4. What silent films teach us about the use of silence and music (and surprisingly dialogue)

It’s customary to take silent films as features and short films accompanied by a gay music or music with an exaggerated melodramatic tone. Although it was during the silent era that music for film grew and set for itself different tones in order to accompany the different film genres, there are films that during this era make an extraordinary use of silence.

As filmmakers decided to invest in cinematography, creating iconic images some also dedicated themselves into exploring the importance of sound and silence within film, particularly by using silence in moments after a great climax or moments when a character discovers the truth or struggles to deal with the truth in some given situation.

Some pieces of silent Japanese cinema explore exactly the role of silence in film, particularly in family dramas, which is a characteristic that was kept throughout the decades into the transition to sound film and so forth. Later filmmakers whose works display this characteristic are Yasujirō Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi or Mikio Naruse (among many others).

However, some of the most known films of this time to make a great use of the contrast sound/silence are Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” (1928) and “Vampyr” (1932), as well as, “The Man Who Laughs” (1928) directed by Paul Leni or “The Wind” (1928) directed by Victor Sjöström.

By investing in new ways of storytelling through the complexification of the mise-en-scène, through sound and its omission, a great number of filmmakers also discarded “dialogue” or intertitles. Like the example previously accounted of F. W. Murnau, who didn’t want to use intertitles in “Sunrise”, many filmmakers felt that intertitles sometimes worked as cuts to the film’s rhythm or simple didn’t see any necessity for the use of intertitles. Famously, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton “competed” against each other to see which one would use the less number of title cards in their films. Victory went to Chaplin.

Historical facts aside, the valuable lesson to be learn here is that just like an excessive number of scenes when preparing a script or a screen adaption (we don’t have to see everything), one has also to be extremely careful with the use of dialogue because not everything needs to be told by words. All there is to do is to think out of the box and be sure to make a great resourceful use of the different elements within the film (cinematic language). That is called narrative economy.

5. Because silent films are the founding fathers of special effects

Long before the science fiction boom of the 1940s/1950s, in France, George Méliès revealed himself a pioneer in the use and development of special effects in filmmaking. Among his most notable works are the Jules Verne inspired “Trip to the Moon” (1902). However, before this film, Méliès had experimented tricks like sudden disappearances, multiplication of people or parts of the body. Effects achieved through the use of animation, jump cuts, dissolves or superimpositions.

Nevertheless, Méliès shouldn’t be perceived only as a creator of ‘trick films’ because with “Joan of Arc” (1900), the first recorded film adaptation of this story and “Bluebeard” (1901), the filmmaker proved himself capable of telling stories beyond marvelling the audience with visual tricks.

Also noteworthy is the fact that Méliès had his films hand painted in order to achieve higher levels of visual greatness and, of course, success with his audience. Among his works, the most interesting are “The Vanishing Lady” (1896), “The Four Troublesome Heads” (1898), “Joan of Arc” (1901), “Bluebeard” (1901) and “Trip to the Moon” (1902).

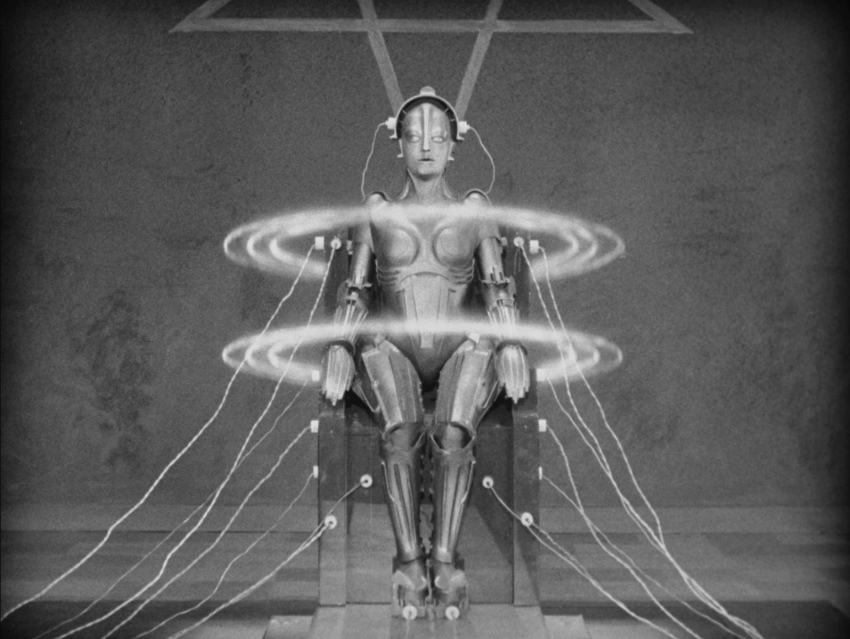

After this initial development during the period of the cinema of attractions, special effects grew exceptionally with the birth of Universal’s first horror films and with the works of German expressionist filmmakers like Fritz Lang who in “Metropolis” (1927) used miniatures and matte paintings (combining details or elements from various images into one).

6. Because Silent films are historical documents

Indeed, silent films are historical documents of cinema’s own advances and of reality itself. Films like “The Immigrant” (1917), “Mother” (1926), “Metropolis” (1927), “October” (1928), “The Crowd” (1928), “Pandora’s box” (1929) among many others carry with them the heavy burden of reality.

Some chose to make observations of society condemning its values and behaviours, others to reflect on its problems, others choose to take an active role in displaying the roughness of life and human condition and others are that simply choose to make an ironical comment on reality itself.

7. Because even today the visual magnificence of silent films still surprises us