat restrained in terms of gore, at least when compared with the creators’ other splatter works, the constant and unexpected killing of various protagonists largely compensates for the lack of constant bloodbaths.

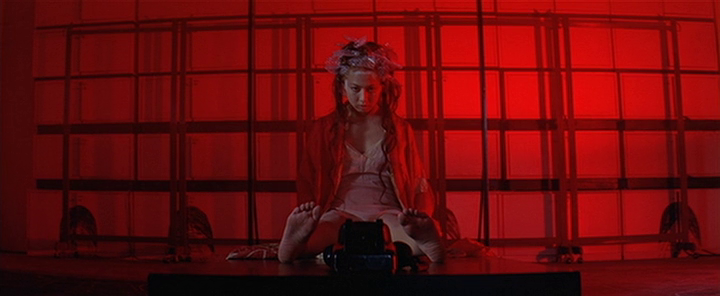

26. Ritual (Hideaki Anno, 2000)

Based on an “autobiographical” novel by Ayako Fujitani (Steven Seagal’s daughter) who also stars alongside director Shunji Iwai, and directed by Hideaki Anno, director of “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” “Ritual” is a firstly a cult film because of its production values and then as an actual movie. Furthermore, it is probably the most artistic one of the list.

A spiritually “spent” anime director returns to his hometown where he meets an eccentric and suicidal young girl, who is so invested in her extraordinary routine that she has lost almost every connection with reality. This routine includes her everyday saying that tomorrow is her birthday, lying on train rails, and other peculiarities.

The director is strangely drawn to her rituals and the two of them slowly fall in love. Anno directs a very strange romantic film, once more focusing on solitude, fear, and social exclusion. The film has an anime feel, both in terms of story and visuals, since the bright and motley colors are omnipresent in every aspect of the girl’s life, from her clothes to the abandoned department store where she lives.

Ayako Fujitani is great in portraying a very eccentric character, who is actually and metaphorically herself.

27. Crest of Betrayal (Kinji Fukasaku, 1994)

Kinji Fukasaku combined two of the most renowned stories in Japanese culture, the “Tale of the 47 Ronin” and the ghost story of “Yotsuya”, creating a film that is as cult as it is elaborate.

The script revolves around Iemon, one of the 47 masterless samurai, who sets aside the revenge designed by the group to marry the granddaughter of Yoshinaga, the perpetrator of his former master’s execution.

However, before the wedding, he kills a prostitute he was involved with, in a hideous and torturing fashion that disfigures the woman before her death. On his wedding night, the ghost of the woman returns to torture the couple.

Fukasaku combines the two stories ingeniously, presenting a masterful film that deals with socio-economic themes, morality, and the supernatural, all disguised as a costume drama.

The film is splendidly cinematographed and the actors perform in wonderful fashion, in a production that won seven awards from the Japanese Academy in 1994 and a number of awards in other competitions, and is largely considered as the best work of the cult favorite filmmaker.

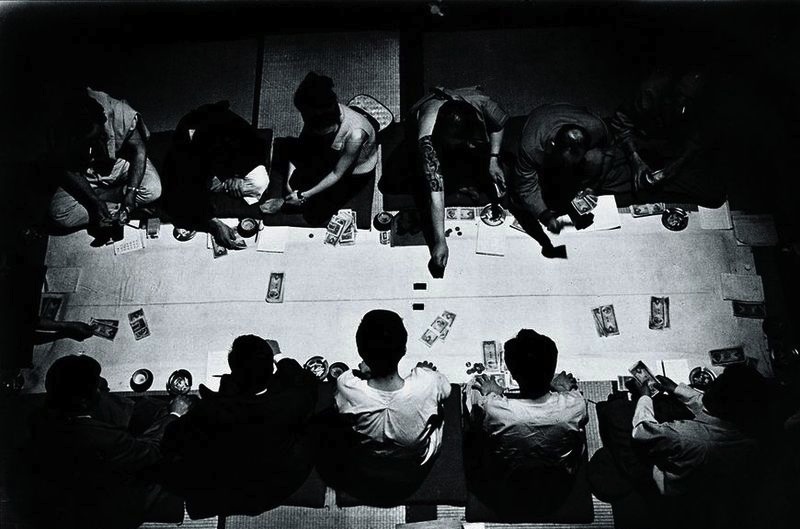

28. Pale Flower (Masahiro Shinoda, 1964)

In one of the distinct samples of Japanese New Wave, a Yakuza named Muraki is released from prison and finds himself in an illegal gambling den. While there, he meets Saeko, a mysterious woman with a gambling addiction. The two of them strike a peculiar relationship, which seems redemptive in the beginning, but ends up being mutually destructive.

Masahiro Shinoda directs a very dark film, both in cinematography and plot, since most of the movie takes place at night and indoors.

Mariko Kaga plays a character who rarely shows emotion. However, during the two scenes that she’s in, her unearthly laughter makes for one of the most memorable acts in the film. Ryo Ikebe is also great in his role, in a genuine noir film.

29. The Steelman from Outer Space (Teruo Ishii, 1957)

Japan’s first onscreen superhero could not left off this list, in a film that spawned eight sequels, manga and American adaptations, and became popular in France and Italy.

The Steelman is a human-like creature created in the Emerald Planet from the strongest steel available, in order to fight evil. In this first installment, he arrives on Earth and assumes a human’s identity, in order to discover and stop terrorists who threaten to destroy Japan with the atomic bomb.

Watching a black-and-white 1957 Japanese science fiction film is a cult act by itself, but for the audience at that time it was a horrifying experience, since Teruo Ishii used footage of atomic bomb tests and explosions, while the memory of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was still fresh.

Furthermore, the costume of the superhero was stuffed in the crotch area, because the producers thought that this would attract a female audience, thus resulting in an appearance that seems quite ludicrous. Ken Utsui, who plays the part of the Steelman in all of the films, hated the role and refused to talk about it until his death.

30. Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (Shuji Terayama, 1971)

Shuji Terayama was a prominent member of a movement that occurred during the 60s in Japan, with the shooting of noncommercial experimental films, individual efforts that theaters in their overwhelming majority refused to screen.

In his first feature film, the protagonist is a nameless young man with a highly dysfunctional family. His grandmother is a shoplifter and his father, a war criminal, has an intimate relationship with a rabbit, along with the protagonist’s sister.

The young man is determined to achieve something in his life, in contrast to the compromised members of his family. In his efforts, he becomes disillusioned about the world and society.

Terayama shot the film with a number of peculiar and unprecedented (for Japan) techniques, like the opening scene with the protagonist talking directly to the audience.

Furthermore, scenes like the one with the burning of the American flag and the discussion about sports ball size give the film an anarchic visage, while presenting a metaphor for Japan’s descent into materialism.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.