5. Provocative Commentary on the American Dream

A film created in and about America by a German filmmaker, “Paris, Texas” was well received in many places globally. Competing with such masterful filmmakers as Lars Von Trier, Satyajit Ray, John Huston, and Werner Herzog, it received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, but ironically, was poorly received in the US.

Wenders attributes the poor American reception to Americans’ unfamiliarity, and thus discomfort, with their story being told by an outsider, unlike in Europe where these boundaries are commonly crossed by filmmakers. “And that’s why it was sacrilege for them,” he explained in an interview. Despite being initially shunned by American audiences, it’s now widely respected by global and American film lovers alike.

The film grapples with the expectation of both the idyllic American family and conventional gender roles and highlights some of the harsh realities that pervade American culture such as alcoholism, domestic violence, and relationship abuse that are often well hidden by the walls of the American home.

Whereas the typical American story would end with the reunion of the family, the harsh truth is that Travis is not yet able to be a secure and supportive provider for his family, and so he must give up this typical masculine role in order to do the right thing and protect them from himself.

At the beginning of the film, he subconsciously attempts to reunite with the family by returning to Paris, Texas, where he intended to build their home, because as he later discovers, attempting to reunite with the family directly causes him to face the harsh reality that he can never really return.

The road movie has become a classic American genre, and is often used subversively to glorify the outsider and provoke Americans to question their values.

Such films as “Bonnie and Clyde”, “Badlands”, “Thelma and Louise”, and “Easy Rider” use the road to identify the characters as anti-heros, fringe characters, and outlaws, challenging the American Dream, and denouncing the iconic American domestic life. “Paris, Texas”, whose protagonist neither belongs to the American household nor seeks to subvert it, belongs to this canon while simultaneously departing from it.

6. Gorgeous Location and Cinematography

One of the most memorable aspect of “Paris, Texas” is the incredible landscape and scenery. Wenders has said that the original concept was built around the opening scene: a man walking alone in the beautiful and desolate West Texas desert.

The titular town of the film always remains a distant dream, but the film takes full advantage of the majestic canyons of Big Bend and Terlingua in West Texas, the haunting Mojave desert in California, and the glistening cityscape of LA. Although Wenders denies the inspiration, the film is reminiscent of the classic Westerns of John Ford, and is often compared to “The Searchers”, which has some similar plot motifs.

