“Cinema is showing more and more. It’s a paranoid, dictatorial cinema. And it’s saying less and less. We need a schizophrenic cinema.”

– René Laloux

And now we wonder where we are

Will there ever be another full-length animated feature quite as wonderfully weird and endlessly imaginative as René Laloux’s underground French classic Fantastic Planet?

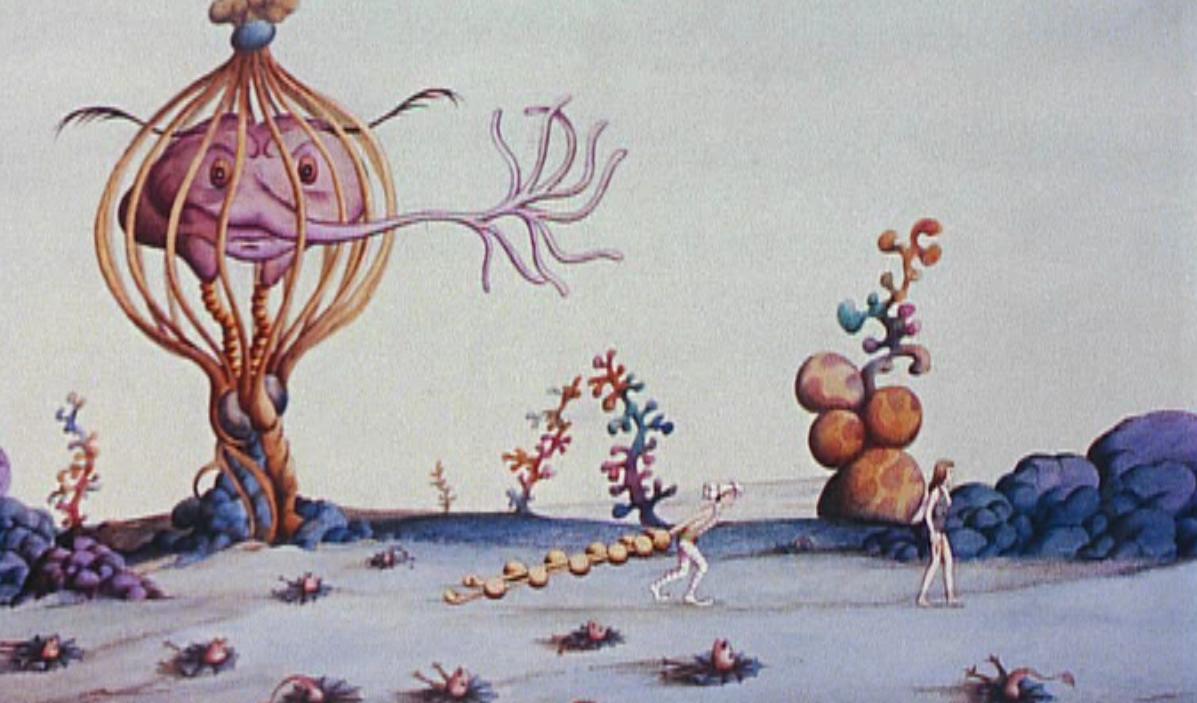

Beset with warm pastel colors and delicate, elaborated illustrations, this allegorical odyssey embraces trippy, psychedelic visuals in an epic of animation. Laloux’s film, which deservedly received the 1973 Cannes Grand Prize, is a winning and welcome cessation from slick, soulless animated marketing vehicles, innumerable imitators and less adventuresome speculative fare.

