The artificial woman is a familiar trope in film. At its most crude, it can serve as a device by which the artificial woman is denied a backstory and is only capable of being viewed through the prism of the male lead’s desires and ambitions. Nonetheless, better entries in this milieu can present profound questions about gender, technology and romantic desire.

At their worst, films in the milieu use the trope of the artificial woman as a crass narrative device to provide the male lead with a passive sex partner. At its most simplistic, this trope represents the primal male fantasy of a woman reduced to a literal sex object.

Artificial women have served as temptresses and traps in myths, legends and fiction as well as in film. They are often constructed to either reinforce or critique a misogynistic worldview in which all female emotion and compassion is seen as false and designed to manipulate men.

Although male robots and other artificial intelligence units are common in film, they generally function as servants, bodyguards or unfeelingly killing machines and are devoid of sexuality. This bifurcation of gender roles reduces both genders to their primal, supposedly primary functions – men as warriors and women as sex objects.

While the robotic woman, or “fembot”, is perhaps the best-known archetype of the artificial woman in film, this list surveys everything from revivified corpses to animal-human hybrids to literary creations. Nonetheless, a number of character traits recur throughout these films.

Unsurprisingly, the trope of the artificial woman in film, posing as it does profound questions about gender, posthumanism and anxiety over technology, has proved fertile ground for academic criticism. Donna Haraway’s influential 1985 A Cyborg Manifesto has served as a blueprint for later critiques.

In her , Haraway discusses cyborgs in terms of breaking traditional binaries between machine and organism, human and animal, physical and non-physical, and so on. She notes that cyborgs break down the boundaries between humans and machines, and therefore reflect our anxieties about the direction of technology and the potential obsolescence of humans.

The persistent presence of fembots and other artificial women in Western culture from Ancient Greece to today has led academic critics to reach for cultural reference points when writing about them. The most prominent cultural touchstone is the Pygmalion myth, popularized by the Roman poet Ovid in his epic poem Metamorphoses.

In the myth, the sculptor Pygmalion creates a statue of the goddess Venus that is so beautiful that he falls in love with it. He is ecstatic when the sculpture transforms into a real woman, Galatea, who he goes on to marry and procreate with. This myth has inspired operas, paintings and perhaps most famously, looser adaptations such as My Fair Lady.

Other cultural reference points alluded to by academics and filmmakers include the Whore of Babylon and the temptress Eve, both originating in the Bible, and other classical myths such as Pandora and her ahem, box that lets out all evil into the world. The trope of the artificial woman can also be found in TV, from the infamous fembots of The Bionic Woman series (later spoofed in Austin Powers) to the sex robot created by the misogynist villain Warren in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

While the Pygmalion myth ends on a positive note, things are rarely so simple in the films discussed here. I want to stress that not all of the films involving artificial women portray these fembots as simple sex objects, and some have presented critical and nuanced takes on this age-old narrative device.

The artificial women portrayed in film are often powerful and complex in their own right, capable of ingenuity and empathy and not just seduction. Their creators, rather than being seen as sympathetically lonely and downtrodden, can also be condemned for their God Complexes that lead them to demand complete control and subservience from their feminized creations. For these psychopathic Dr. Frankensteins, dreams of control and omnipotence often have tragic consequences.

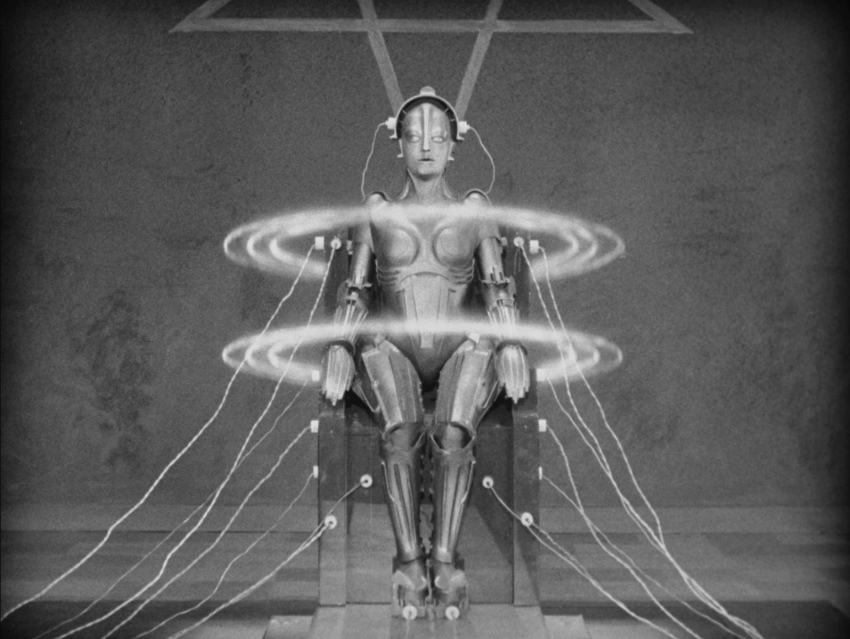

1. Metropolis (1927), dir. Fritz Lang

One of the finest and most influential films of all time, Fritz Lang’s expressionist masterpiece pits a subaltern industrial working class against the ruling elite, who literally live above the working classes in the top floors of the city’s huge skyscrapers, monopolizing the clean air and sunlight. The workers have formed a resistance movement, led by the beautiful and selfless Maria (Brigitte Helm).

