25. Rome, Open City (1945)

The term “Neo-Realism” has been previously used on this list but, with this entry, the real thing is addressed. In the waning days of World War II the Italian film industry was still interested in creating cinematic art, in the face of the horrors of war and deprivation.

The Italian cinema up to this point in time, with notable exceptions, had been rather ornate and preferred to tell stories of the rich, famous, and glamorous. For an Italy torn by war, chaos, civil unrest, and various types of violence and poverty, this type of film was totally unsuitable.

Younger film makers sought a new style and were determined to tell the story of the Italy of that era and of the uneasy peace which followed. Fortunately, the type of film they wished to make took little funding, which is what was available.

They shot mostly on authentic locations, often in the streets, and employed cast of amateurs or amateurs mixed with professionals who had not been overexposed. The camerawork was not formal and the emphasis was on the natural grit of life in the less lavish sections of Italy, especially its big cities.

As previously noted, de Sica was at the top of the list for this group, but there was another name virtually as prominent and that director-writer was Roberto Rossellini. Rossellini was a dynamic and colorful figure indeed. He was a worldly wise sophisticate with a way with women (as the world soon discovered) who was also a scholar and teacher and a cinematic artist, though he would be much more tied to Neo-Realism than de Sica in the eyes of posterity.

His big breakthrough came with Rome, Open City, a heartbreaking film concerning the last days of the war as the citizens of Rome tried to survive amidst Fascists both homegrown and imported (German), while the enemy, whom many would welcome, comes ever closer and resistance fighters bravely, and often futilely, to oppose the doomed, but still vicious, oppressive rulers.

Rossellini was equally brave as this film has the feeling which can only come with something honestly ripped from real life. The cast seemed to have been taken from the ordinary people of Rome but, unlike later films in the movement, they were mostly professionals.

The greatest of all in the fine ensemble was one of the great forces of nature ever unleashed on the cinema: Anna Magnani. She had been acting for some twenty years in theater and film when her all-out portrayal of the tragic pregnant mother-fiancée figure in this film put her over the top (and over the top describes her earthy visage and acting style, though she is among the very few to make over acting a virtue).

Though time was against her, she would become a top international star for over a decade and win an Oscar for 1955’s The Rose Tattoo (a Hollywood film by way of an admiring Tennessee Williams).

As for Rossellini, he made two much acclaimed similar film, the touching war anthology film Paisa in 1946 and the affecting Germany: Year One in 1948 before the scandal of his romance with Ingrid Bergman derailed him a bit. He came back with some fine films and astounded with some superior historical films made for Italian television late in his life. However, his Neo-Realist days remained his finest hour.

26. Dead of Night (1945)

One of the joys of any art house repertory are the films created by Ealing Studios in England from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s. Many think that Ealing existed for only for that short period but the studio had, in fact, been around much longer, albeit as one of the infamous “quota quickie” studios which had been created to produce the number of home grown films the government demanded in order to import Hollywood product.

For much of the early years the studio got along by producing cheap comedies with mostly wheezy music hall performers. The arrival of new executive (Sir) Michael Balcon during the 40s caused things to start looking up and the studio began to come into its own with the remarkable 1943 war film Went the Day Well? (told as a flashback by victorious British citizens after the war was over, which it wasn’t at all at the time of filming).

Ealing was a dream of a studio. It prized writers, directors and character actors, about in that order. It made intentionally modestly scaled and thoroughly civilized pictures filled mostly with nice people joining together to solve common problems. That doesn’t sound at all exciting and to modern audiences’ maybe it isn’t, but the wry good humor and observance of average people and their triumphs and foibles which made up most Ealing films is still a joy to those who can catch the vibe of what they were trying to achieve.

Oddly enough, the studios big breakthrough was a real anomaly for both Ealing and the British film industry. The British have always been rather reticent concerning horror, to say the least. Ealing did not venture into the genre any more than any other film company…except for one great time. Perhaps the studio wanted to showcase several short stories by well known British authors which couldn’t really be expanded into features on their own, so a unique omnibus was concocted.

The film, Dead of Night, features a befuddled architect journeying to a farmhouse deep in the countryside. Everything and everyone feels familiar and he realizes and tells all present that he has dreamed of all of it beforehand. Some are skeptical, mostly a psychiatrist in the bunch, but all start to relate various encounters with the supernatural they have had. (Why some of them doubt the man after the stories that they tell is a head-scratcher.)

The framing device and the various stories each had different directors and writers. The directors included soon-to-be Ealing staples such as Alberto Cavalcanti, Robert Hamer, Charles Crichton and Basil Dearden with the writers including Angus McPhail, T.E.B. Clarke and John Baines.

