5. Wanderlust

Herzog has often spoken of his own wanderlust. He is probably the only director to have made a film on all seven continents. He views the exchange and understanding of views when in a foreign land as crucial to experiencing life fully. Ironically, to be stuck inside a cinema appears to be anathema for a man like him. On contemplating his own film school, he said “if I did start one up you would only be allowed to fill out an application form after you have walked alone on foot, let’s say from Madrid to Kiev.”

The people in his films too appear to be afflicted with an inability to stay in one place. To stay still is to invite death, or at the very least a deterioration of the mind, as it does so for the titular character in Woyzeck (1979), again played by Klaus Kinski, a soldier broken down by a manipulative doctor, an authoritarian military commander, and an unfaithful wife until he is driven insane.

The protagonist in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Stroszek, both played by Bruno Schleinstein, is in both cases a man who is unbound by the traditional constraints of society, a man who simply has to speak what he feels to speak the truth. He is an innocent, more positive version of the failed Nietzschean obsessive discussed earlier, but he too is afflicted by wanderlust.

Kasper Hauser in the former film was a real-life figure who appeared one day in Nuremburg in the 19th century, unable to speak and holding only a letter in his hand which explained that he had spent his entire life in a prison cell. In Herzog’s again rather fictionalised recreation, Kasper Hauser becomes a man who increasingly feels restrained by the surrounding rules of the petty bourgeois society that takes him in, and desires more and more to transcend and leave that land.

In Stroszek, Schleinstein plays a very similar character – he was in real life, a mentally troubled man who had been in and out of mental institutions and prisons for much of his life, with no previous acting experience – and again, due to being unable to ‘fit in’ in his native Germany, this Bruno emigrates to the US, only to find more dilapidation and just as many constraints.

Herzog’s characters desire freedom, and go to the ends of the earth to find it, yet they seem unable to track it down. It is always just out of reach, just beyond the horizon, an endlessly setting sun that refuses to slip away, yet always drawing people towards its light.

6. Failure of rationalism

Leading on from this wanderlust, there is in Herzog’s work a frequent recurrence of a failure of rationalism. The sense that one of the central concepts of the European Enlightenment, that with argument, persuasion, logic, and rational thinking, humanity is able to overcome its issues, is rarely successful in Herzog’s films.

Bruno Schleinstein’s characters attempt to rationalise the confusion and constraints that occur all around them. In both films his rationalisation leads to tragedy, for his rational thinking is not always the rational thinking of those around him. He is incapable of aligning his thinking with those around him, leading only to sadness and frustration.

In Heart of Glass (1976), one of Herzog’s strangest films wherein most of the cast were hypnotised during filming, a town becomes increasingly fearful for its existence after a famed glass-maker dies, taking the secrets of his method with him and in turn the town’s financial security. They grow gradually insane and violent in frustration, rational thinking again giving way to fear and shock.

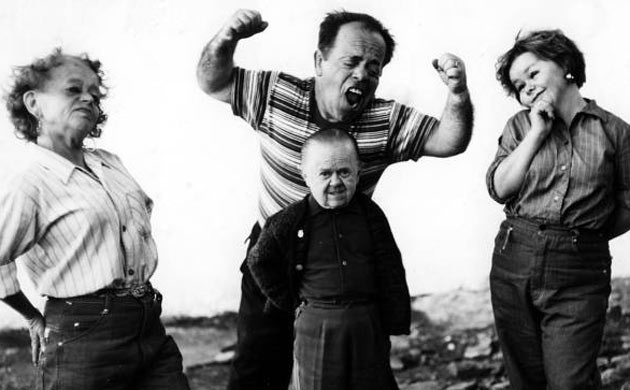

Mystical forces overwhelm European civilisation in Nosferatu, just as nature did so in Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, and Grizzly Man. Herzog states this most pointedly in one of his earliest feature films, the wonderful and underrated Even Dwarfs Started Small (1971). A group of dwarves in some kind of facility overthrow the ruling sections, who are also dwarves, and proceed to wreak havoc for an hour and a half, going as far as crucifying a monkey and parading the poor thing.

