The libertarian political belief, has historically not been a popular ideology within the largely left-wing factions of mainstream Hollywood. Yet this seemingly right-wing political theory bears major ambiguities regarding its origin within the political spectrum, particularly through its similarities with Anarchism, believing that government control should be minimal and that the onus of control should be left upon the individual.

The urge of Libertarianism to highlight the autonomy of the individual will, leads to its manufacturing of bold and independent characters, who often stand out against the mass control of government despots and all other forms of conformity.

This is exactly why libertarian ideology is masterful in creating fascinating protagonists within film, whose adverse nature to the normative force of the general will functions in creating the harrowing conflict of the minority against a majority.

1. The Fountainhead (1949)

Vidor’s ‘The Fountainhead’ dispels a story surrounding the enigmatic Howard Roark, a man who is kicked out of architecture school due to his inabilities to conform to their ideals.

Roark subsequently commences a journey of self-dependence and determination, in which his strict self-reliant policy towards the standards of his work and choices results in his working in intensive labouring to support himself, regarding it as the only honest work.

Within the steel mill, Roark capture the attention of Dominique Francon (Patricia Neal), the beautiful daughter of a powerful billionaire, who attempts to break his steel-like tenacity and falls in love with him as a result of failing to do so.

The idealisation of Ayn Rand’s character Howard Roark in King Vidor’s 1949 film version of ‘The Fountainhead’, depicts a protagonist clearly pit in opposition to the rest of the world. However, what is made most striking about Howard Roark is his impenetrable strength against the burden of any mainstream force and control.

Gary Cooper’s depiction of Roark, as an ideal of rigorous human individuality and independence, creates a seemingly inhuman or unrealistic character that stands more as a symbol of Rand’s ideals as opposed to being a reflection of the real world. His unavowing ideals against the pressures of conformity that are specifically imposed upon him, demonstrate the rarity of true character and self-acceptance within the commercial and manufactured nature of the modern world.

The further anxiety inflicted upon the characters, that are unable to break Roark into their mould of humanity, demonstrates the highly uncomfortable truth, in which we may very well live in a world that does not truly appreciate true individualism, yet is rather threatened by anything that stands to contest with the status quo of our society.

2. 1984 (1984)

‘1984’ follows the story of Winston Smith (John Hurt), who possesses the secret notion that everything with his world underneath the all-seeing eye of big brother is not quite right. It is not until he forms a clandestine relationship with his co-worker Julia (Suzanna Hamilton) that his feelings are confirmed within someone else, and as a result begin to develop.

Michael Radford’s film version of the classic Orwell novel ‘1984’, utilises a dystopia of totalitarianism, in order to fight against the ideals of the various ‘isms’ that began to plague the political platform of the early twentieth century.

From German Nazism within the Fascism of WWII to the break of Communism in Russia, Orwell antagonises both extremist political ideologies within their resultant forms of totalitarian government structures. While ‘1984’, is not popularly viewed as a libertarian film, it is its particular forewarning against the centralisation of government control, which lends itself to the notion of minimising the potential of a nanny state.

The ideals conveyed within ‘1984’, pushes away from conformity, in which the individual is crushed. The film seems to suggest that if John Hurt’s Winston was allowed to live in a society that celebrated individual thought, and stamped out forms of excessive government control, we would not only not be much happier, yet much safer from becoming a totalitarian state.

3. V for Vendetta (2005)

James McTeigue’s ‘V for Vendetta’ shares similar aspects to ‘1984’ through its forewarning of increasing government control. John Hurt’s reappearance in this tale of totalitarianism further echoes his portrayal of Winston Smith in the Orwellian classic. However, on this side of the coin he plays the ‘big brother’-type figure in the character John Sutler.

What sets this film apart from its predecessor is the bold characters that it erects from the shadows of the totalitarian dystopia it depicts.