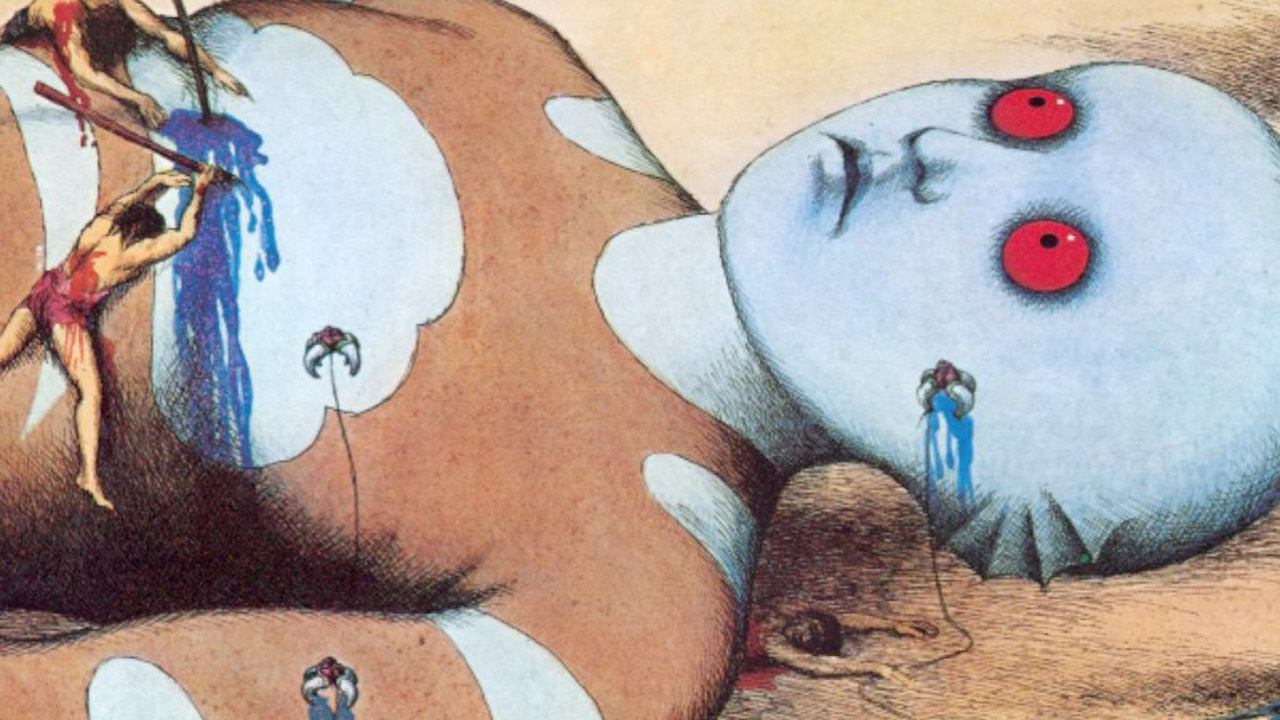

Laloux, working with illustrator Roland Topor (heading an ace team of Czechoslovak animators in Prague), created a singular cosmology reminiscent of the fantastic imagery of Hieronymus Bosch.

Topor draws landscapes and vistas, like the medieval master, that are full of menace and dangerous possibility; duodenal flora, intestinal fauna, womb-like tunnels, frightening phallic and vaginal shapes and simulacrum combined with ancient giant shape-shifting, blue-skinned aliens and antediluvian devils with religious intensity.

Hippie parables and nonconformist cartoons of this sort were produced throughout the 1960s with steadiness but viewed by today’s modern lens, Fantastic Planet retains a bracing, experimental, and variegated viewing experience.

“[Fantastic Planet] is a sci-fi starter drug that turned many a budding fan on to Stanislaw Lem, Tarkovsky flicks, and old-school Heavy Metal comics… It’s not every fancifully encoded cautionary tale that can survive the demise of its historical villains, and it’s not every stoner midnight movie that can stand a second viewing in the sober light of day.”

– Gary Dauphin, Village Voice

Space is the place

Adapted from the 1957 novel by Stefan Wul, “Oms en série” [Oms by the dozen], Fantastic Planet was also influenced and inspired by the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Russians in the late 1960s. On the distant planet Ygam exists a blue-skinned race of enormous, alien beings called Traags.

Traags keep a strangely human-like race, Oms, as pets and playthings. In one of several instances of scathing satire, the Traags treat the Oms with a degree of malice and dogged maternalism, exactly how humanity metes out similar perversion and fetishes to pet cats and dogs.

The Traags also take sadistic pleasure in making the Oms fight one another, often to the death, in matches that eerily echo blood sports like cockfighting and dogfighting. When one of the Oms, Terr, goes AWOL with one of the Traag’s spooky knowledge devices, he soons finds he has the means to cultivate an Om uprising.

“[Fantastic Planet] is a completely thought-through science-fiction vision, ranking alongside Metropolis, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, Dune, Akira, and The Fifth Element, most of which were made many years later, and all of them on far greater budgets.”

– Michael Brooke, “Fantastic Planet: Gambous Amalga”

Talkin’ bout a revolution

The knowledge device that Terr acquires via a sentimental female Traag named Tiwa, is a strange telepathic headset that reveals to the Om knowledge that he’s unable to process but it also allows him to elucidate and unriddle information about an impending culling of Oms. This “de-Om” happens every so often to strategically regulate the Om population.

As Terr takes action and the Traags counter his insurgency, Fantastic Planet brilliantly emanates innumerable allegorical themes and spirals into visionary genocidal imagery and luminous yet laborious sequences of straight up nightmare fuel.

The emblematic messages are ripe for the choosing; phraseology propaganda, political intolerance, ethnic cleansing, might makes right, even demonizing the quiet comforts of getting stoned. For such an ambitious and hallucinatory head trip it’s amazing that, from behind the Iron Curtain, emerged such discerning psychedelia.

“René Laloux is an artist outside of time.”

– Mœbius

Prometheus Rising

Initiated in Prague but, due to political pressures, moved to and completed in Paris, Fantastic Planet perhaps works best as a Prometheus-like tale expressing the need for individuality. Laloux’s vision of a Dalí-meets-Yellow Submarine alien outlook helps it maintain what still feels like a modern, albeit nostalgic, stoner edge.

The prog-rock meets psychedelic jazz score by Alain Goraguer, which has been sampled steadily and with respect from the hip-hop community, gives the film more street cred (though truly it was never lacking such distinctions). Perhaps the greatest strengths for the film lie in the melding of Topor’s outlandish designs, which work so well with character designer Josef Kábrt and background designer Josef Váňa’s bizarre, beautiful, and bold conceptions.

Like the art itself, what unfolds on this alien world often seems hyper-real and also, at times, entirely unreal. But this strange cosmology is invariably consistent with the exhilarated vision of Laloux and Topor. And what a graceful, jarring, and genuinely weird fairytale vision it is.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.