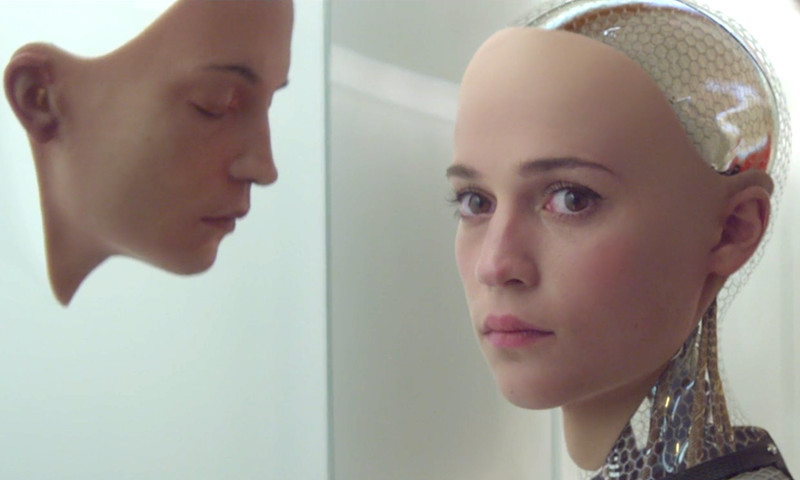

The industrialists approach Dr. Rotwang, who is a fairly transparent homage to Dr. Frankenstein, who is fashioning a female android in the image of his deceased lover Hel. In the intertitles of the 2010 restoration of the film, the machine is referred to as the Maschinenmensch, or literally “machine-human”.

The android embodies what the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw called a “brilliant eroticization and fetishisation of modern technology”, and its iconic appearance suggests both feminine allure and a robotic lack of empathy. At the urging of the Master of Metropolis, the android is transformed into the exact double of the workers’ leader, Maria, but unlike Maria, the android is nihilistic and mindlessly destructive.

In the film’s mesmeric dance scene, Maria’s android doppelganger appears in a glamorous nightclub for the film’s ruling classes, causing them to fight among themselves before she descends to incite the workers to revolt. The dance scene explicitly alludes to the Whore of Babylon, the feminized personification of sin and evil in the Bible.

While the Maschinenmensch has been commissioned to put down the workers’ revolt, the monster escapes from the clutches of its master and becomes hyper-destructive, in a common variation on the Frankenstein story. Frankensteins Monsters often resent their artificiality and take revenge on their creators and the organic world. While the ruling classes expect their robot to be manageable, it escapes their grasp. This is common in films involving artificial women.

2. Bride of Frankenstein (1935), dir. James Whale

Ambivalently received upon its initial release, Bride of Frankenstein is now often considered the finest of the Frankenstein films featuring Boris Karloff. It’s a surprisingly poignant film, following the renewed quest of Frankenstein’s Monster to find his own humanity, and imbues the Monster (played by Karloff) with a degree of complexity that was lacking in the first Frankenstein film.

There is an obvious message to be drawn from the film, and from the Frankenstein films in general. The real villain is of course not the Monster, but rather, the people who persecute him and refuse to see past his frightening exterior. Hoping to find a cure for the Monster’s loneliness, Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) fashions a bride for him.

The Monster shows vulnerability but also hope as he approaches her with his arms outstretched and a timid smile on his face, asking hesitantly – “friend?” The Bride, whose appearance is marked by her distinctive beehive hairdo and streak of white hair, is voiceless, but is horrified by the Monster’s appearance and hisses and screams at him, leading him to declare “she hate me – like others!”

Like in so many films featuring artificial women, the Bride has been created for one purpose, but disappoints her creator. Although the Bride only appears towards the end of the film and is given little agency of her own, she complements this outstanding portrait of alienation and loneliness.

3. The Stepford Wives (1975), dir. Bryan Forbes

“It’s better for us this way…and better for you”. When Joanna, the protagonist of The Stepford Wives, confronts Stepford’s leader about the town’s dark secret for keeping its women subservient and docile, he is unapologetic. Unfortunately, many now remember this film by way of its lackluster 2002 remake, but the original was far more challenging and cerebral.

