6. Samson and Delilah (2009, Warwick Thornton)

Australian cinema has a poor history in regards to representations of Indigenous Australians. While Indigenous Australians certainly had a presence during the renaissance of Australian film in the 1970s and 1980s, their roles were generally stereotypical – the savage tribesman, the tracker or the mystic figure of the land.

The homogenous Australia that was presented during the New Wave became far more diverse in the 1990s before a return to landscape cinema was achieved in the early 2000s with a string of Indigenous themed narratives such as Rabbit Proof Fence, Australian Rules, The Tracker and Yolngu Boy.

This prolificacy has continued with more recent films like Ten Canoes and Samson and Delilah, a film which won director Warwick Thornton the prestigious Camera d’Or for best first feature film at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival.

The narrative concerns two teenagers who escape their small community by stealing a car and travelling to Alice Springs, where they are confronted with a bigger, darker world.

A love story that has a harsh sentimentality, it is perhaps the most moving film on this list. The authenticity of the performances and the depiction of the world they inhabit are quite unnerving, as the movie has an intensely bleak view of what Australia is. It is an important film that deserves a larger profile.

7. Animal Kingdom (2010, David Michod)

David Michod’s directorial debut, 2010’s Animal Kingdom, is one of the finest thrillers to come out of Australian cinema. The crime-family drama is a story that has been told before in Australian cinema, with previous films like The Boys and the previously listed Chopper both benefiting from a post-New Wave refusal to glamorise Australia or Australians on screen.

Animal Kingdom rises above these two films however, with a tightly packed script and one of the finest casts ever assembled in an Australian film. Newcomer James Frecheville, the film’s innocent protagonist, becomes embroiled in his uncle’s criminal activity following the death of his mother in the film’s opening.

While the film has been labelled the ‘Australian Goodfellas’, it remains much more low-key. Rather than relying on blood-soaked shootouts, the tension stems from the relationships between family members, with Ben Mendelsohn’s Pope in particular forcing unease in the audience with each muttered line. Alongside Mendelsohn’s menacing performance are strong turns from Australian heavyweights Guy Pearce and Joel Edgerton, while Sullivan Stapleton and Luke Ford are impressive in supporting roles.

At the head of the family and the true highlight of the film however, is Jacki Weaver’s Smurf, the loving but conniving mother to the family of criminals. Weaver is truly frightening as the seemingly docile maternal figure, a person who would and does do anything to protect her boys. The performance attracted a host of awards and nominations, including an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, marking Animal Kingdom as the first Australian film to receive an acting nomination since Shine in 1996.

8. Predestination (2014, Spierig brothers)

Unfortunately for some, Australian film rarely enters into genre territory, and when it does we get social realist-tinged horror films like Snowtown and The Babadook. While these films represent some of the highlights of Australian cinema in the 21st century, they still bare a strong resemblance to the Australia’s dominant cinematic style, a style that can become dull and saturated. However, in the form of 2014’s Predestination, the Aussie screen received welcome relief.

Predestination is directed by the Spierig brothers, two brothers who announced themselves in 2003 via a minuscule-budgeted zombie-comedy titled Undead. The film saw a noteworthy amount of success on international home video, allowing the brothers a significant budget to direct 2009’s Daybreakers, a vampire film that was a coproduction between Screen Australia and Lionsgate, before finally directing Predestination in 2014.

A twisty, thought provoking time-travelling adaptation of Robert A. Henlein’s short story, All You Zombies, Predestination is at times deliberately slow, trickling through moment of clarity and comprehension before revealing one of the more ambitious finales of 2014. The film will leave you itching for a repeat viewing to understand what the hell just happened, or simply to marvel at the intersex performance of Sarah Snook, a role that was unfortunately forgotten in awards season.

9. The Babadook (2014, Jennifer Kent)

Jennifer Kent’s directorial debut, The Babadook, was one of the most critically acclaimed films of 2014, and possibly the finest Australian horror film since Wolf Creek.

The film has a rather typical premise, that of a mother and her son being threatened by a creature from beyond this world, a simplicity that is quickly eroded in the film’s opening act. Director Jennifer Kent hastily subverts the genre conventions that accompany these types of the film in the opening act, in which the film explores themes typical of social realism, such as class and familial drama, or more precisely, motherhood.

