6. Lars and the Real Girl (2007), dir. Craig Gillespie

In Lars and the Real Girl, a trite but serviceable indie comedy-drama, Ryan Gosling plays against type as Lars, a bumbling, socially uncomfortable loser whose only friend is his brother Gus and Gus’ sympathetic wife Karen. However, Lars’ life changes when he receives a “Real Doll”, (a kind of realistic sex doll) named Bianca in the mail.

While the doll is mute and cannot interact with Gosling or anyone around him, the townspeople slowly come to accept her and value her as a part of the community. Her involvement with the community and acceptance by the townspeople serve as a means for Gosling’s character to mature emotionally, with Gosling attending parties, church and community functions with her.

This riff on the Pygmalion myth sees Bianca’s doll, a static and unfeeling female character, provide the means for Lars’ male protagonist to develop a personality of his own. Ironically, Lars becomes humanized by the presence of an artificial woman with no personality of her own.

Although Bianca is completely passive and mute, she serves as the conduit by which Lars learns to relate to other people around him, especially women. Disappointingly, Lars’ relationship with his Real Doll is chaste, with the filmmakers evidently unwilling to break the taboo of the protagonist actually acting out a sexual relationship with his artificial girlfriend.

Lars and the Real Girl is middling as a comedy, with the townspeople’s shocked reactions to the sight of Bianca serving as its only real joke, but it has value as an unconventional coming-of-age story.

