20. Departures (Yôjirô Takita, 2008)

It was, in an instant, a very controversial movie from the get-go, since its production the movie was regarded by many as a “will-be” commercial failure, at least in Japan. It deals with the art of encoffining and all the ceremony preparations involved in encoffining a person. In Japan, although it is a very common and respectable ceremony, most of its people see it as an issue, and many of the persons involved in such career aren’t well-respected in Japanese society.

Takita confronted such problems and directed a very sentimental and beautiful movie about that problem, transforming it into a journey of emotions of very positive and happy emotions, while dealing with the unexpected outcome of death and its consequences in people’s lives. Takita’s direction provides a fresh in-view to a profession and activity that isn’t at all morbid or disrespectful, and actually helps the living to accept the loss of his or her loving one. It has the beauty of adding humoristic innuendo in certain parts of the movie, while maintaining a very high degree of respect for the activity.

“Departures” provides another view to interpersonal relationships and a person’s struggle to be respected within society. Although the main character is prejudiced for having such a job, his sentimental voyage to reach a state of happiness and forgiveness toward other people’s actions gives him the necessary strength to keep on doing something he ends up respecting and learns to admire.

Daigo Kobayashi is a recently unemployed cello player, who after losing his dream job in an orchestra, decides to move with his wife to the countryside to make a change in their lives. Once there, he discovers a very well paying job, where the candidate doesn’t need to have experience or a background connected with the job posted. Wrongly, he goes to the interview thinking he is applying to a travel agency, but in fact he is applying to become an assistant of an encoffiner. The more we watch the movie, the more we find out that this job not only affects Daigo’s life but also affects everyone around him.

Unexpectedly the job starts to penetrate Daigo’s mind, who in the beginning is quite scared and skeptical. The emotional rollercoaster of this job starts to affect him, enlightening him for a more pacific and altruistic way of life, helping others and changing their lives. Daigo’s childhood comes as a huge asset for his change, mainly toward his own father, channeling all the negative emotions in making other people’s lives better, but also conforming himself to his own life’s situation and past.

19. Sansho The Bailiff (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954)

It’s one of my personal favorites from one of the masters of the Japanese cinema. It tells the story of a brother and sister who are sold into slavery, ending up forced to work for an evil bailiff. They and their family are betrayed by a priestess, who by offering help convinced them to go with her on her boat, ending up being betrayed for the desperation of the mother of the brother and sister.

The movie deals with the subject of vengeance, mainly by the brother, also alerting for the Japanese feudal system and how it worked. It’s often referred as one of the finest movies ever made and, in my opinion, Mizoguchi’s greatest release. It’s one of his most aggressive movies, although it never explores physical vengeance, showing fight scenes or other type of violence. For example, “Sansho The Bailiff” explores the emotional side of the character, while maintaining a great degree of the samurai movie characteristics.

Check: another of Mizoguchi’s classics, “Life of O’Haru” (1952), which tells the tale of a woman who went through several difficulties in life and had to endure society’s discriminations.

18. Intentions of Murder (Shôhei Imamura, 1964)

“Intentions of Murder” is my favorite Imamura movie, combining a great storyline with awesome psychological details, turning this movie in a highly powerful psychological experience. The main character, Sadako, is “repressed” by her family, mainly her husband. She is used to fight for a position in a highly evolved Japan of the 60s that still has a certain bureaucracy associated to its family standards. She was a maid who fell in love with her master, so the situation is highly negative for her, having the need to fight for some sort of position within her own family. One day she is raped by a criminal.

Both start a sort of love and hate relationship, completely defying normal Japanese family standards. Although she initially hates the criminal, it seems that she starts to get infatuated by his passion for her, but she represses those same thoughts and feelings with a wish to commit suicide and by having some inclinations to kill little things. Imamura’s vision of an over-the-top character that, although being affected by her own family and by her own past, seems to defy the norm. Despite not being depicted as a coward, Sadako continues her life unhappily but with stability.

