8. Murmur of the Heart (1971)

French director Louis Malle graduated from award winning documentarian (including an Oscar) to a director of feature films in 1958 with the crime classic Elevator to the Gallows. He always had a solid career with multiple Oscar nominations (though, shamefully, never a win for his excellent work in the fictional medium).

However he seemed to truly come into his own in the 1970s. It can be no coincidence that during that period, by his own admission, he started making films which related to his growing up years in wartime France and the years just after.

Murmur of the Heart tells the tale of Laurent, a 14 year old boy living in the Dijon region of France in the mid-1950s. Laurent (Benoit Ferreux) loves many of the things the young Malle loved, such as jazz, is precociously bright and has an excess of affection for his warm hearted Italian mother (Lea Massari), which offsets his less than loving relationship with his uncaring father (Daniel Gelin) and contentious relations with his two older brothers.

A case of scarlet fever leaves him with a heart murmur and during his convalescence at a spa with the mother to whom he is getting even closer, an incestuous episode occurs. This was a quite controversial point at the time (and still delicate today) but the treatment is so honest and sensitive that it displayed just what a true artist can do with even the most sensationalistic subject matter.

Malle, who also wrote the film, admitted that much of it was autobiographical (though not the incestuous episode). An extra element adding to the quality is the superb jazz score by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gilespie (and Malle often used great jazz men to create scores).

9. Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1971)

Though not out of the closet to the general public at the time, John Schlesinger was quite often open in studying sexual mores in the modern society of the age in which he filmed. Today many find 1965’s Darling and 1969’s Oscar winning Midnight Cowboy (controversially X rated at the time)to be rather dated and shallow. Sunday, Bloody Sunday was widely thought to be somewhat lesser in the director’s cannon at the time but looks better and better with the passage of time.

The plot concerns Dr. Daniel Hirsh (Peter Finch in his career best performance, despite being cast after the picture started when two high profile actors did not work out), a London based Jewish doctor well into his forties. He is also gay at a time and in a place where that was not an easy situation. The plot also concerns Alex Greville (Glenda Jackson, also hitting a career high), an employment counselor divorced and in her thirties, also not a comfortable situation for a woman in any era.

The two share an answering service (manned by silent and early talkie Hollywood star Bessie Love!), a lot of friends…and a relationship with Bob Elkins (Murray Head), an attractive artist in his twenties who is quite casual about his two affairs (and sexual orientation). Though the situation was very much of its time and the film is layered with much early 70s detail the depth of feeling for the characters and their circumstances transcend the surface trappings of the film.

As the film unreels it becomes alarmingly clear that Daniel and Alex are quite aware of each other and their respective presences in Bob’s life and that he knows that they know. However, the two older people are caught in a longer range situation where they have few options. Love or whatever may not come calling again and they both grab at it with both hands, no matter how humiliating.

Many over the years have faulted the casting of handsome but uncharismatic Head (normally a stage actor) but his blah performance is a big part of the film’s point: this pretty face and empty heart has taken unfair advantage of two venerable but infinitely more worthwhile people. The wonderfully literate script was by distinguished film critic Penelope Gilliat. The film’s distributor found it distasteful and gave it little attention but it has survived the years in great style.

10. Cries and Whispers (1972)

As the Seventies began, Ingmar Bergman started his fourth decade working in film with his reputation as one of the world’s finest film makers at high ebb. The decade would prove to be rather uneven with a very brief and unhappy stab at Hollywood near the beginning and a most humiliating run in with Swedish tax authorities in 1976, which lead to Bergman leaving his native land for a few years (and he was like a complete fish out of water working anywhere but Sweden).

However, the high points were films rated among his best . Perhaps the best of them all was Cries and Whispers, which, along with 1966’s Persona, embodies the long held belief that no director understand the psychology of women better than Bergman. The casting of the film’s women (and others) includes many of Bergman’s longtime players.

The story is set in a gracious estate in the countryside of 19th century Sweden. Agnes (Harriet Anderson) is dying painfully of what appears to be cancer. Sisters Karin and Maria (Ingrid Thulin and Liv Ullman) have come to help supposedly. However, each comes with significant emotional baggage as individuals and they and the dying sister have lots of family issues. Considerations of property also don’t help.

The one person who seems to give the dying woman the care and thoughtfulness she needs is the family maid, Anna (Kari Sylwan), who has suffered great loss in her own life. Bergman took what could have been a familiar melodrama and guided it into a deeper place with many over the years comparing it to the work of the great playwright Anton Chekov.