7. Splice (2009), dir. Vincenzo Natali

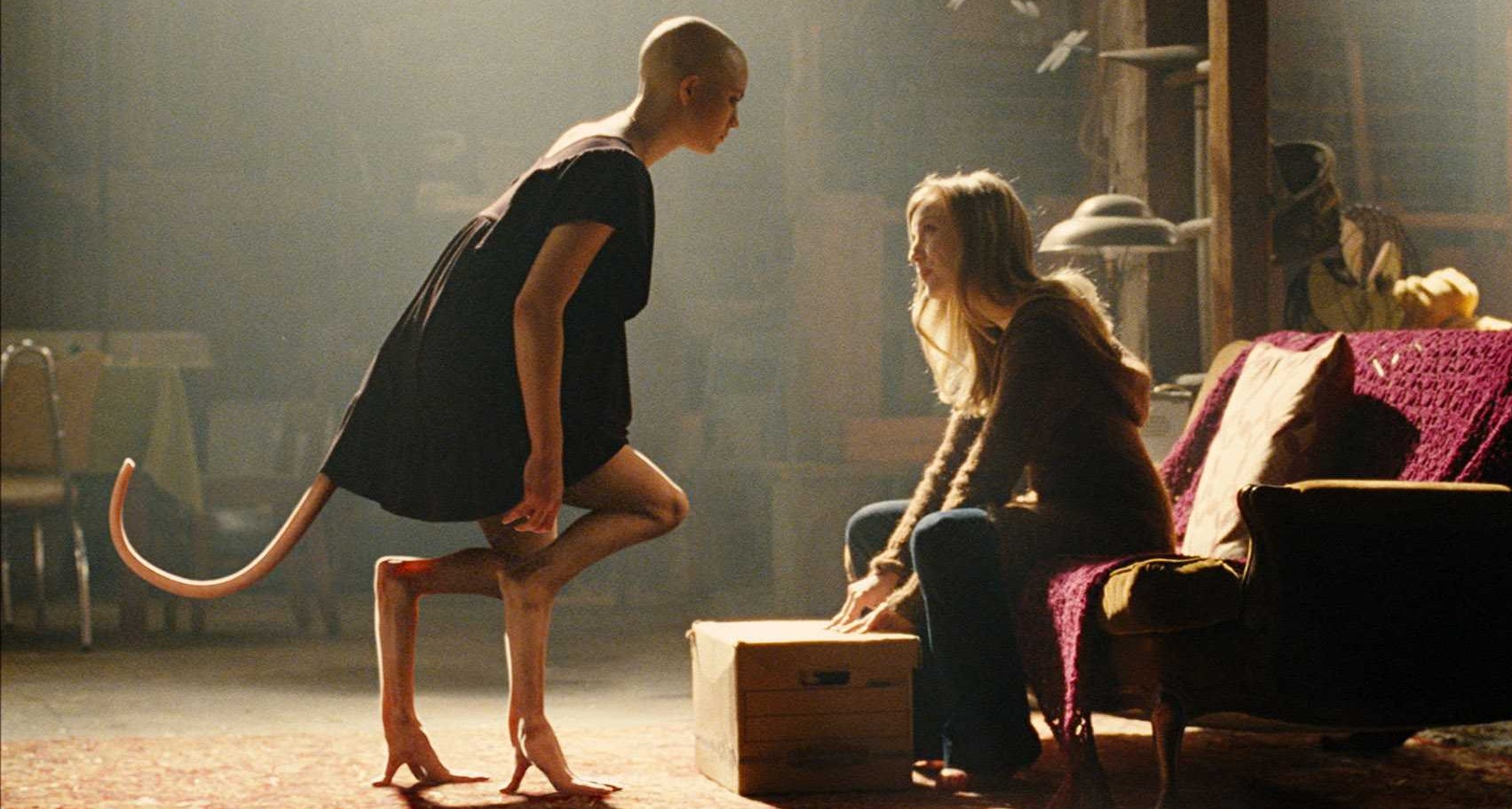

This Cronenberg-esque piece of body horror revels in the grotesque and focuses on anxiety over biotechnology and cloning rather than robotics. This film sees a pair of scientists, Clive (Adrien Brody) and Elsa (Sarah Polley), create a human-animal hybrid that begins to grow at a spectacularly fast rate.

The “specimen”, or Dren (Delphine Chaneac) as she is referred to in the film, becomes a kind of surrogate child for the couple and goes from an object of academic curiosity and parental affection to one of sexual fetishization. While Clive initially maintains a level of emotional distance between himself and Dren, Elsa begins to treat her as a surrogate child.

Once Dren reaches puberty she becomes increasingly feminized, with Elsa applying makeup to Dren while telling her how pretty she is, lamenting that her own mother never let her wear makeup. In another scene, Dren, who is bald, gazes wistfully at a Barbie doll and its long blonde hair while trying on a tiara. She also starts to mature sexually and develops a romantic interest in the male lead, watching Clive and Elsa having sex in one scene before slow dancing with Clive in another.

As with most films about adolescent sexuality, there is inevitably going to be a physical culmination of all this youthful angst. As in most of the films on this list, the loyalty of the monster to its creator does not last for the duration of the film. Similarly to most films where the characters try to play God, the consequences are disastrous and escape the hands of the creator.

When Dren inevitably breaks free from her creators, her motivations are imbued with a desire for both sexual gratification and violent revenge.

8. Ruby Sparks (2012), dir. Jonathon Dayton and Valerie Faris

Zoe Kazan, the daughter of legendary director Elia Kazan, both wrote and starred in this regrettably underrated satire on the self-indulgence of male Hollywood writers.

In Ruby Sparks, Paul Dano’s character Calvin is a romantically and professionally frustrated writer who has recurring dreams about the perfect woman he imagines to be waiting for him. His hackneyed teenage fantasy is fulfilled when he meets a mysterious woman, who appears to be perfect in every way and the only person capable of understanding him.

It later transpires that he has written his perfect woman (played by Kazan) into existence, and that he can continue to write about her and “edit” her to do whatever he pleases. Kazan described Ruby Sparks as a deconstruction of the “manic pixie dream girl” archetype in film, which, similarly to the trope of the artificial woman, reduces female characters to a conduit for the self-realization of the male lead.

In terms of appearance, Ruby (Zoe Kazan) embodies this trope to a tee, with Zooey Deschanel-esque bangs, purple stockings and vintage clothes. Calvin loves Ruby for her unfailing admiration for him and her interest in his favorite pursuits, but becomes frustrated when his dream girl starts to develop her own interests and hobbies.

A moment of truth occurs when Calvin demonstrates to Ruby that she is has been created by his imagination, claiming a kind of existential ascendancy over her. Although this terrific concept could have been taken to far darker and more ambitious places, Ruby Sparks is content to play out as a satire both on the egos of self-important male artists and the writing of female characters in Hollywood in general.