The criminal changes her views toward reality and makes a boring and cowardly life into a challenge. For that reason, it seems to me that Sadako finds this change exciting, transporting this same change into a masked “infatuation” for someone who raped her, taking a stand against her normal standard of life and also defying against her family from both past and present. Still, she finds happiness in her only child trying all the time to maintain that standard of living.

The movie is also characterized for its highly sexual content that was quite graphic at the time. It’s one of Imamura’s most daring releases that, although not as graphic nowadays, still contains some audacity with showings of naked images and sexual content, but also by depicting the normal living standard of the lower-classes of Japan of the 60s.

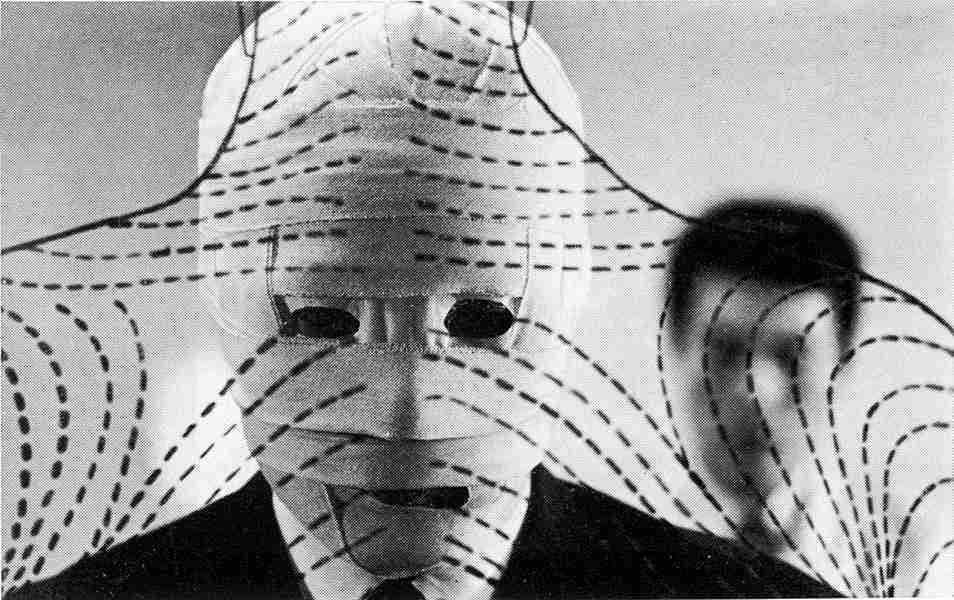

17. The Face of Another (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966)

This is another iconic release in which Teshigahara’s geniality is underrated and even ignored. It wasn’t at all accepted outside Japan and the fans were even disappointed with its outcome. Nowadays, there is a better reception but too little for a movie that is completely forward for its time, presenting an innovative and over-the-top storyline. Just looking to the concept, production, costume design and makeup department, we can see that an instant classic is a more suitable and just classification to a daring movie, which broke all accepted rules of cinema. It even broke Teshigahara’s rules and habits, creating a more urban background for a director that usually built his own scenarios and realistic concepts.

“The Face of Another” deals with existentialism and social relations. Although the main character, Okuyama, is an engineer and a professional success, his inner problems take over his entire personality, in which he is then transported to the mask he will use afterwards. Okuyama’s face was disfigured in an accident and completely covered in burns. He frequents Dr. Hira’s office, a psychiatrist who can design a mask for Okuyama to wear, which is indistinguishable from the face on which it is modeled.

The makeup department really gets the job done here; the “masking” of Okuyama is truly well designed and shot in great detail. The mask starts to take over his own personality, creating the illusion of a different being which is taking over Okuyama himself. This main story is interleaved with another story of a woman who also got disfigured.

The movie is conceptually perfect. It deals with a very difficult subject such as existentialism, while building a very fluid storyline and combining it with extraordinary performances. Also, it’s different from most movies made in Japan at that time, presenting a groundbreaking concept and filming techniques that, for not being used anymore, could be considered as daring and unusual in its field.