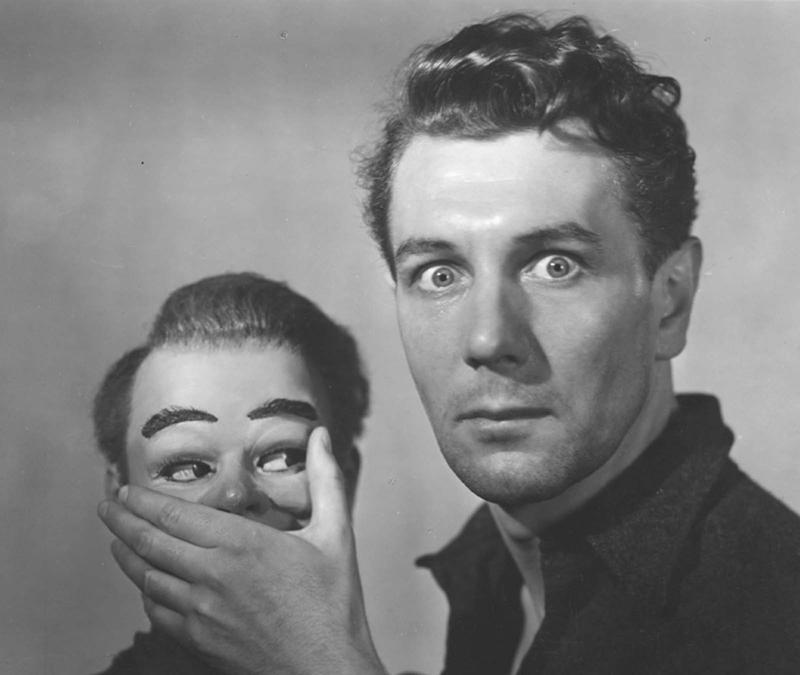

The cast was made up of such stalwarts or stalwarts to be as Mervyn Johns, Frederick Valk, Googie Withers, Miles Malleson, Basil Radford and Naughton Wayne and a young Sally Ann Howes. However, what galvanized the project was the work of a young and still rising star recruited from the theater, Michael Redgrave. His is the final episode of the stories told, under Cavalcanti’s direction, and involves a ventriloquist who is either going mad or who’s (really ugly) dummy is possessed.

Those who have seen similar stories on, say, The Twilight Zone won’t be amazed at the plot but Redgrave blows everyone else right off the screen. The framing device comes to a wild, memorable climax as well. Ealing wouldn’t pursue this path but it put them on the map and made many wonderful films possible.

27. Le Silence de la Mer (1947)

Jean-Pierre Melville was a most colorful figure and a fine director, mostly of crime based films which were also in depth portraits of characters, often male criminals, caught up in tense situations outside of the province of the law.

One odd thing about his career is that his beginnings in film making and first notable films weren’t in that genre and style at all. He had served in the French resistance during World War II and that experience colored both his work and the remainder of his life (which, sadly, wasn’t that long since he died of a heart attack at 55).

He entered the theatrical and film worlds after the war and took on the name Melville (after Moby Dick’s author) in place of his native Grumbach and sought work first as an actor and then as writer/director. He would eventually fall under the auspices of the great Jean Cocteau, who would provide the opportunity to direct his first big hit, 1950s acclaimed Les Enfants Terribles.

However, Melville had made his directorial debut three years earlier with a film which did well with the critics, less so with the public, and which is now considered one of the great debut pictures. A fellow resistance fighter who went by the pen-name of Vercours (Jean Bruller) had penned a novel which is now considered a classic of resistance era literature.

The novel, Le Silence de la Mer, tells the story of a Nazi officer billeted in the home of an aging Frenchman and his adult niece. No, the German and the girl do not fall in love. In fact, that is far from the story. The French natives adopt a passive-resistance stance toward the German officer, icily refusing to acknowledge him in any way they do not absolutely have to express. This includes speaking to him.

The sad irony is that the man turns out to be a decent human being who happens to be servicing a horrible cause. Sadly, war is war and acknowledging his humanity is a luxury the two natives can’t afford. This sounds simple and the technique is deceptively so. There are only three actors (Jean-Marie Robain and Nicole Stephane as the French and Howard Vernon in the vital role of the German) and the action is largely confined to the living room of the home, the one place the two family members must tolerate the intruder.

Vernon carries the load as his character does almost all of the talking and his narrative playing over the action both tells and advancing the plot. The miracle is that the film doesn’t come across as at all static or dry. Melville obviously had a cinematic gift and, though it wouldn’t really flower for a half a decade, he would make a fine contribution to cinema, worth of the fighter was he had been.

28. La Terra Trema (1947)

Though he had show such promise with Ossessione, that fim’s icy reception by the Fascists government hampered Luchiano Visconti’s career for a while. However, when he finally did return to film making in 1947, he delivered the film which truly set him on his career course.

As would be the case throughout the early part of that career, Visconti chose a novel which dealt with the plight of poor, here fishermen on the Sicilian coast of Italy who, in trying to go into business for themselves, rather than labor under repressive wholesalers, find disaster.