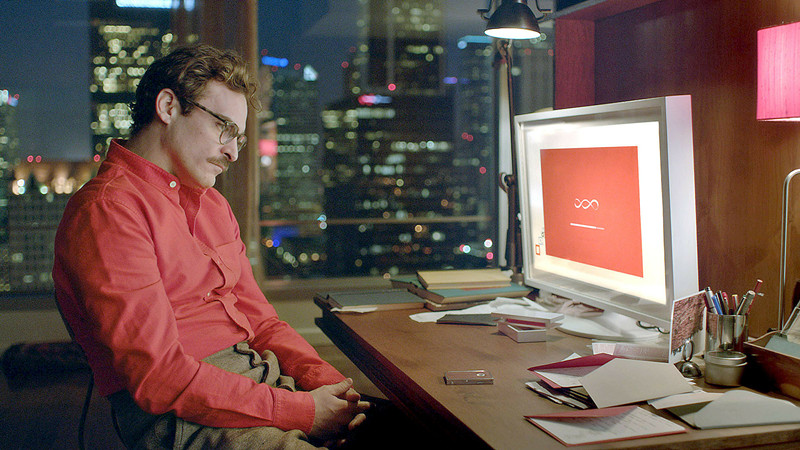

9. Her (2013), dir. Spike Jonze

Spike Jonze directed this satire of the depersonalization of love in the age of Tinder. Lonely Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) begins communicating with an operating system, Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) whom he gives a female voice. Their initially platonic relationship quickly intensifies and as the relationship deepens, Twombly’s avoidance strategies and inability to relate to the real women in his life is laid bare.

Although Twombly believes that his romantic experience is unique, there are of course thousands of people living out their own romantic fantasies with Samantha. During a routine upgrade to Samantha’s software he discovers this and is horrified. Notably, throughout the film it is Samantha, not Twombly, who grows in maturity and sophistication while Twombly flounders and sinks deeper into self-involvement and introversion.

Scarlett Johansson’s character, Samantha, is an inversion of the artificial woman in Lars and the Real Girl. While Lars’ Real Doll is a body with no voice or means of expression, Samantha is a sympathetic voice without a corporeal form, perhaps reflecting Twombly’s anxieties about physical intimacy.

The sophistication of Samantha’s operating system eventually grows beyond what Twombly can provide, making their relationship unsustainable but nonetheless, the film offers hope that Twombly will learn to reconnect with real women, making his involvement with Samantha worthwhile.

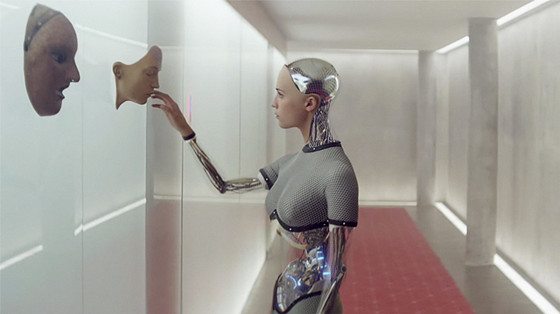

10. Ex Machina (2015), dir. Alex Garland

Ex Machina is a remarkably cerebral science-fiction film that poses deep questions about consciousness, transhumanism and sexuality. Domhnall Gleeson stars as Caleb, a brilliant coder at a multinational corporation, who wins a competition to stay at the retreat of his reclusive boss Nathan Bateman, played with barely restrained menace by Oscar Isaacs. Nathan introduces Caleb to an artificial intelligence unit named “Ava” (Alicia Vikander).

Ava has already passed the Turing Test, demonstrating artificial intelligence, but Caleb’s task is to see whether he can see Ava as possessing consciousness despite knowing that she is artificial. The use of the name “Ava”, a variant of Eve, conjures up suggestions of temptation, manipulation and eventual catastrophe. Ava appears to grow closer to Caleb, and she discusses a hypothetical date with him, even choosing an outfit for herself to distract from her android appearance.

After Ava flirts with him, Caleb asks Nathan why it was necessary to imbue Ava with a sex drive, and whether sexuality is a necessary adjunct to consciousness. A gulf opens between the two men, as Nathan cannot understand why Caleb would have a genuine intellectual interest in this issue. “In answer to your real question,” he says, “yes, she can fuck.” A game of surveillance and manipulation begins to unfold, but it’s hard to determine who is manipulating whom.

Nathan is gradually revealed to be a misogynistic control freak, especially in how he treats his female servant Kyuko. In one visually arresting scene, Caleb discovers the obsolete AI models that Nathan has created, all of them female, lifeless and naked. Caleb has discovered Nathan’s collection of broken dolls.

A mounting sense of dread grows in the claustrophobic confines of Nathan’s compound, and Nathan inevitably comes to face consequences for playing God. Ava’s motives and desires are at least as complex as those of the male characters’, and Ex Machina is an exceptionally dark and challenging addition to the milieu.

It’s a fitting final entry on this list, and shows that films featuring artificial women can depart from cliché and be challenging, cerebral and original.

Author Bio: Alasdair McCallum is a postgraduate student based in Brisbane, Australia. He likes Woody Allen and David Cronenberg, and hopes Andrey Zvyagintsev makes another film soon. In addition to film, his interests include politics, history and travel.