16. The Twilight Samurai (Yôji Yamada, 2002)

It’s by far one of the most renowned titles in recent years and one of the most awarded, having been nominated for an Academy Award. It looks into the feudal system with great detail, escaping the typical bloody fight scenes samurai movies are made of. It looks into the change Japan was going through, leaving the obsolete era to a more prosperous and modern one, symbolized by a poor samurai with no will or desire to fight. Seibei Iguchi is a petty samurai with a very low status in mid-19th century Japan. He is a widowed samurai who looks after his two daughters and senile mother.

Although honored and respected by his two daughters, some of his family see him as a nuisance, overlooking his unfortunate past. Nonetheless, he still lives a happy life and is content with what he has and the family he has, and despite being very concerned with his mother and his children’s future, he is able to live an okay life. An unexpected turn of events leads him to fight again, while worrying with his childhood friend Tomue, with whom he is in love and the instability of his clan and the revolt of the clan’s retainers.

It’s an unexpected emotional movie, looking and concentrating its plot on the sentimental side of a samurai’s life. There are few fight scenes and almost no blood, which is kind of rare in such movies, but at the same time it is able to rekindle that scent samurai classic movies have. It added a different look into the lives of the low-ranking samurai and their families, in a Japan entering in a new era, Meiji Restoration, which brought the modernization of its people and political and economical changes.

15. Battles Without Honor and Humanity Saga (Kenji Fukasaku, 1973-1974)

Regarding this choice, I’m referring myself to the first five movies of the saga, leaving “New Battles Without Honor” and “Humanity” off the list. The highly acclaimed yakuza series of movies is loosely based on real events, depicting a Japan that after the Second World War suffered a change of political, social and economic realities giving these so-called organizations a chance to prosper.

The series of movies depicts 25 years of yakuza battles, from 1946 until the early 70s, with great detail and lots of action in each movie of the saga. Each movie has 100 minutes on average, and the storyline is quite dense, mainly characterized by its many twists and turns, changes of power and bloody kills that characterized the yakuza reality of those days.

Although the plot is mainly focused on the lives of the yakuza families, there is a main character, which sometimes is left out in some sequences of the movies, due to the character’s imprisonment or due to any other event. That main character is called Shozo Hirono, a survivor and an ex-soldier from the Second World War who rises in the ranks of the yakuza society.

The storyline is truly well written and the fact that the movies were filmed and released in a two-year time period gives them a certain special degree of involvement, not only for the actors involved, but mainly for the viewers who wound up following the story in a sequence. Also, the characters really change physically; it’s noticeable that there is an aging process involved throughout the release of the movies, giving more reality to the saga. The kills and scenes of violence were purposely designed as extremely violent in order to alert to the yakuza problem that even in 1970s Japan were a reality, but also to give the series that cruel and raw look.

All the families are very well described and all the twists and turns make sense and, despite the fact that everything happens 100 miles per hour, everything is well understood and the viewers really stay on the edge of their feet to find out what will happen next. It’s perhaps one of the best movie sagas I can remember that is not only are based in actual facts, but that also created a greatly designed storyline with all the elements mafia movies should have.

Check: “Graveyard of Honor” (1975), another yakuza movie based on real events that should be here on the list, but was left out due to limited number of movies on the list.

14. The Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, 1966)

Okamoto’s most acclaimed release features the best in samurai movies combined with a great plot and very intense acting, mainly from Tatsuya Nakadai. Nakadai isn’t often the bad guy, but contrary to most samurai or jidaigeki movies, the main character in this movie is the bad guy and Nakadai excels in his performance, I’d risk saying it’s his greatest performance along with his performance in The Human Condition Trilogy.

Ryunosuke Tsukue is a highly skilled swordsman, who has an intense love for killing; Nakadai plays a demented and calmly deranged swordsman who feels a certain degree of pleasure in killing others and only trusts his own sword. The movie spans a three year period from 1860 to 1863. Tsukue’s intenseful and remorseless acts come back to bite him. His actions in both the past and present, killing his avengers, have dangerous consequences in his mind, altering his entire spirit and making him even more dangerous.