His actors, including long-time Bergman staple Erland Josephson in addition to the actresses he had used so often, are employed to their best advantage. Though Bergman would direct three films which won Best Foreign Film Oscars, this would prove to be his only nominee for Best Picture and was a hit throughout the countries in which it played.

11. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)

The Seventies would prove to be the last decade for the great Spanish born surrealist Luis Bunuel and he, sadly, would not make it through the entire time span. However, his last films were among his best and Hollywood finally began to pay some respect in the form of Oscar…nominations.

He finally won, for the only time, with The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (ironically, he had planned to retire after Tristana in 1970 and, typically, did not attend the ceremony and later took a picture with the award in which he completely sent it up).

As many have noted, the plot of this one completely inverts the premise of the director’s 1962 classic The Exterminating Angel. In that one the rich and privileged were mysteriously trapped in the home where an elegant dinner party was held and slowly starve. In this one, the hoi polloi get to move around as freely as they like but end up equally starved since every attempt at dining is foiled by one freakish occurrence after another.

Of course, this is a comment, as in the earlier film, on the spiritual emptiness of the upper class. Along the way many jawdroppingly wild things happen such as an archbishop taking a part time gardening job to make ends meet and a few coolly casual murders in the name of propriety.

The difference of the decade between the earlier film and this one showed that the basically fine and special qualities Bunuel has always exhibited (such as his savagely funny surrealist wit) had remained intact but had also acquired a highly professional sheen married to an immaculate sense of technique.

12. Chloe in the Afternoon (a.k.a. Love in the Afternoon) (1972)

French director Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales series remain an art house delight decades after their premieres but, at the time, only the final three were well known since the early ones were shorts or very independent efforts seen by few. However, the final three were quite popular and commented upon and Chole (or Love) in the Afternoon was perhaps the most popular.

As ever with Rohmer, the film deals with a familiar, if not clichéd, situation but treats it with great depth and sensitivity. Frederic (Bernard Verley) has it all: he’s youthful but a successful lawyer, he’s married to a lovely young teacher and they have an adored little son and new baby on the way. However, it doesn’t seem to be enough, especially when there’s Chole (Zouzou), a liberated woman who had once been attached to an old friend of Frederic’s.

It’s plain from the start that Frederic isn’t so much pulled towards Chole per se as the time she represents in his recent past life when he was as free as the wind and enjoying every moment of it all. The film comes to an expected conclusion but this effort makes it all feel as though things truly could have gone another way and the deciding factor hinges on one small but significant gesture which rings quite true.

The film is wise enough to know that the conclusion does not tie up everything for all concerned and that there is residue to consider thereafter. To see what this film might have been like in the wrong hands, see, for instructional purposes only, the 2007 Hollywood remake (!), I Think I Love My Wife.

13. Solaris (1972)

Science fiction was once a relatively simple genre onscreen. Just show something futuristically fantastical on screen and make it look good and ring true and the film was home free. However, 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey upped the ante considerably. Through the years it has become plainer and plainer that, though there are worthy contenders, no other sci-fi film will ever quite live up to 2001.

However, the closest contender by far came from another great filmmaker, one who, like 2001’s Stanley Kubrick, didn’t ordinarily make films in the sci-fi genre. Andre Tarkovsky may stand second only to Sergei Eisenstein in Soviet film history as a maker of fine films. However, like his predecessor, Tarkovsky ended up with a limited filmography (and subsequently a disappointed and shortened life) thanks to the authorities of his homeland.

After his 1966 masterpiece Andrei Rublev was banned and virtually unseen for decades, the director was left in bad financial straits. He needed a money maker and decided to work in a popular genre. He chose an acclaimed short novel by Polish writer Stanislaw Lem . The plot concerns a space station orbiting a strange and uninhabited planet called Solaris.

The atmosphere or pull surrounding the planet has caused the three man crew of the station to be paralyzed emotionally, requiring weary and resigned psychologist Kevin Kelvon (Donatas Banionis) to be sent to join the crew, a job he accepts since he has released his hold on all earthly ties.

He soon discovers the two surviving crew members (the third had committed suicide just before Kelvin’s arrival) are emotionally withdrawn and the newcomer soon discovers why: Solaris causes past memories to be summoned up in the minds of living beings in its orbit and can resurrect long dead figures from the personal past.

