2. Manipulation of Space and Time

The medium of film is physical space. Manipulation of space is largely what gives Kaufman’s films their off-kilter cinematic quality. Defamiliarizing space is one of his primary methods of visual estrangement. There is perhaps nothing more familiar to us than space and the objects “in” it.

By rendering the familiar unfamiliar Kaufman interrupts our brains’ automatic processing, making the image jump out at us, kind of like a Picasso cubist painting. He thwarts our brain’s preprogrammed tendency to impose familiar patterns, in order to delve into deeper underlying areas. He makes the known unknown in order to make the unknown known.

An opening scene in Synecdoche, New York indicates that it is three different days, on a newspaper and a milk carton, within the span of about two minutes. Chronology doesn’t matter. Kaufman also shuffles up the order of time in Eternal Sunshine, playing Joel’s memories in reverse.

Caden’s last name in Synecdoche, New York is Cotard. Cotard’s Syndrome is a neurological condition in which a person thinks he is already dead. The name Capgras also appears on an elevator listing. Capgras Syndrome is a neurological condition in which one believes that familiar people have been replaced with exact replicas.

Both of these play heavily in the film. Kaufman’s aim in violating the rules of space and time, as in a dream, as well as in dropping certain hints, seems in part to be an attempt to emphasize that this is a work of art and should be approached as such. Trying to figure out what is “really happening” is about as useful as trying to figure out what is really happening in a dream.

In this regard, Kaufman methods of visual estrangement are reminiscent of the “alienation effect” pioneered by the theatre of Bertolt Brecht. In Brecht’s Mother Courage the actors speak directly to the audience, in an effort to make them realize that they are watching a play, reacting thoughtfully instead of seeking emotional identification and escapist entertainment. Kaufman, too, never ceases to emphasize in his films that this is a fictional universe. He rejects any and all pretenses to realism.

In Synecdoche, New York Caden watches cartoon versions of himself in pharmaceutical commercials, and Hazel purchases a house that is perpetually on fire. Gondry does a good job of producing this effect in Eternal Sunshine through a mix of special effects and skewed sizes of objects, as in the sequence in which an adult Joel is childishly hiding under the kitchen table in his boyhood home.

Similarly, in Synecdoche, New York Adele (Catherine Keener) etches tiny, as in nearly microscopic, paintings. Caden is concerned with big picture; she with the details. It’s a matter of perspective.

The most prominent case of spatial distortion and disorientation in Kaufman’s films is probably the office in Being John Malkovich, on floor 71/2. We see some of its set construction in Adaptation, with its low ceilings, built, legend has it, to accommodate a midget. Even before the film starts defying the laws of physics, the unusual nature of the office and the people in it indicate that something is amiss, off, surreal.

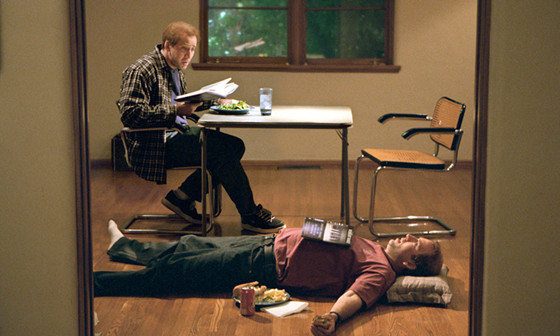

Another good example is when Caden tries to stage the “essence” or entirety of life in a huge, and growing, warehouse complex in which countless scenes are compartmentalized. We also compartmentalize our lives – home, work, friends, family, pets, eating, clothes, etc.

One’s life, and indeed one’s brain, is not a coherent whole. It is compartmentalized, modular. Scattered pieces we continually try to piece together like a puzzle. One’s life resembles the space(s) in which one lives it.

It gives the appearance of a continuous (or contiguous) whole, the “essence” Caden is out to capture, but it is actually fragmented and it is not clear how the fragments fit together. On this view, art may be an attempt to render one’s life whole, frustrating as that attempt may be, as in the following scene.

In a brilliant manipulation of space, in Synecdoche, New York when Caden declares “this is lie” about scenes in a set of adjoining compartments he has the set crew build a fourth wall.

Although the fourth wall has been broken almost from the inception of cinema, for instance in the final shot of The Great Train Robbery (1903), to my knowledge it has never been built. If the fourth wall is a window which allows him to artistically “get at something real,” as Caden put it moments before, Kaufman literally – that is, spatially – walls off this possibility.

Kaufman’s manipulation of space here is another instance of the logic of the absurd. Art should not lie. It should “settle for nothing less than the brutal truth – brutal,” as Caden tells his cast and crew. But all art does is lie, mostly. Kaufman had to invent an imaginary twin to get around this problem. At best art is not a kind of thing that can be true or untrue.