That change is actually brilliantly executed by Nakadai’s powerful acting but also by a very well designed storyline, which maintains Tsukue’s past actions fresh in the viewer’s mind, while maintaining a great follow-up to Tsukue past actions in later years. The movie evolves into a snowball creating gruesome expected consequences to Tsukue’s life and his entire spirit. This movie has no proper ending; it might have one if you want to interpret it, but there is no actual ending. “The Sword of Doom” was supposed to be the first of a series of movies that weren’t actually made.

Another very interesting movie left off the list was “Japan’s Longest Day” (1967), also by Okamoto; it’s a very factual account of the last hours of Japan in the Second World War, and a star-studded movie with the best actors in Japanese cinema.

13. Like Father, Like Son (Hirokazu Koreeda, 2013)

It mixes strange feelings and emotions, both positive and negative, as it may be considered one of Koreeda’s best “polished” movies with a difficult storyline due to the degree of emotional reach the movie may have on its viewer. It does contain a happy encounter of sentimental reception due to its end, and the confirmation of the love between father and son, but also has its tragic perspective of the dubious feelings the father has for his son. I called it “polished” due to the aggressiveness of feelings it may cause the viewer. It is Koreeda’s confirmation as one of the best or the best Japanese director of the last 20 years.

It tells the story of Ryota Nonomiya, a businessman who lives for his work. He and his wife discover that their son isn’t their biological son and was traded for the son of another family. The father and wife have to face this situation and try to accept their biological son into their family, essentially “trading sons” with the other family. Although it was a shocking thing to do, Koreeda does try to understand how a family could react in such a dramatic case, clearly mixing sweet and happy emotions with very tragic ones.