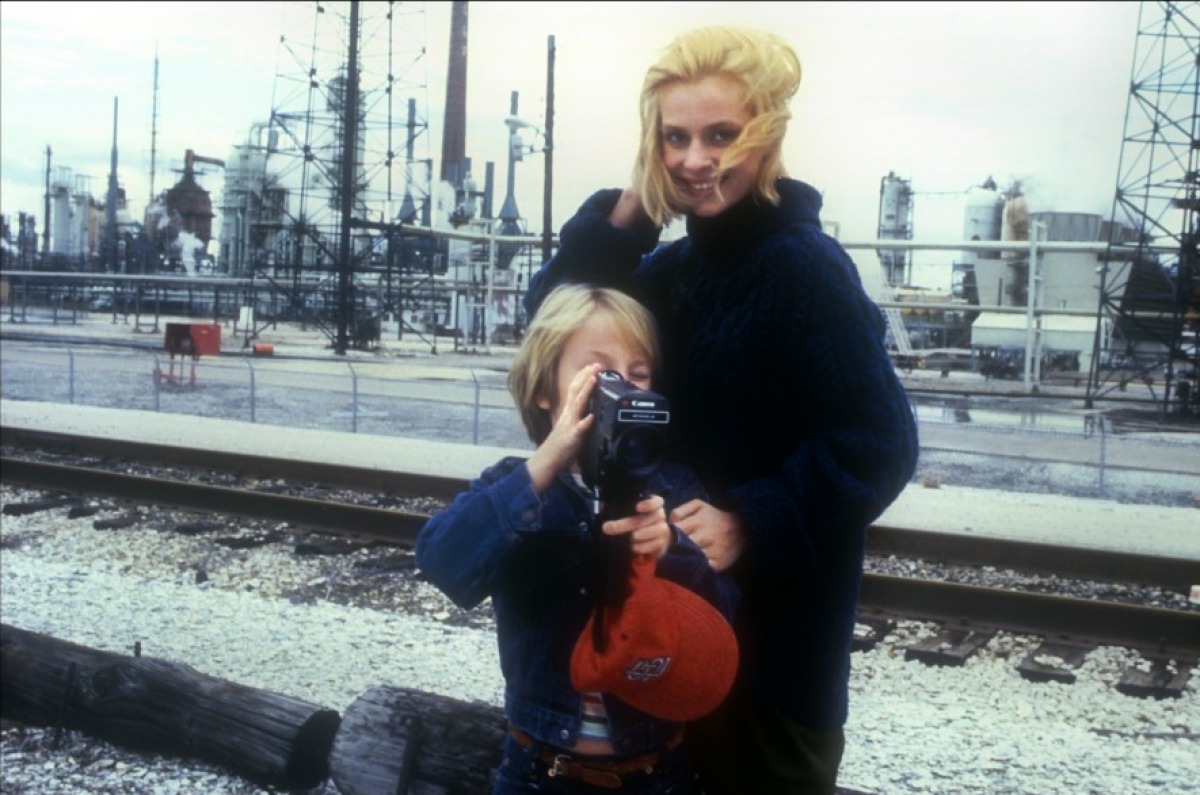

The film has a consistent color palette throughout of the limey green of neon lights, a subdued sky blue, and an ever-present pop of red that appears in nearly every single shot in the form of hats, furniture, shirts, bedspreads, more neon lights, etc… But despite this pervasive color theme, since the film follows the aesthetic of the organic American landscape from the start, it does not appear overly intentional or stylized.

The aesthetic of the interiors is designed after what is already present in the landscape. The cinematographer, Robby Müller, had worked with Wenders on many films, in addition to several early films by director Lars Von Trier and films by director Jim Jarmusch.

Robby Müller’s work, and by default Wenders’, especially early on, was either black and white, or if colored, then muted and gritty, so bright pops of color, stark lighting, and harsh neons were somewhat atypical, but they are used masterfully in “Paris, Texas”. To both Wenders and Müller, color is not the default option; it is an intentional choice, so it makes sense that it is handled here with special care and consideration.

7. Artful Screenplay

It’s not what the characters say in “Paris, Texas” that makes the screenplay so great. It’s what they don’t say and how the story is shown to us rather than told.

For example, the protagonist barely speaks for the first half of the film. We see Travis and his son bond largely through actions and not words and the home movies that inform us about the past are silent, yet we know what each character is thinking and feeling without the need for constant exposition, which makes those moments when things are spoken directly all the more poignant.

Like a great scary movie that doesn’t have to show the monster for us to feel that it’s terrifying, it shows just enough of Travis’ jealousy for the events of the past to be accessible to our imaginations without the need for a melodramatic flashback.

Again, like many other aspects of the film, the screenplay is totally unpretentious. Even the pièce de résistance of the script, the famous monologue scene, doesn’t sound overly prepared. Particularly Jane’s speech is so beautifully pointless and genuinely seems off-the-cuff. She wants so badly to express to Travis how she feels, yet has no conclusions and no answers, which only serves to show us, and Travis, how devastating it would be if he were to return to her life without having first confronted his inner demons, justifying his ultimate decision.

The screenplay was essentially written by three people: Wenders, who had more to do with concept than script, Sam Shepard, a highly acclaimed and innovative American playwright, and Kit Carson, a lesser known actor and screenwriter who stepped in in Shepard’s absence.

As Wenders describes it, when Shepard and he decided to make a film together, Shepard criticized him for having scripts that were “always meandering” and proclaimed that “Paris, Texas” would have “no detours”. “Paris, Texas”, although following the conventional Hero’s Journey, twists and turns in interesting directions and oftentimes violates the expectations of the viewer as well as ending unconventionally, but it avoids detours in the sense that it is told concisely, with every moment and every scene contributing to the main storyline.

8. Ry Cooder’s Soundtrack

Ry Cooder, who created the score for “Paris, Texas” is often recognized as one of America’s greatest guitarists, specifically known for his use of slide guitar, which he employs in his score to soulful and intense effect. Like Wim Wenders’ direction, and many other aspects of the film, the score is raw and unencumbered by distracting over-production.

Primarily featuring the solo slide guitar, it is purely there to support and enhance what is already happening on screen, and like the screenplay, uses omission and silence as a valuable tool. Not only does the soundtrack mimic the style of the film in it’s artistic subtlety, but it contains sounds that are classically American, borrowing from a song called “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” which was written by the classic American gospel and blues musician Blind Willie Johnson, blending with the landscape to create an atmosphere that is unmistakably American.

Wenders, in a later interview, spoke about Cooder’s work with great admiration, saying it may have been the most influential part of the film on the art world, alluding to several bands that formed soon after the film’s release that used elements of the film in their names. Wenders and Cooder would continue their collaboration with the award-winning Buena Vista Social Club documentary.

Author Bio: Tori Galatro is a freelance writer and film junkie living in Austin, Texas who wants to write about film, art, and culture for you. You can find her work and contact info at torigalatro.com.