In that film’s hellish vision of humanity, all logic and sense goes out of the window, as people abandon their senses in favour of complete and utter freedom. However, the freedom which they desire is only temporary and nonsensical. Pain is inflicted on innocent creatures, both human and animal, and all concepts of rational thinking cease to exist. Why? There is no why. There just is. Complete freedom to human beings results only in madness, as rationalism takes leave of us. Herzog’s Nietzschean protagonists take leave of their own rationalism in their journeys, and so lose their grounding as sane men.

Looping back to man’s inability to comprehend nature, this inability by humanity to take control of reason is one of Herzog’s most cynical, nihilistic and also deeply refreshing aspects.

What comes through ultimately is a freedom that comes from within itself, a realisation that despite all the horrors on this earth, men and women are still capable of producing the serenity we see in those long-forgotten caves we are shown in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, when they affirm their ability to reason and think creatively without being in hock to ideological functions. In the hands of a lesser director, this failure of rationalism would be a cause for despair. In Herzog’s, it is a liberation in and of itself.

7. A critique (or perhaps an affirmation?) of neo-colonialism

Now we come to arguably the most controversial aspect of Werner Herzog’s cinema. Having filmed in the Amazon on numerous occasions, using scores of local indigenous peoples as extras, and doing similar acts in Africa, he has at times come under criticism for alleged exploitation of the local people. Needless to say, particularly on Fitzcarraldo, conditions for many of the crew were quite bad.

His films too, sometimes seem to teeter between criticising and affirming the crimes of colonialism. Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo both depict failed journeys undertaken by men who ventured into the jungles in an attempt to claim something. In the case of the former, it is a man attempting to claim land and glory for the Spanish empire. In the latter, it is a man looking for riches for himself, so he can bring opera (a very Western form of music) to the midst of the jungle. In the latter, the protagonist succeeds at least partially, giving some voice to his madness and affirming his acts, albeit in a subversive way.

Cobra Verde (1987) is the story of a bandit (Klaus Kinski again, in his final role for Herzog) who is sent to Africa as a punishment for his crimes in Brazil. Finding himself in a Portuguese colonialist outpost and tasked with procuring slaves, the titular character kills the mad native king with the help of a warring tribe and takes charge himself. All three films are stories of colonialist excursions that could quite easily tip over into glorification and affirmation of these crimes.

What matters however, is the respect Herzog affords the indigenous people, at least onscreen. Their beliefs are taken not as a sign that they are ‘lesser’ people, as many European colonialists did, but as a symbol of the fact that they perceive the world differently. Their knowledge, language, and context is different, and Herzog grasps this.

Thus, through his many more anthropological documentaries, from Where the Green Ants Dream (1984, and again a documentary with possibly more fiction than fact), to The Wheel of Time (2003), about Australian Aboriginal and Buddhist practices respectively, there is a respect and curiosity about other cultures that shines through, a curiosity in the way different human beings behave and react to each other.

That this respect onscreen does not always appear to be translated to behind the camera only adds to the contradictions. Whether it was through lack of money (always a constant problem Herzog has battled), or through carelessness, or that very Western trope of not actually caring about the area one is meant to be co-operating with, Herzog has found himself frequently in trouble for the conditions that his crew and extras found themselves in.

During the filming of Fitzcarraldo, a certain section of boat-dragging was apparently given a 30% of succeeding by on-set engineers, with failure endangering the lives of many of the men, many of them indigenous, working on the film. Werner Herzog went ahead anyway, valuing his film over that of the men around him.

Perhaps he is just genuinely insane…

8. Rootless, fatherless characters

When remaking Nosferatu, Werner Herzog was asked by The LA Times why he chose to remake, almost shot-by-shot, F.W. Murnau’s 1922 gothic horror classic. For him it was about “connecting with the generation of the grandfathers, in this case with F.W. Murnau. So for me it was like bridging a void, a big gap in reconnecting to the great cinema of the 1920s.”