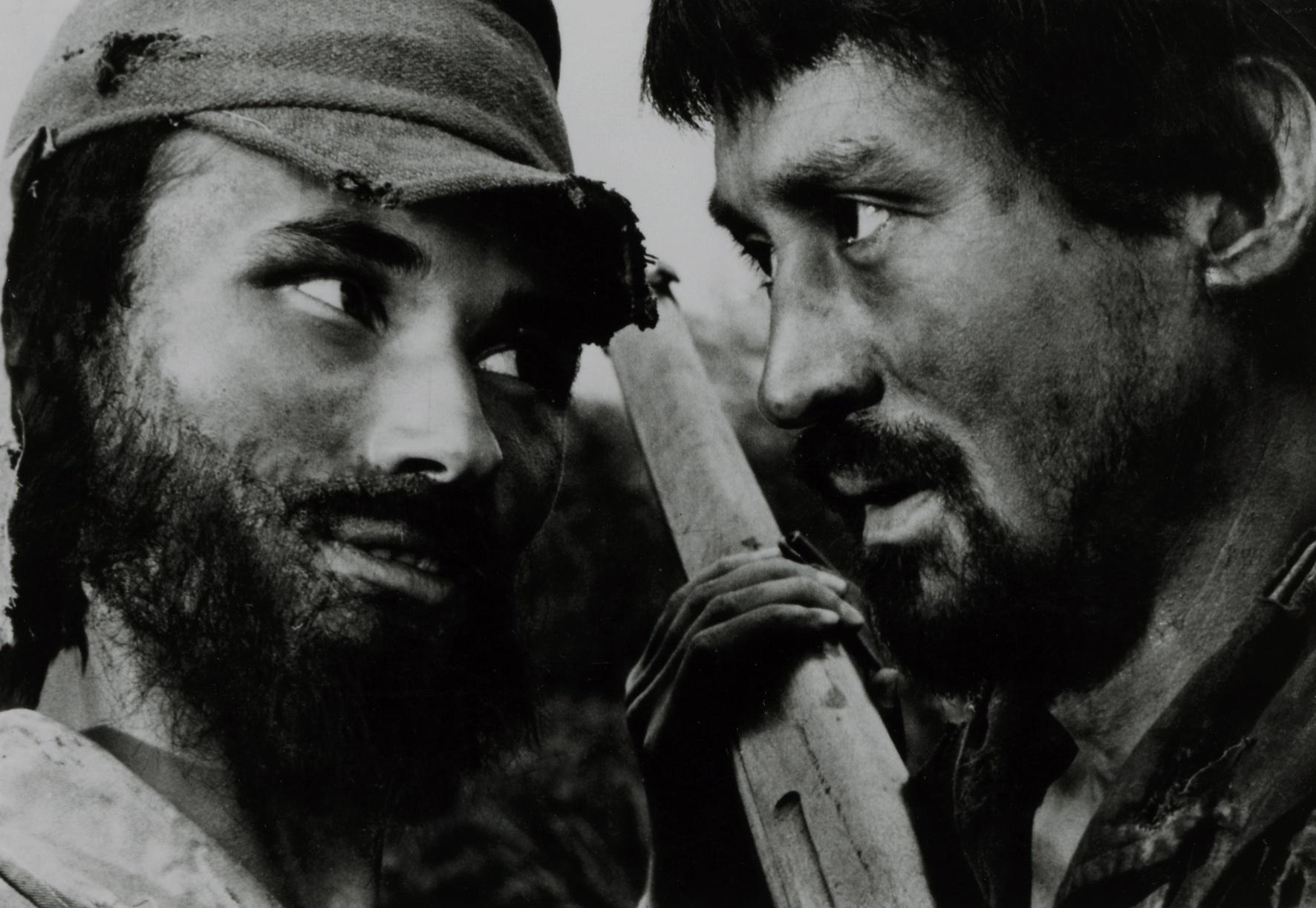

12. Fires on the Plain (Kon Ichikawa, 1959)

Ichikawa’s style certainly differs from most of the Japanese masters, containing a mix of sordidness, darkness and human cruelty with a feeling of hope and humanity. “Fires on the Plaini” is one of his greatest releases alongside “The Burmese Harp”, as it features the shreds of every single emotion mentioned above. It follows the path of a Japanese soldier with TB in the final months of the Second World War, with the Americans closing in on Japanese grounds. That soldier has to stay alive and partners with several other Japanese soldiers.

It gives us the sensation that the soldier enters a new low psychologically with the advance of the war. It shows a completely gruesome and visceral account of the battle, realistically but also in the darkest way possible, confronting the viewer with the worst inner-self of a human being. The movie, at the time, wasn’t well received due to its brutality and elements of repulsiveness.

A critic once said, “Ichikawa is a cinematic entomologist because he studies, dissects and manipulates his human characters”, and he is completely right. Much like “The Burmese Harp”, “Fires on the Plain” presents a darker side of the war and human emotions, while “The Burmese Harp” shows us a much “brighter”, emotional and sentimental side of human emotions.

11. Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969)

It’s considered an essential work of the Japanese New Wave that rose in late 50s and early 60s. “Funeral Parade of Roses” mixes experimentalism and some forms of documentary style of filming. It hugely influenced the works of Stanley Kubrick, mainly with respect to his greatest masterpiece, “A Clockwork Orange”.

The movie is greatly enhanced by its very powerful visual content and graphic scenes that even for today standards would be considered as raw and way too graphic for the normal cinema showings, and can definitely be classified as rated M or X. It goes back and forth as the normal life of transvestites and the sub-scene emerged in Japan of the late 60s. For that reason, the movie is very often associated with the gay community in Japan, but also as one of most controversial works of Japanese industry. It’s by far the most controversial and graphic movie on this list.

Eddie is a transvestite who works for a gay bar and is its major “attraction”. The movie is filmed in parts as a documentary as it follows the lives of Eddie and other transvestites who are desired by the normal Japanese businessman and other men looking for pleasure. It goes back and forth, with the beginning being almost the end of the story, containing flashbacks of Eddie’s life and showing some of his dark and obscure past. The ending surprised me with an unexpected twist to a very polemic and controversial movie that hadn’t any fear to be even more graphic and controversial in this ending.