The Comedy style of Buster Keaton

Buster Keaton was born in the vaudeville atmosphere. His father owned the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company, a small travelling show, where Keaton began performing at the age of three.

Legend has it that it was Harry Houdini the responsible for nicknaming Keaton when he witnessed Keaton’s father throwing him across the stage. Once the boy fell, Houdini said to Keaton’s father “That’s some buster your baby took” and in reply Joe Keaton stated “Well, Buster, looks like Uncle Harry has named you”.

Buster spent all his childhood and teenage years travelling around the country performing alongside his parents. And once the family number ended, in Keaton’s early twenties, he sought work with other travelling shows and once in New York, he became acquainted with Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle – who at the time was working for Joseph M. Schenck – and asked him for work. They worked together on several short films and when Schenck’s company relocated in California, Keaton followed and there Schenck allowed him to have his own production unit where he was given full artistic control of his pictures.

In his unit, Keaton worked on various projects such as “One Week” (1920), “The Play House (1921) or “The Electric House” (1922). However, due to the decline of interest for ‘two rellers’, Schenck asked Keaton to work on feature films which lead to the release of the following: “Three Ages” and “Our Hospitality” in 1923, “The Navigator” (1924), “Seven Chances” and “Go West” in 1925, “The General” (1926) among others.

Despite his success among his peers, among audiences and critics opinions always remained mixed and due to the high cost of his productions and little return, his distributor – United Artists – insisted on putting a restrain over his artistic control which it did during the productions of “College” (1927) and “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” (1928).

Keaton, unsatisfied with this loss of control decided to sign with MGM in 1929. An event that marked the beginning of the end of his career for once in MGM Keaton was not permitted the extent of improvisation and freedom he had had before. From then on, his career fell apart and he found work occasionally in vaudeville, obscure film productions, and later on TV.

Funny thing, before moving to MGM, Keaton was advised by Chaplin not to make the move because, as Chaplin predicted, they would take his freedom away.

1. The use of Slapstick elements

Keaton’s filmmaking style was in almost every aspect different from Chaplin’s. In his encounter with Arbuckle in New York, Keaton borrowed a camera from him and took it to his room, where he disassembled and reassembled it in order to understand how film worked. As insignificant as this little story may seem, it actually divides a clear line between Chaplin and Keaton and the elements they put more emphasis on.

Buster had no interest in exploring the depth or the emotional message than film could incorporate, as a matter of fact, his films are quite simple in that aspect because Buster’s characters are frequently looking to impress the girl they love (“Cameraman” or “Battling Butler”), get her love back (“The General”) or save her (“Go West” – the girl here is brown eyes, the cow) and in doing so get caught up in different misadventures. Where he frequently made use of Mack Sennett’s concept of the “Keystone Cops” – a large number of ignorant policemen that fail in their duties, thus, being a source of comedy.

In addition to this, Keaton made an intelligent use of classic slapstick elements, specifically, falling and being part of a chase. However, there is a distinctive mark in all his films: loneliness.

In fact, as Chaplin gathers allies like the kid (played by a young Jackie Coogan) or Big Jim in “The Gold Rush”. Keaton’s characters frequently enter difficult situations alone, for instance, in chase scenes like in “Seven Chances” (1925), in the journey of “The General” (1926) or set against weather calamities in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” (1928).

2. The physicality of Keaton’s films

One of the most cherished aspects of Keaton’s career is the way he mastered movement. Either body motion and that of visual objects. And this notion lead him to create astonishing sequences where he combined the two – body and object movement – or invested greatly in object movement rather than body movement.

Examples of this are, for instance, the sequences on “The Navigator” (1924) where Keaton sits on the boat’s moving stern wheel or in “The General” (1926) where he sits on a moving train’s bogie. In doing so, he concentrates his comedy not so much on content but on form as well.

In his films, Keaton performed highly dangerous stunts and refused to rehearse them. An example of this happens in “One Week” (1920) where a wall of a pre-fabricated house falls over Keaton’s character.

Another noteworthy element is the famous “dead pan face” for which Keaton became ultimately known. And the “secret” behind this feature is that when Buster was a boy whenever he got thrown away and immediately got up waving at the audience with a big smile on his face they would not laugh, in fact, they sometimes they got Keaton’s parents in trouble with the authorities by denouncing their cruelty towards their child. But whenever after the fall the boy got up with a solemn expression on his face, somehow, the audience laugh.