Kelvin is stunned to find his long dead wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) ,also a suicide, has been summoned to confront him by the planet. Those who worried about Tarkovsky selling out need not have feared. Just an outline of the plot shows that the premise is a pretext for exploring human emotions and relationships in a unique way due to the science fiction setting. (Also, the ideas and little else were used from the novel, much to Lem’s displeasure.)

Like all Tarkovsky films, Solaris is slow, deliberate, cerebral, oblique, subtle and complex. The viewer must stick with a Tarkovsky film but the rewards for doing so are ample. In 2002 Hollywood decided to remake the film just in a faster and simpler style. The results weren’t bad but one look at both shows how special Tarkovsky truly was as a film maker.

14. Day for Night (1972)

After a stunning first decade (the 1960s) France’s Francoise Truffaut had another fine spell during the subsequent ten year period. The sad irony is that it would also prove his last full decade as a brain tumor would cruelly end his life and career prematurely in 1984 (and prevented him from working long before it killed him).

Though his films of the Seventies didn’t have the flash and instant cultural recognition of his work from the earlier decade, those films were, on the whole, more solid and substantial works. Any one of several films he made during that time could fill this slot (and most of his famed autobiographical Antoine Doniel films came from this time) but perhaps the most fitting is the one great film which centered on his greatest passion: film.

Day for Night (which is a film making term used in cinematography) concerns the trials, tribulations, joys, triumphs and plain hard work which goes into making a film. In this case the film is apparently a light romantic comedy entitled Meet Julie. Whether it turns out to be any good is beside the point since the film is about how the cast and crew work together to create something decent which can be projected.

There is the harried young director (Truffaut’s eternal alter-ego Jean-Pierre Leaud), the hot young actress playing the lead (Jacqueline Bisset, cast to type), who has a romance on the set, the aging diva (a superb, award winning Valentina Cortese)not allowing herself to be put out to pasture without a fight, a sudden and unexpected death, lots of production difficulties, and….all the things which often happen while a film is being made.

Truffaut is quite knowing and skillful in depicting this entire situation but is also funny and loving,also (and Cortese’s character, while true to life, is also very humorous). The director often made his personal life and history part of his work through his films but this was the one time the work itself became the subject and it tells much about Truffaut the artist and film lover.

15. The Mother and the Whore (1972)

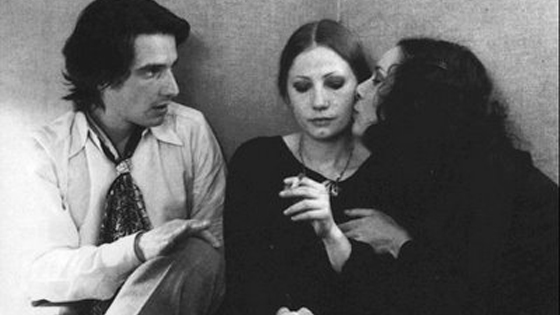

France’s Jean Eustache did not have a prolific career to say the least. In fact, he rivals his early talkie era countryman Jean Vigo in being most remembered for the least amount of work. Eustache, an unsettled man who ended as a suicide, directed a few shorts and two feature films. However, the first of the two is one few who have ever seen it will have forgotten. Blending Truffaut, Rohmer, and the great American indie film maker John Cassevettes,

The Mother and Whore (which might have been better translated as The Madonna and the Whore) takes a somewhat trite situation and works miracles with it. Set in a summery Paris in the early 1970s, the film finds Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Leaud, who had quite an eye for great directors) living with the wife-like Marie (Bernadette Lafont) and is rather happy but also drawn to the very liberated (especially sexually) Veronika (Francoise LeBrun).

He and Marie profess an open relationship and he allows her to know that he is having an affair with Veronika and she claims to be fine with it. However, the feelings of all involved soon enough erode and a long simmering confrontation and discussion (or discussions) ensue.

This is not really a plot film as much as a film concerning the intricacies of human behavior. With a running time of nearly four (!) hours a lot of human behavior gets discussed and much of it was improvised by the actors under the writer-director’s guidance The basic situation was quite familiar to Eustache and, in fact, Miss LeBrun was virtually playing herself since she had been involved with him in the real life situation (and was not pleased with how she was handled in the finished product).

The concentration on realistic detail and the quest to explore the character’s behavior made this a unique and special film. The potential shown here made the early end of its maker all the more tragic.