The results will turn out to be realistically tragic as economic pressures fan long brewing family issues. Visconti knew that the Neo-realist style as such wasn’t quite right for this story which didn’t touch on war and post-war concerns, so he adapted it somewhat. The locations are real and the performers are non-professionals recruited from the ranks of the people the story depicts.

At 165 minutes, the picture is way longer than the average run of Neo-Realist film and Visconti shows some of the operatic conventions which would mark his films. This was to be the first of a trilogy of films depicting life among the lower classes in that part of Italy. This would have been in line with the ideals of the Italian Communist party, with whom Visconti was associated.

The third part was to have ended in victory for the people and was to have been used as propaganda. However, Visconti, though a good Communist (then, anyway), was too much of an artist to go through with something false and let this story speak naturally for itself, even though its ending may not have been a crowd pleaser. He would go on to many more excellent films, most better known than this early masterpiece. However, this one can hold its own with any of them.

29. The Fallen Idol (1948)

Carol Reed was always one of the class film makers of British cinema. He was the out-of-wedlock son of noted actor Sir Herbert Beerbohm-Tree (though happily so, as the parents were bohemians, not believing in marriage). He had built a fine career in the British film industry though the 1930s and into the 40s (and he never went Hollywood, really). However, as World War II ended he truly found his métier with a trio of suspense films acclaimed to this very day.

1949’s The Third Man has always been cherished and beloved by critics and genre (and fine film) fans. 1947’s Odd Man Out is finally breaking out of the cult classic mold to become an acclaimed Brit-noir masterpiece. That leaves the middle film of the trilogy to find its way back into the cinematic limelight.

Make no mistake, though: The Fallen Idol is every bit their equal. Reed’s great collaboration partner was one-time film critic turned much acclaimed author Grahame Greene (who always downplayed his film work) and for this effort the author adapted his own short story The Basement Room (which the writer admitted had an inverse arc from the film).

The plot centers on a young boy named Phillipe (a non-professional named Bobby Henrey whom Reed, who had a gift with child actors, guided to a remarkable performance). He is the child of an ambassador living in an embassy in England. His parents and most of the staff of the embassy are way and he has been left in the care of an in service couple named Baines. The boy adores the kindly Mr. Baines (an excellent Ralph Richardson) but he and Baines loath the ultra-hateful Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel, who almost steals the show).

In fact, Baines has sadly fallen in love with a beautiful and warm Frenchwoman (French star Michelle Morgan), but he is honorable and torn due to his marital obligation. All the parties are on a collision course to tragedy, which becomes magnified and intensified by the child’s innocent and confused attempts to help his adult friend.

The child, in fact, is the key to the film, not only due to the young actor’s fine performance but also due to the fact that the film so convincingly enters into the boy’s delicate and limited world. (The classic western Shane in 1953 would employ the same conceit to the same heightened effect.) Reed, Greene and all of the actors are at their best here and this film ends up a quieter entry in Reed’s triptych of masterpieces.

30. Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)

Ealing Studios once again appears on this list and once again shows up in the form of a film which is an anomaly. However, many, many reckon this entry to be their finest hour, which is ironic in so many ways. Unlike so many Ealing films, this one is not about decent, average people.

The black comic plot, taken from a 19th century novel intended as a serious narrative, focuses on the vengeful cast off black sheep relative (Dennis Price) of a really loathsome and haughty family of nobles in Victorian England. He watches the family resentfully for years until one day an interaction with an unsuspecting and particularly hateful member of the brood sets him on the path toward his ultimate goal: to kill each and every one of them until he collects their title and fortune!

The eight members of the family, even the one female member are all played by Alec Guinness, the one great star ever to be produced by Ealing. This is so ironic in that Ealing didn’t go for stars, Guinness didn’t much like working at the director-writer driven studio, and never was there a more unlikely star than the reticent, subtle, greatly talent man who loved theater work and mostly did character work on film to supplement his income (and four of his five Ealing films, along with those he did with director David Lean, make up the bulk of his cinematic reputation).

The direction was courtesy of Robert Hamer, one of the helmers on Dead of Night and someone who looked to have a bright future, which he sadly drank away and, despite making a few more decent films, never had another to equal this.

The film really put Guinness on the map, though Price’s performance is excellent and is the one which really holds the film together. He’s aided by a marvelously wicked Joan Greenwood as woman from the antihero’s youth who can be had at a (high) price and Valerie Hobson, not the greatest of actresses, is effective here as a woman of higher standing who can help the man’s social quest (and whom he has made a widow).

This lovingly reconstructed period piece is an art house treasure and resists competition. Plans to remake it in Hollywood in recent years (with Will Smith as a literal black sheep!) came to naught and a musical stage version, A Gentleman’s Guide to Murder, was big with critics and award givers, who, apparently were the only ones to go see it. Sometimes only the original will do.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film,cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.