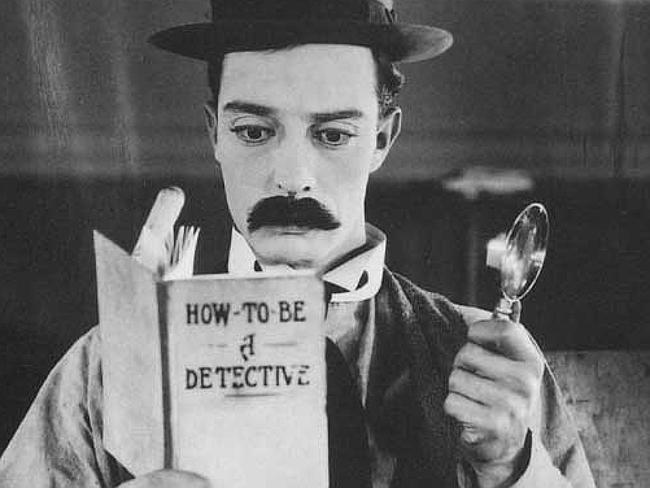

3. Use of Parody

As Chaplin used satire, Keaton made use of parody in his films. And this goes back to when young Keaton was a vaudeville performer. His numbers, particularly those made with his family involved the imitation of the head of the family – Keaton’s father – as well as, impressions of each other or of other performers. So, naturally, this element remained during the transition from performance/vaudeville to film.

Most notably, Buster Keaton choose to create parodies of melodramatic films of his time, such as the westerns made by Thomas Ince and William S. Hart which are parodied in “The Frozen North” (1922), a film in which Buster also ‘jokes’ Erich von Stroheim by dressing like his character in “Foolish Wives” (1922). Despite these examples, his most ambitious parody remains “Three Ages” (1923) which is a parody of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916).

4. Emphasis on visuals

Visually speaking, Buster Keaton reveals a certain closeness to two notions: absurdity and surrealism. This again has its roots in his family’s vaudeville numbers where Buster, his mother, brother and sister would dress and wear makeup to represent doubles of his father.

And this, numeric exaggeration, is something Buster repeats on his film, for instance, in “Seven Chances” (1925) where he is followed by hundreds of brides, in “Cops” (1922) or in “Go West” (1925) where he is followed by cattle across the Los Angeles streets.

Absurdity and surrealism are achieved precisely by the emphasis put on visuals. Keaton defended that comedy should be achieved without being ridiculous and therefore he placed an extreme importance in following the dramatic logic of his narratives and used gags as a mean of progress.

For instance, in “The Navigator” (1924), the underwater sequences triggers, even today, not disbelief but amazement because these gags are justified by providing us with progress and new information – some danger the character hasn’t foreseen, an adversary planning revenge, etc.

And for this reason, unlike Chaplin, Keaton uses editing to achieve precision and more than that a cohesion between narrative and gag.

5. Production methods

As Chaplin, Keaton’s production system evolved being in control of an independent production with high costs and extended schedule. Keaton operated with a small team of collaborators that worked on the story before filming and that came in the form of an outline of scenes that would be open to improvisation while shooting.

This close team of collaborators evolved Eddie Cline (director/actor), Clyde Bruckman (writer), Joe Roberts (actor) or Fred Gabourie (art director) which upon the signing with MGM sort of drift apart working in different productions, which was one of the reasons why Keaton’s career took such a fall, he wasn’t allowed to work with his faithful crew members since MGM employed them in different productions to keep them occupied.

At last, Keaton demonstrated preference to shoot on location because this allowed him to improvise with totally unexpected elements. A great example of this happened in “Seven Chances” where during the chase sequence Keaton stumbled across a small rock and it started to roll down and thus, following him too.

On preview, before the audience’s good response to this particular detail, Keaton decided to go back and reshoot this sequence building larger rocks (with paper and chicken wire) to ‘chase’ him as well.

For more information on this subject, “Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow” (1987) is a great source.

So, who was the best?

Well, as in mathematics, we cannot compare incomparable values or different units of measure, just like we cannot and should not compare the comedy styles of Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

The difference between them is just immense. And, despite the fact that, both improvised, Chaplin favoured sentimentality and Keaton didn’t, both worked independently and so on… these are just circumstantial facts that one shouldn’t use to distance them and see which one is better but instead use these facts to conclude that both were pioneers in understanding the potential of film.

As a line that unites logic and fantasy – to Keaton. As a line that unites the real and the unreal – to Chaplin. We should perceive both for their contributions to comedy, to film and ultimately to ourselves, as we watch them and learn.