In the original film, photographer Joanna moves into the pristine suburban community of Stepford with her husband and two children. A shadowy group called the “Stepford Men’s Association,” which Joanna’s husband soon joins, controls everything in Stepford, and women are invariably housewives and excluded from all spheres of public life.

Although Joanna attempts to start a women’s liberation group, to her chagrin the women of the town seem unconcerned with anything apart from cooking and cleaning. The initial reaction from feminists was extremely negative, with director Bryan Forbes noting that he was attacked by a “radical women’s libber” at the premiere, but it has experienced something of a rehabilitation over time.

The community of Stepford has been called a “chauvinist dystopia” and a cautionary tale about a paranoid society where the need to restrain women’s political and personal agency is considered paramount.

As an allegory of men’s anxiety about the rise of second-wave feminism, The Stepford Wives doesn’t strive for subtlety, but its still one of the best cinematic encapsulations of the culture wars of the 1970s. The film’s most arresting image, and the one that’s likely to remain with you, is the sight of Joanna’s unfinished clone, complete with lifeless, beetle-black eyes, a vacuous smile, and a subservient but murderous tendency.

4. Blade Runner (1982), dir. Ridley Scott

This science fiction classic has earned its reputation, seamlessly adapting Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? for film. This film features several different archetypes of robots, which are known as Replicants. Replicants are distinguished by their remarkable strength and intelligence and by their lifeless, black eyes. Nonetheless, as Blade Runner unfolds, the Replicants often prove to be the most human and complex characters in the film.

The film’s most prominent female android is Rachael, who serves as the assistant to Tyrell, the genius creator of the Replicants and a fairly generic Dr. Frankenstein archetype. She is initially unaware that she is a Replicant and requires an unprecedented amount of testing on the fictional Voight-Kampff machine to ascertain this fact.

Although she is introduced as aloof, alluring and unfeeling, she is reduced to tears when she finds out that she is a Replicant and that her memories are implanted and inauthentic. Rachael’s vulnerability and capacity for empathy set her apart from most fembot characters. Harrison Ford’s protagonist, Deckard, treats her like a human, but dismisses her inquiries about his own possible status as a Replicant.

When she asks him why he has never taken the Voight-Kampff test to confirm his own humanity, he simply shrugs. However, it is increasingly evident throughout the film that Deckard has taken on Rachael’s advice and faces a great deal of anxiety about the possibility that he himself is a Replicant.

While Blade Runner offers few obvious lessons about artificial women in film, markers of artificiality are everywhere in the film. Several fight scenes between Deckard and female Replicants take place among mannequins and decommissioned fembots, as though the androids are fighting among the bones of their obsolete ancestors. These scenes serve as prescient reminders of the Replicants’ mortality (they are built with short life spans) and the ephemeral and disposable nature of technology.

While Rachael is a sympathetic character, the film also features two evil Replicants who are built as “basic pleasure models”, Pris (Daryl Hannah) and Zhora Salome (Joanna Cassidy). They are part of the film’s gang of evil Replicants and possess a tendency towards cruelty and malice.

Nonetheless, Pris is revealed as being capable of love and affection for her Replicant lover Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), who has been built as a soldier. The portrayal of these androids as “pleasure models” reflects the usual reduction of male and female androids to their most obvious purposes, with the male robots built as soldiers and the women as mechanical prostitutes.

5. Weird Science (1985), dir. John Hughes

In what is possibly John Hughes’ least-loved film, two horny teenage boys, played by well-known John Hughes regular Anthony Michael Hall and the utterly forgotten Ilan Mitchell-Smith, gain the tools to create a sexy lady Frankenstein (Kelly LeBrock). It’s hardly a sophisticated premise, but at least Kelly LeBrock’s character, Lisa, lacks the passivity of some other fembot characters.

The nerdy protagonists even program Lisa to have genius-level intelligence, “in case they want someone to play chess with”. She ends up teaching the boys about social etiquette and self-esteem and surprisingly, she never has sex with them.

Although the film grows increasingly colourful and absurd as Lisa fights off mutant bikers and turns “asshole specialist” Bill Paxton into a sludge monster, Lisa serves as a constant steadying presence for the boys rather than a monster gone awry.

Weird Science is less sleazy and more willfully dumb that its concept would suggest, and although Lisa has been created as a “dream girl”, she ends up being more of a maternal figure than anything else.

As in Lars and the Real Girl, although this artificial woman lacks a backstory of her own, she serves as the conduit by which the two bumbling teenage leads learn to interact with real women. The film also features Anthony Michael Hall in a lead role and Robert Downey Jr. as a tough guy, just to show you how far we have come since the 1980s.