The boldly individual and heroic characters Evey (Natalie Portman) and V (Hugo Weaving), who wreak havoc against the omnipotent government control, enable the construction of rigorously libertarian ideals. Their stark individualism against the grain of societal submissiveness and their cemented beliefs in social independence makes them champions to various libertarian ideals.

The brutalities that result from the construction of an all-powerful and pervasive government are further portrayed as on the verge of genocidal, ringing back to the Orwellian fears of German Nazism and all forms of totalitarianism.

4. Meet John Doe (1941)

Frank Capra is renowned for his ability to construct bold and resilient characters that often stand up against the morally corrupted forces. Capra’s ‘Meet Jon Doe’ is no stranger from this trope, relaying the story of John Doe (Gary Cooper) who declares that he will kill himself as a protest against humanity himself.

The catch is, this supposed Jon Doe is really a phony, who fills the place of a fictitious character conjured by columnist Ann Mitchell (Barbara Stanwyck). However, it is his feigned misanthropy for the status quo of society, which bolsters a frenzy of political fervour and revolutionary spirit.

Despite the inauthentic origins of this constructed Jon Doe, the film expresses the importance of individualism at its very heart. The strength of the minority in changing the world is expressed through the use of the everyday male figure in ‘John Doe’, whilst the subsequent issues that culminate within aphorism, “beware of false prophets”, becomes the film’s secondary and perhaps more important message.

Whilst there is the strength of the individual in inciting change, the film expresses a concern for collectivist ideologies, which are incited by John Doe’s conspirers who coax him into spouting fascist propaganda.

Libertarianism prevails through its deconstruction of ‘the mob’, which Capra points to as problematic through its unthinking and hysterical tendencies. It is shown through the pathos of Gary Cooper’s character, that is only when the individual themselves can engage critically and independently with their societal plight can could change be truly evoked.

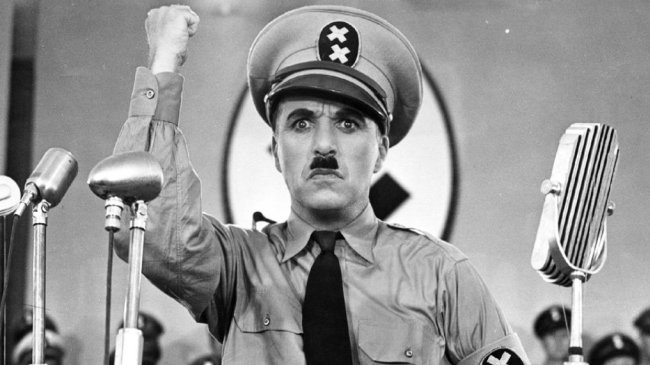

5. The Great Dictator (1940)

A truly remarkable film, written, directed and starring the force of nature that was Charlie Chaplin, ‘The Great Dictator’ spins a compelling satire of the Nazi forces currently active at the time in Germany.

Chaplin plays a Jewish Barber who gets confused for the dictator named Adenoid Hynkel. Initially shocked with awe by the effect of the party in its anti-Semitic policies, he joins the causes of the rebellious forces, in which he meets the beautiful Hannah (Paulette Goddard).

The otherwise farcical qualities to most famously comedic canonical works of Chaplin, the culminating speech of ‘The Great Dictator’, espouses a policy of love, in which dogmas of nationalism and fascism are condemned for their lack of humanity. If not able to watch this film in its entirety, at the very least, this speech is a must-see.

It evokes a simple notion of universal love and happiness, promoted through a utilitarian means. Despite some potentially perceiving this speech as socialist within its use of terms such as “the brotherhood of man”, it still however rejects this notion of ‘brotherhood’ as a national-based identifier, rather attributing this brotherhood as universal and world-wide inclusion.

Thus, it is the large scale of individual respect and love espoused in this speech, in which the libertarian notion of optimising the happiness of each individual comes through. Therefore, it is not only politically aligned with this philosophy through his rejection of Nazi-fascism, yet further through its rejection of nation-based identity in exchange for individual personhood.