Born in wartime, he, like many others of his generation, felt or in many cases actually were fatherless: “since we were the first postwar generation and we had no fathers, we had no mentors, we had no teachers, we had no masters, we were a generation of orphans,” said Herzog in the same interview.

Germany in the 1920s was a tough place. It was still rebuilding after World War I whilst suffering rampant inflation and chronic political instability. Yet it was also one of the most exciting filmmaking countries of the early cinema. German Expressionism was arguably cinema’s first full-blown movement, beginning with Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and following on through F.W. Murnau’s classics and reaching its pinnacle in 1931 with Fritz Lang’s M.

However, when Hitler came to power in 1933, he and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels set about bringing the film industry under their complete control. Many filmmakers fled – indeed, many of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers of the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s were of German or Jewish origin; Billy Wilder, Ernst Lubitsch, Douglas Sirk, Robert Siodmak, and countless others – and the German film industry became exclusively the domain of propaganda or soulless light entertainment.

For Herzog’s generation therefore, there was no immediate national cinema to draw on. His characters, alongside their wanderlust, seem to have no roots, no core, no fathers. There are very few families in Herzog films, and those that do appear often seem to be unhappy or struggling. Invincible (2002) is one of the few portrayals of a content, healthy family in Herzog’s cinema, and that film follows a Jewish family in 1930s Germany, and you don’t need me to tell you how that works out.

Woyzeck, Stroszek, and The Enigma of Kasper Hauser all centre on characters coming from unhappy or completely broken families. The protagonists in Aguirre and The Bad Lieutenant barely come from any normal familial relationships, so utterly without root are their lives.

This idea of a fatherless world would be oft-repeated amongst Herzog’s contemporaries in the New German Cinema. Many of Wim Wenders’ films, from Alice in the Cities (1974), and The American Friend (1977), to Paris, Texas (1984) feature fathers or father figures who are incomplete, lost, or at odds with themselves.

In Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s masterpiece Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), we see an older generation that still seems incapable of comprehending what happened during the ’30s and ’40s in Germany. Of all the recurring themes in Herzog’s work, this one is perhaps his closest connection to the world in which his contemporaries lived.

9. An absurdist and morbidly dark sense of humour

For all his thematic heft and weight, Herzog has also always been one of cinema’s most underrated and humorous comedians. In his documentaries, from My Best Fiend (1999) to Into the Abyss: A Tale of Life, a Tale of Death (2011), via Cave of Forgotten Dreams and Grizzly Man, his narration is an ever-present source of philosophical musings on the imagery before us, poetic connotations, and a dark, bone-dry sense of humour, all enacted in that pleasing, soft Bavarian tone.

The aforementioned documentaries cover topics as dark as the death penalty and as scary as Klaus Kinski, yet always Herzog presents us with a few moments of humour, no matter how utterly morbid, helping to bring levity and lightness to otherwise deeply depressing and dark topics.

In his features too, absurdism abounds of a style that would make the Monty Python crew proud, although it too is nearly always tempered with morbidity. Even Dwarfs Started Small might just be the German master’s most funny film, yet that films angles its laughter back at the audience, reminding us that sometimes we ought to think twice about what we laugh at.

The Bad Lieutenant also brings plenty of absurd moments of dark humour to proceedings, resulting in one of Herzog’s most entertaining films: watching Nic Cage assault old infirm ladies and shout “his soul is still dancing” at a dead man is a madly captivating experience.

This bizarreness results in Herzog’s work always bringing itself back from the brink, ensuring that the near-overwhelming darkness and nihilism of many of his films is brought back to something that the audience can breathe out towards. It’s the secret to all good art – balance, light and shade, moments of madness followed by moments of levity. Such is Werner Herzog’s cinema, and long may it live in the memory of cinephiles everywhere.