3. Pain

Psychological pain hurts like hell but has no specifically identifiable source, unlike, say, a broken arm. In many respects, it is easier to have broken arm. Arms heal more easily than psychic wounds. Everyone has some kind of psychological pain. Everyone also, to some extent, tries to hide the fact that he or she has psychological pain. That’s why God invented social media: to lie about how happy you are.

Since negative emotions are generally not socially acceptable, they tend to put people off. This happens in Anomalisa when Michael has drinks with ex his in the hotel bar. It is one of those scenes in which you feel uncomfortable for the character, even though it’s a puppet.

Similar to when Kaufman/Nicolas Cage asks the coffee shop waitress to an orchid show in Adaptation. Cage is oozing desperation. The midlife malaise affecting Michaels in Anomalisa is quite palpable as well. It jumps off the screen so much that you can feel it in your bones.

All this, however, pales in comparison to Synecdoche, New York. In this film Kaufman goes out of his way to rub our noses in pain. He runs the gamut from sincerity to sarcasm to melodramatic. It is Frank Capra in reverse, almost putting Ingmar Bergmann to shame.

In several scenes he appears to be mocking artistic attempts to represent pain by turning it into clichéd melodrama. And turning Caden into a modern day Job. In one: “My father died. They said his body was riddled with cancer…They said he suffered horribly. That he called out for me…and that he regretted his life. They said it was the longest and saddest death speech any of them had ever heard.”

In another scene, Caden’s daughter is dying from an infected tattoo given to her by his ex-wife’s, and also his daughter’s, lesbian lover. At her hospital bedside, she asks him to ask her for forgiveness for abandoning her to have anal sex with his homosexual lover Eric (he did no such thing).

When he does, she replies in a fit of tears: “no, I cannot.” Then she dies. The scene would be sad if weren’t so funny, instead of other way around. True to form, Caden’s mother is killed in a home invasion and Hazel succumbs to smoke inhalation in her perpetually burning house. Caden is a cachet of misery.

Or consider the “eulogy” delivered by the minister in one of his plays. I quote it at length because it touches on many of the themes discussed here, which I will note.

Everything is more complicated than you think. You only see a tenth of what is true. There are a million little strings attached to every choice you make; you can destroy your life every time you choose. But maybe you won’t know for twenty years. And you may never ever trace it to its source. And you only get one chance to play it out.

Just try and figure out your own divorce. And they say there is no fate, but there is; it’s what you create. And even though the world goes on for eons and eons, you are only here for a fraction of a fraction of a second. Most of your time is spent being dead or not yet born. But while alive, you wait in vain, wasting years, for a phone call or a letter or a look from someone or something to make it alright.

And it never comes or it seems to but it doesn’t really. And so you spend your time in vague regret or vaguer hope that something good will come along. Something to make you feel connected, something to make you feel whole, something to make you feel loved.

And the truth is I feel so angry, and the truth is I feel so fucking sad, and the truth is I’ve felt so fucking hurt for so fucking long and for just as long I’ve been pretending I’m okay, just to get along, just for, I don’t know why, maybe because no one wants to hear about my misery, because they have their own. Well, fuck everybody. Amen.

What if, as the quote intimates, your worst fears are realized? You have one-way ticket on a last chance ride, and you blew it, by spending your life hoping in vain. Hiding your sadness, hurt, and anger.

Living life behind a thin disguise. Is that a wasted life? Don’t we all do this to some degree? Obviously Caden is an exaggeration. Kaufman, one could argue, blows the issue absurdly out of proportion to extract a grain of truth about our common humanity. Remember, everyone is everyone.

Kaufman’s general message about psychic pain seems to be that art can name the wound, but cannot heal it. The ending of Anomalisa drives this home. Regardless of how many times you reach that state of blissful forgetfulness in trying to drink, drug, or sex it away, it will still be there waiting for you. And for better or worse you will have to deal with it – to adapt, perhaps shamefully – or it will deal with you. This is not say that life is pain.

It is to say, almost platitudinously, that pain is part of life. It goes without saying that art is also a way of dealing with pain, or at least understanding why one is feeling it. But knowing is not enough.

Given that there is usually a method to Kaufman’s madness, his other general message could be that no matter how far art goes, into the realm of absurd hyperbole or elsewhere, there is still an element of human pain which eludes artistic representation, just as it eluded Caden until the very end, though he searched desperately for it.

It is something more than the hackneyed “you can’t feel what I’m feeling.” Something that cannot be boxed in by artistic form.

I think this argument has merit, but an implication of it is, fittingly, that it causes the logic of the absurd to rear its ugly head again. How do you know that you cannot find something – “this a lie” – when you don’t know what you are looking for? And how will you recognize it if you do see it? The situation bears a resemblance to what Supreme Justice Potter Stewart wrote about pornography: ‘I can’t define pornography, but I know it when I see it.’