Aside from a few sparing moments in which The Babadook enters true horror territory, courtesy of the terrifying and possibly metaphoric Babadook creature, the film is more concerned with psychological drama. The film’s protagonist, Amelia, played by Essie Davis in one of 2014’s most accomplished performances, resents her son. This is set up through the film’s opening, in which Amelia’s husband is killed in a car crash while the couple are rushing to the hospital to give birth to their son, Samuel.

This creates a tension between mother and son, as the haunting memory of Amelia’s husband conflicts with the birth of Samuel, ostensibly positing Samuel as the embodiment of her inner suffering. This is where the true horror of the film lies, as when Kent depicts this relationship of maternal anguish, she is able to realistically detail how a mother could feel a lack of love for her own son, a quite troubling notion.

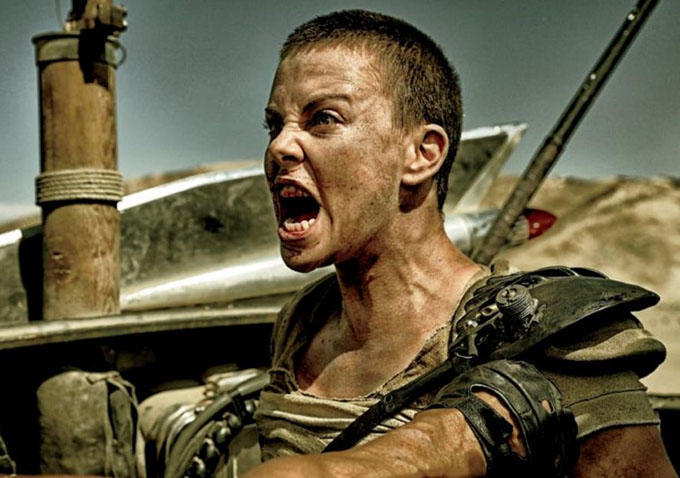

10. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015, George Miller)

Mad Max: Fury Road had been stuck in “development hell” since the release of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, with pre-production for a fourth film in the franchise beginning as early as 1997. For reasons as varied as the September 11 attacks, the Iraq War, Mel Gibson’s unsavoury behaviour and security reasons related in attempting to film in Namibia, the film stalled. Finally in 2012, principal photography began in Namibia, a late replacement for Victoria’s Broken Hill after an unprecedented amount of rain flowered the region.

In place of Australia’s action icon Mel Gibson as the eponymous Mad Max stood Tom Hardy, keeping the character young and positioning the film as more of a spiritual sequel than one with direct lineage to the previous films.

George Miller stated during pre-production that visuals would be the priority, with relatively little dialogue, and the end-product certainly adheres to the vision. The film is essentially two straight hours of some of the most pulsating and inventive action ever seen on the screen, Australian or not. Fury Road is a showcase of the practical genius that is George Miller, whose previous film was Happy Feet Two, a fact which offers some insight into the mindset of one the craziest men working in Hollywood.

The two-hour long car chase that is the film never feels tired, as each spectacular set-piece brings a new breed of marauder, a frightening new car design or a setting that belongs in another universe. In reducing Fury Road to a simple action film would be to do a disservice to the film though, as while action cinema tends to blunt the viewer’s emotive output, Fury Road’s narrative accompanies the visceral action in its attentiveness.

In creating a narrative that concerns returning female agency, Miller has made an action film in which we actually care about the wider cast, rather than simply enjoying our action heroes swiftly cut down foe after foe (which is also pretty great).

Fury Road received a stunning amount of critical attention, featuring on the top ten lists on the likes of The New York Times, The American Film Institute and Cahiers du Cinema.

Honorable Mentions: Kokoda, Gettin’ Square, Little Fish, Snowtown, Lantana, Van Diemen’s Land, The Home Song Stories, Rogue.

Author Bio: Ned is a recent graduate of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. He completed his thesis in his final year of study, in which he focused on realism in Australian cinema, but he is also a massive horror buff and lover of independent cinema. Ned plans on undertaking a PhD in 2017.